Informazione

AUDIZIONI ALLA COMMISSIONE ESTERI DEL PARLAMENTO CANADESE -

SECONDA PARTE

In un precedente messaggio

( http://www.egroups.com/group/crj-mailinglist/79.html? )

abbiamo riportato alcune delle audizioni tenute ad Ottawa, alla Camera

dei Comuni, dinanzi allo Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and

International Trade da parte di varie personalita' ritenute a vario

titolo "informate sui fatti" riguardo alla aggressione della NATO contro

la Repubblica Federale di Jugoslavia.

Continuiamo ora con la seconda parte del contributo di SERGE TRIFKOVIC,

professore di storia, responsabile per gli esteri di "Chronicles -

Magazine of American Culture", e con il contributo di MICHAEL MANDEL,

professore di diritto alla Osgoode Hall Law School, York University,

Toronto, che insieme ad altri avvocati ha presentato denuncia contro la

NATO al Tribunale dell'Aia per i crimini commessi sul territorio della

ex-RFSJ. La denuncia giace, tuttora "insabbiata", in qualche cassetto di

Carla dal Ponte.

Tutti i documenti sono stati diffusi dalla lista stopnat-@...

------- Forwarded Message Follows -------

Date sent: Thu, 24 Feb 2000 16:00:58 -0500

From: "minja m." <minja@...>

Send reply to: minja@...

To: KPAJ 3A HATO <kpaj-3a-hato@...>

Subject: Srdja Trifkovic in Ottawa House of Commons - Pt.

2

Trifkovic in Ottawa House of Commons - Pt. 2

HOUSE OF COMMONS - CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES

STANDING COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND INTERNATIONAL

TRADE -

COMITE PERMANENT DES AFFAIRES ETRANGERES ET DU

COMMERCE INTERNATIONAL

UNEDITED COPY - COPIE NON EDITEE

• 0927 EVIDENCE

[Recorded by Electronic Apparatus]

Ottawa, Thursday, February 17, 2000

[English]

The Chairman (Mr. Bill Graham (Toronto Centre-Rosedale, Lib.)):

Colleagues, I'm going to call this meeting to order. So I'll ask the

people at the back of the room if they're going to have conversations to

go outside. I'm going to ask Ms. Swann from the Ottawa Serbian Heritage

Society if She could go first. Then we'll put Mr. Trifkovic. Mr. Dyer

hasn't arrived yet. I just want to warn everybody it may be a bit

chaotic

this morning. I'm not saying it isn't always chaotic but it may be more

chaotic than usual because we may be called for votes and this happened

the last time. So I apologize to the witnesses first if we're called out

of the room for votes. It just seems to be a bit- The House seems dans

un

peu de perturbation comme on dirait peut-être dans la langue française,

n'est-ce pas, and so we'll just have to deal with that if it occurs.

Otherwise we'll go on. But I'd ask the witnesses if you keep yourself To

10 minutes each and then we'll move to questions. [...] Mr. Trifkovic...

Mr. Serge Trifkovic (Individual Presentation): [... Text of presentation

as previously distributed... Transcript of ensuing Q&A follows herewith]

The Chairman: Thank you, sir. [... A member asked if it was preferable

to

have a world court to deal with human rights violations, or ad-hoc

tribunals for individual crisis areas...]

Ms. Serge Trifkovic: I was somewhat puzzled by the clear-cut choice

between the WCC [World Criminal Court] and ad hoc tribunals as the only

alternatives we are facing. To me it sounds a bit like the choice

between

cancer and leukemia. I do not believe that bureaucratically structured

and

politically motivated international quasi-judicial bodies are either

desirable or feasible. In any proper sense a "tribunal" is an impartial

forum for administration of justice. If the kangaroo court that goes by

the name of The Hague Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia is any indicator, I

think the lesson of that particular body is that its model of justice is

Moscow 1938, and not Nuremberg in 1946. It was formed on a purely

political agenda by the Security Council, on the basis of Chapter 7. The

way it has acted, in terms of its procedures, its rule of evidence and

finally the selection of people to be indicted and prosecuted - and also

its refusal to indict and prosecute people who at prima facie should be,

such as the leaders of the 19 NATO countries -only indicates that it is

a

political body par excellence. There is no reason at all why a WCC would

be any different because, obviously, if you have the likes of Clinton

and

Blair deciding what is "necessary" and "feasible" in terms of

intervention, ultimately they would be deciding what is "necessary" and

"feasible" in terms of prosecution. The kind of political discipline in

the world that this would impose is eerily reminiscent of the Brave New

World of Huxley or "1984." I suspect that bodies such as the ones that

you

are mentioning will only take us a step further in the direction of

global totalitarianism in which the local and national traditions of law

and justice and jurisprudence- which are meaningful because they have

evolved within the context of a genuine, authentic national culture-

will

be replaced by something that is global, something that is allegedly

universal and, therefore, of necessity, ideological.

The Chair: Okay. I'm sorry, we're going to have to move on. It's a very

fascinating discussion. • 1025 [English] I've got to leave with with the

thought that you've always got to answer alternatives so I'll come to

you

and ask "What's your alternative". My alternative is that there's going

to

be United States imperial courts applying their jurisdiction around the

world to enforce it, so that may be worse for you. Anyway, that's just-

Mr. Serge Trifkovic: My alternative is to rediscover the beauty of a

society of nations in which enlightened national interests, based upon

the

Golden Rule of "I will not deny to anyone what I am asking for myself",

will be the basis of law and the basis of international relations. I am

not claiming that it was a long-lost golden age in Europe between

1815-1914, that we ought to yearn for in terms of reactionary nostalgia.

I'm simply saying that what we are offered as a replacement in the

Blairites' and Clintonistas' brave new world is infinitely worse and

infinitely more frightening.

Mr. Chuck Strahl: Well, you asked.

The Chair: I asked, and that may be.We're going to go to Ms. Augustine

and

then we're going back to Mr. Strahl and Mr. Robinson.

Ms. Jean Augustine (Etobicoke-Lakeshore, Lib.): Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

[...]

I am grappling with what is the future of Kosovo, is it going to be an

international protectorate? Is it going to be an entity no longer linked

[to Serbia-Yugoslavia]? [...]

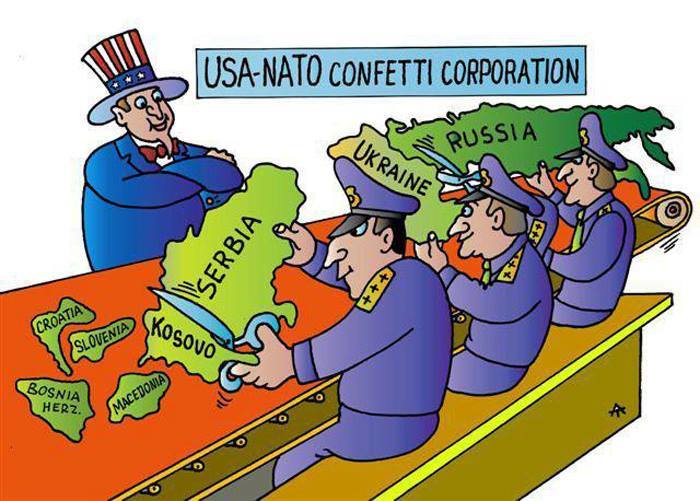

Mr. Serge Trifkovic: I would like to make a few comments about the

future because we keep forgetting the broad picture, what will happen in

the long term. The Kosovo crisis is primarily the result of the U.S.

involvement In the Kosovo situation. Until the moment Dick Holbrooke

decided that this was something they would tackle in a big way, it was -

I

insist - a low-level, unremarkable conflict, the likes of which we see

all

over the world, all of the time. At the moment there is a whole series

of

geopolitical reasons why the Washington administration wants to be

involved in the Balkans. I'm afraid we have no time to go into those in

any detail. But the important thing for the members of this Committee to

remember is that you shouldn't take the "humanitarian" and other alibis

as

face value. You should always assume that there is an agenda behind it.

One of them is to have a U.S. foothold in the European mainland that

will

not be subject to the ups-and-downs of the trans-Atlantic relationship,

so

that if and when the Germans, the French and others decide to create a

European Defence structure that will gradually detach West Europeans

from

NATO, which will ultimately lead to the closure of U.S. bases in Naples

and in Frankfurt and in Munich, there will be the assets in Skopje, and

in

Pristina, and in Tuzla, that will provide both the physical and the

political and military U.S. presence that will not be affected by such a

change in the relationship. When I say there are geopolitical reasons

which have a logic of their own, I am not claiming that in this

particular

case we can establish a definite sequence of events. • 1105 [English]

I'm

simply saying that humanitarian and moralistic claims by themselves are

neither a sufficient nor necessary explanation. In order to look at

Kosovo

in the longer term we have to ask the question: what will happen if and

when the United States administration after Clinton, or even after

whoever

comes after Clinton, loses interest in the Balkans? At the moment

they're

creating the demand for their involvement by creating a whole series of

small, fragmented and unviable units that, by themselves, have neither

the

political, nor cultural, nor historic meaning - such as Dayton-Bosnia,

such as Kosovo, such as, tomorrow maybe, Sanjak or Montenegro, Vojvodina

or whatever. If and when the presence of the underwriters in the Balkans

are removed, we will have another bout of Hobbesian free-for-all. And

that

is the tragedy of it all, because what is being done right now is not

the

foundation for a solid, just and durable peace, but just an

improvization

on an ad-hoc basis. It bears no relation to history, no relation to the

continuity of the political and cultural development in that part of

the

world, but satisfies the needs of the moment. I'm saying this not as

someone born in Serbia, but someone who is trying to look at the

political

essence of the problem - that so far the U.S. administration has

followed

the principle that all of the ethnic groups in the area can be satisfied

at the expense of the Serbs. The result is a sort of Carthaginian peace

imposed upon the Serbian nation that will create a constant source of

revanchist resentment among the Serbs, and determination to turn the

tables once Uncle Sam loses interest. I feel that there will be a war

again: the Serbs will fight to return Kosovo to their own rule, because

they feel Kosovo to have been unjustly detached. And so, whatever

scenario

the people in Brussels, London, Washington, Ottawa, or Bonn decide for

Kosovo today, it will not be worth the paper it's written on if it

doesn't

bear any relation to the geopolitical realities in the long term, and

those realities are fairly simple. You will not be able to impose

something called "multicultural" Kosovo, "multi-ethnic" Kosovo if people

on the ground - and I have primarily the Albanians in mind - are

determined to have a mono-ethnic Kosovo. By including 25% Serbian

members

in any quasi-representative bodies you introduce, you will not re-invent

a

"multi-ethnic Kosovo" in which grannies are able to return to their

apartments. At the moment the only way people in Kosovo will feel safe

and

secure living in their communities is if you have a de facto petition.

Whether it is accompanied by a constitutional and political model that

will sanctify that partition is neither here nor there. But in the long

term you have to realize that an imposed "peace" on the Serb nation that

does not take into account the legitimate interests of the Serbs, that

does not take into account the sort of give and take in which each party

will feel that it has lost something as well as gained something, will

be

unviable, will be unjust, and will be - in the long term - the source of

another conflict.

The Chairman: Okay. [...]

Mr. Chuck Strahl: I'm going to pass to Mr. Robinson, but before I do, I

understand, Prof Trifkovic, you must leave shortly to catch a plane to

Europe- Mr. Serge Trifkovic: Actually, to Chicago- Mr. Chuck Strahl: To

Chicago. Mr. Serge Trifkovic: -and change to the plane for Amsterdam.

Mr.

Chuck Strahl: Right. Mr. Serge Trifkovic: I can stay for another 10

minutes. Mr. Chuck Strahl: Okay. When you're comfortable to leave just

leave. I want to say, then if you just do get up and go- Mr. Serge

Trifkovic: There will be no tears shed. Mr. Chuck Strahl: No. There will

be tears. They may be crocodile. They may be joy, who knows? But

certainly

I just want to say we appreciate very much you taking the time to come.

There's no doubt about it being a very interesting intervention. Please,

when you have to go, just feel free to get up and go and don't think us

rude if we don't properly acknowledge your very important contribution.

Thank you, sir. Mr. Robinson. Mr. Svend Robinson: I'm afraid I'll have

to

leave around the same time. I'm not sure if the tears will be quite as

intense, but- The Chair: If the tears are shed- Some hon. members: Ha,

ha.

The Chair: Mr. Robinson, the tears are shed when you arrive, not when

you

leave.

Mr. Svend Robinson: I just had two questions, I guess for Mr. Trifkovic

and Ms. Swann, in particular. First, I wonder if you could just perhaps

elaborate a bit on some of the concerns around the current situation in

Pancevo and what your knowledge is of the situation in Pancevo. I had

the

opportunity to visit there and

The situation had the potential of being an environmental disaster. I'm

just wondering what the current analysis is of the outcome of the

bombing

in that area and what sort of testing has been done, for example, of the

environment, the water, the air and so on. Because there were serious

concerns about that. My second question, again to both of you. I wonder

if

you could talk a little bit about • 1120 [English] about the

responsibility of Serbs in Kosovo for wrongdoing. The United Nations

High

Commission on Refugees documented quite powerfully a major exodus of

Kosovar Albanians before March 24. I'm sure you're familiar with those

reports. You've seen those reports. Figures as many as 90,000 who had

left

their homes, left their villages. After the bombing started, did the

bombing exacerbate the flow of people. I have no doubt that it did.

Certainly a number of people who I spoke with pointed out how in some

cases Serbs on the ground were pointing up into the sky and saying you

were responsible for NATO. They felt that they were under siege from the

KLA, the NATO bombs and obviously when people are defenceless on the

ground they're totally vulnerable. It was a coward's war in many

respects,

but nevertheless people were driven out in huge numbers. Hundreds of

thousands of people left and were driven out. I was on a road from

Pristina down to the border with Macedonia, went through village after

village which were like ghost towns, houses had been burned to the

ground

in many cases and there's culpability for that and I want to hear from

you, both of you, some acknowledgement that yes we have to deal with

this

as well as part of the reckoning that must come out of this tragic

series

of events.

Mr. Serge Trifkovic: I'll deal with the second one and then I'll have to

go. I think the important thing to bear in mind in the Balkans is there

are no white hats and black hats and that's the fundamental problem that

we have faced with the coverage of the war in the media, and with

quasi-academic analysis, and with political decision-making. Very early

on

in this conflict an overall perception of the culpability of the Serbs

for

the Krajina, Bosnia and Kosovo was created even though very often the

reasons the Serbs reacted in the Krajina are very similar to the reasons

the Albanians reacted in Kosovo and vice versa. In some cases, the Serbs

were de facto separatists, wanting to secede from the separating entity.

In other times, they were the unitarists. In both cases they were deemed

wrong. But if you try to quantify the evil on all sides, it's impossible

to say that the Serbs proved qualitatively, fundamentally worse than

other

groups. Right now the Serbs constitute the largest refugee population

outside sub-Saharan Africa. To say that the Serbs have done evil things

is

almost a truism because in the Balkan imbroglio all sides have done very

evil things. If you want the Serbs to beat their chests and shout mea

culpa, well indeed, maybe they should because the Patriarch warned them

against

adopting some of the techniques and some of the feelings of their

enemies as they experienced them in 1941 to 1945 in the so-called

independent state of Croatia. [...] If this was the war to return the

Albanians, or in the memorable words of the then-British defence

minister

"Serbs out, Albanians back, NATO in", nobody is talking about "Serbs

back"

in Kosovo these days... a quarter of a million displaced Serbs and other

non-Albanians under NATO, in the aftermath of NATO's victory. So I will

be

the first to admit that the Serbs have done bad things just as everybody

else has done bad things; but it doesn't mean we are now going to ask

the

question how deserving are the Croats of being bombed • 1125 [English]

because they contributed "collectively" to the exodus of a quarter of a

million Serbs from the Krajina? How deserving are the Muslims of

castigation and bombing because right now, the whole of Sarajevo-until

1991, the second largest Serbian town after Belgrade - is Serbenfrei?.

If

we are to re-establish a modicum of reality in this debate, we have to

bear in mind that human fallibility and human culpability is not the

exclusive prerogative of anyone single ethnic group. Thank you.

Mr. Svend J. Robinson: Mr. Dyer, were you wanting to comment?

Mr. Gwynn Dyer: I was particularly struck by the use of the word

"Serbenfrei" to describe the Serbian authorities' removal of the Serbian

population of Sarajevo after the Dayton Accords. There were Serbians in

that city who were driven from their homes by the Serbian police. I was

there; I saw it. The idea that the Albanian Muslims and the Bosnian

Muslims and the Croats bear equal responsibility-all of them have done

bad

things. Of course bad things happen in war but neither the total of

refugees nor the total of dead nor the evidence of massacre suggests in

any way that there is shared responsibility equally indistinguishably

among the ethnic groups of the Balkans. Now this may be to some extent

because the Serbs inherited the heavy weapons of the Yugoslav army and

had

the ability to do more damage; I recognize that. The Bosnian Muslims

didn't have heavy artillery to shell Serbian villages as the Serbs did

to

shell Sarajevo. But I do find the line of argument which suggests that

there can be no distinguished distinction between Vukovar and Srebrenica

on the one hand, and the Krajina on the other hand. The Krajina Mark Two

-

when it was the Serbs who lost their homes - rather Mark One, when it

was

the Croatian inhabitants who were driven. I think is a travesty.

Mr. Serge Trifkovic: To claim that the Krajina is less of a crime than

"Srebrenica," even though the Krajina resulted in between 9 thousand and

12 thousand Serbian deaths, is a very curious argument, both morally and

intellectually. But in particular, I find it reprehensible that Kosovo

is

still referred to as a "massacre" because "the Kosovo massacre" is one

of

the biggest lies, media-mediated political lies of the decade, if not

the

century. In perspective, when a few decades pass, it will belong to the

same category as the bayonetted Belgian babies by the Kaiser's army in

1914. [...]

----

House of Commons-Canada

Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade

Tuesday February 22, 2000

Testimony of Professor Michael Mandel

Personal Note

Allow me to tell you a little bit about myself and how I became involved

in this. I am a professor of law at Osgoode Hall Law School where I have

taught for 25 years. I specialize in criminal law and comparative

constitutional law with an emphasis on domestic and foreign tribunals,

including United Nations tribunals such as the International Criminal

Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. I have no personal interest in the

conflict in Yugoslavia – I have no Serbs or Albanians in my family and I

am not being paid by anyone. I became involved in this as a Canadian

lawyer who witnessed a flagrant violation of the law by my government

with unspeakably tragic results for innocent people of all the Yugoslav

ethnicities. I became involved as a Jew appalled by the grotesque and

deliberate misuse of the Holocaust to justify the killing and maiming of

innocent people for what I am convinced were purely self-interested

motives, the farthest thing from humanitarianism, in a cynical attempt

to manipulate the desire of Canadians to help their fellows on the other

side of the world.

Illegality of the War

The first thing to note about NATO's war against Yugoslavia is that it

was flatly illegal both in the fact that it was ever undertaken and in

the way it was carried out. It was a gross and deliberate violation of

international law and the Charter of the United Nations. The Charter

authorizes the use of force in only two situations: self-defence or when

authorized by the Security Council.

The United Nations Charter provides in so far as is relevant:

Article 2

3. All Members shall settle their international disputes by peaceful

means in such a manner that international peace and security, and

justice, are not endangered.

4. All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the

threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political

independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the

Purposes of the United Nations.

Article 33

The parties to any dispute, the continuance of which is likely to

endanger the maintenance of international peace and security, shall,

first of all, seek a solution by negotiation, enquiry, mediation,

conciliation, arbitration, judicial settlement, resort to regional

agencies or arrangements, or other peaceful means of their own choice.

Article 37

1. Should the parties to a dispute of the nature referred to in Article

33 fail to settle it by the means indicated in that Article, they shall

refer it to the Security Council.

2. If the Security Council deems that the continuance of the dispute is

in fact likely to endanger the maintenance of international peace and

security, it shall decide whether to take action under Article 36 or to

recommend such terms of settlement as it may consider appropriate.

Article 39

The Security Council shall determine the existence of any threat to the

peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression and shall make

recommendations, or decide what measures shall be taken in accordance

with Articles 41 and 42, to maintain or restore international peace and

security.

Article 41

The Security Council may decide what measures not involving the use of

armed force are to be employed to give effect to its decisions, and it

may call upon the Members of the United Nations to apply such measures.

These may include complete or partial interruption of economic relations

and of rail, sea, air, postal, telegraphic, radio, and other means of

communication, and the severance of diplomatic relations.

Article 42

Should the Security Council consider that measures provided for in

Article 41 would be inadequate or have proved to be inadequate, it may

take such action by air, sea, or land forces as may be necessary to

maintain or restore international peace and security. Such action may

include demonstrations, blockade, and other operations by air, sea, or

land forces of Members of the United Nations.

Article51

Nothing in the present Charter shall impair the inherent right of

individual or collective self-defence if an armed attack occurs against

a Member of the United Nations, until the Security Council has taken

measures necessary to maintain international peace and security.

Measures taken by Members in the exercise of this right of self-defence

shall be immediately reported to the Security Council and shall not in

any way affect the authority and responsibility of the Security Council

under the present Charter to take at any time such action as it deems

necessary in order to maintain or restore international peace and

security;

The jurisprudence of the International Court of Justice is also clear.

For instance, it stated in its ruling against United States intervention

in Nicaragua:

In any event, while the United States might form its own appraisal of

the situation as to respect for human rights in Nicaragua, the use of

force could not be the appropriate method to monitor or ensure such

respect. With regard to the steps actually taken, the protection of

human rights, a strictly humanitarian objective, cannot be compatible

with the mining of ports, the destruction of oil installations, or again

with the training, arming and equipping of the contras.

[CASE CONCERNING THE MILITARY AND PARAMILITARY ACTIVITIES IN AND AGAINST

NICARAGUA (NICARAGUA v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA) (MERITS) Judgment of

27 June 1986, I.C.J. Reports, 1986, p.134-135, paragraphs 267 and 268]

It should also be noted that the preliminary decision of the World Court

last year in Yugoslavia's case against 10 NATO countries, including

Canada, does not in the slightest contradict this. As Mr. Matas has

pointed out to you in his statement, this decision was taken on purely

jurisdictional grounds, first the United States' shameful refusal to

recognize the World Court's jurisdiction in general, and second Canada's

objection to jurisdiction in this specific case. But it is worth quoting

some paragraphs from the decision of the Court:

15. Whereas the Court is deeply concerned with the human tragedy, the

loss of life, and the enormous suffering in Kosovo which form the

background of the present dispute, and with the continuing loss of life

and human suffering in all parts of Yugoslavia;

16. Whereas the Court is profoundly concerned with the use of force in

Yugoslavia; whereas under the present circumstances such use raises very

serious issues of international law;

17. Whereas the Court is mindful of the purposes and principles of the

United Nations Charter and of its own responsibilities in the

maintenance of peace and security under the Charter and the Statue of

the court;

18. Whereas the Court deems it necessary to emphasize that all parties

appearing before it must act in conformity with their obligations under

the United Nations Charter and other rules of international law,

including humanitarian law.

[CASE CONCERNING LEGALITY OF USE OF FORCE (YUGOSLAVIA V. CANADA)

International Court of Justice, 2 June 1999]

To sum up, in the case of NATO's war on Yugoslavia, neither of the two

exclusive bases for the use of force (Security Council authorization or

self-defence) was even claimed by NATO.

As a violation of the United Nations Charter, the attack on Yugoslavia

was also a violation of the NATO Treaty itself and Canada's own domestic

law.

The NATO Treaty (1949), so far as is relevant, reads as follows:

[Preamble]: The Parties to this Treaty reaffirm their faith in the

purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations and their

desire to live in peace with all peoples and all governments.

Article 1: The Parties undertake, as set forth in the Charter of the

United Nations, to settle any international dispute in which they may be

involved by peaceful means in such a manner that international peace and

security and justice are not endangered, and to refrain in their

international relations from the threat or use of force in any manner

inconsistent with the purposes of the United Nations.

Article 7: This treaty does not affect, and shall not be interpreted as

affecting in any way the rights and obligations under the Charter of the

Parties which are members of the United Nations, or the primary

responsibility of the Security Council for the maintenance of

international peace and security.

The Canada Defence Act, in so far as relevant reads as follows:

31. (1) The Governor in Council may place the Canadian forces or any

component, unit or other element thereof or any officer or

non-commissioned member thereof on active service anywhere in or beyond

Canada at any time when it appears advisable to do so

(a) by reason of an emergency, for the defence of Canada; or

(b) in consequence of any action undertaken by Canada under the United

Nations Charter, the North Atlantic treaty or any other similar

instrument for collective defence that may be entered into by Canada.

The war's illegality is not disputed by any legal scholar of repute,

even those who had some sympathy for the war, for instance Mr. Mendes in

his presentation to this Committee. Of course, Mr. Mendes calls this a

"fatal flaw" in the UN Charter. I don't believe it is a flaw at all, for

reasons I'll elaborate. But I don't think the seriousness of this can be

glossed over one bit: the flagrant violation of the law by our

government is no small thing. Democracy is quite simply meaningless if

governments feel they can violate the law with impunity.

Humanitarian Justification

We all know that the leaders of the NATO countries sought to justify

this war as a humanitarian intervention in defence of a vulnerable

population, the Kosovar Albanians, threatened with mass atrocities.

A lot turns on this claim, but not the illegality of the war. In fact,

the reason why there is such unanimity among scholars on the illegality

of this war is that there is no "humanitarian exception" under

international law or the United Nations Charter. That does not mean that

there are no means for the international community to intervene to

prevent or stop humanitarian disasters, even to use force where

necessary. It just means that the use of force for humanitarian purposes

has been totally absorbed in the UN Charter. A state must be able to

demonstrate the humanity of its proposed intervention to the Security

Council, including, of course, the five permanent members possessing a

veto. Nor has the Security Council shown itself to be incapable of

acting in these situations. It issued numerous resolutions authorizing

action in this conflict (Resolutions 1160, 1199, and 1203 of 1998 and

Resolutions 1239 and 1244 of 1999, the last of which brought an end to

the bombing). The Security Council has also shown itself capable of

authorizing the use of force, for example its authorization of "all

necessary means" to restore the sovereignty of Kuwait in Resolution 678

of November 29, 1990, which gave Iraq until January 15, 1991 to

withdraw. Bombing by the Americans commenced on January 16.

But NATO did not even move a Resolution before the Security Council over

Kosovo. Nor did it use the alternative means of demonstrating to the

international community the necessity for its use of force in the

General Assembly's Uniting for Peace Resolution (1950), which allows the

General Assembly recommend action to the Security Council if 2/3 of

those present and voting agree:

[The General Assembly] Resolves that if the Security Council, because of

lack of unanimity of the permanent members, fails to exercise its

primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and

security in any case where there appears to be a threat to the peace,

breach of the peace or act of aggression, the General Assembly shall

consider the matter immediately with a view to making appropriate

recommendations to Members for collective measures, including in the

case of a breach of the peace or act of aggression the use of armed

force when necessary, to maintain or restore international peace and

security."

There are two basic reasons why these procedures were not utilized by

NATO in this case. In the first place, the most plausible explanation of

this whole war was that it was, at its foundation, nothing less than an

attempt by the United States, through NATO, to overthrow the authority

of the United Nations. In the second place, NATO could never have

demonstrated a humanitarian justification for what it was doing, because

it had none.

In law, as in morals, it is not enough for a humanitarian justification

to be claimed, it must also be demonstrated. To use an odious example,

but one which makes the point clearly enough, Hitler himself used a

humanitarian justification for invading Poland and unleashing World War

II: he claimed he was doing it to protect the German minority from

oppression by the Poles.

In the case of NATO, what had to be justified as a humanitarian

intervention was a bombing campaign that, in dropping 25,000 bombs on

Yugoslavia, directly killed between 500 and 1800 civilian children,

women and men of all ethnicities and permanently injured as many others;

a bombing campaign that caused 60 to100 billion dollars worth of damage

to an already impoverished country; a bombing campaign that directly and

indirectly caused a refugee crisis of enormous proportions, with about 1

million fleeing Kosovo during the bombing; a bombing campaign that

indirectly caused the death of thousands more, by provoking the brutal

retaliatory and defensive measures that are inevitable when a war of

this kind and intensity is undertaken, and by giving a free hand to

extremists on both sides to vent their hatred. What also has to be

justified is the ethnic cleansing that has occurred in Kosovo since the

entry of the triumphant KLA, fully backed by NATO's might, which has

seen hundreds of thousands of Serb (and Roma and Jewish) Kosovars driven

out and hundreds murdered, a murder rate that is about 10 times the

Canadian rate per capita.

These results were to be expected and they were predicted by NATO's

military and political advisers in their very careful planning of the

war which went back more than a year before the bombing commenced.

A humanitarian justification would have to show that this disaster was

outweighed by a greater disaster that was about to happen and would have

happened but for this intervention. The evidence for this, which must be

carefully scrutinized by this Committee, is meagre to say the least.

Nobody could seriously maintain that the conditions for a repeat of the

Bosnian bloodbath were there: this was not an all out civil war with

well-armed parties of roughly equal strength on each side and huge

ethnic enclaves fighting for their existence. These conditions simply

did not exist in Kosovo.

Nor did the facts indicate a humanitarian disaster would have occurred

but for NATO's bombing. A total of 2,000 people had been killed on both

sides in the prior two years of fighting between the KLA and the Serbs,

and violence was declining with the presence of UN observers. The

alleged massacre of 45 ethnic Albanians at Racak must be regarded with

the greatest suspicion, not only because of the circumstances, but also

because of involvement of the American emissary Mr. William Walker, with

his history of covert and illegal activities on behalf of the Americans

in Latin America.

Nor is the Report recently released by the OSCE of much value in

assessing the situation, since it was written and paid for by the NATO

countries themselves.

Even more importantly, the evidence is overwhelming that NATO did not

make serious efforts at averting a disaster and was not at all serious

about peace.

If we look at the Rambouillet negotiations, a number of perplexing

questions are raised: Why was the irredentist and insurrectionary KLA

preferred as the NATO interlocutor to the only popularly elected leader,

the moderate Ibrahim Rugova? Why, for that matter was Rugova ignored

during the war? Why did the US insist on a secret annex to the

Rambouillet Accord (Annex B) that would have allowed it to occupy all of

Serbia? Why did the final peace agreement look so much like what the

Serbs had agreed to before the bombing? Do we really think that NATO

could not have put the 10 billion dollars of bombs it dropped to working

out and under-writing a peace agreement that would have accommodated and

protected all sides if it were interested in humanity and not war? Why

are NATO countries so unwilling to spend money on reconstruction of

Kosovo, claiming that they have run out of money with less than one

billion dollars spent?

And where, to resolve these enormous doubts about whether NATO acted out

of humanitarian motives this time, is the evidence that these people

have ever acted from humanitarian motives before? With such huge holes

in its argument, we are entitled to cross-examine the leopard on his

spots. What about the failure to intervene with force in Rwanda? What

about the United States' own bankrolling of the repressive Suharto

regime in Indonesia? What about Turkey's violent repression of the

Kurds, a humanitarian disaster that has claimed 30,000 lives, not 2,000?

What about the United States itself? The richest country in the world

which creates social conditions so violent and racist that its normal

murder rate is in the realm of 20,000 per year, almost as high, per

capita as Kosovo right now - a country that puts 2 or 3 of its own

people to death by lethal injection every week. NATO has no humanitarian

lessons to teach the world.

Finally and very importantly, we must ask some serious questions about

the way in which this supposed humanitarian intervention was handled.

With the Kosovars supposedly in the hands of genocidal maniacs, NATO

gave 5 days warning between the withdrawal of the observers and the

launch of the attack. This was followed by seven days of bombing that

mostly ignored Kosovo itself. In other words, an invitation to genocide

that was not accepted, but one that was guaranteed to produce a refugee

flow to legitimate a massive bombing campaign.

As Ambassador Bissett told this committee last week, that NATO leaders

have no respect for the truth should startle no one. What of the claim

by Jamie Shea that it was the Serbs who bombed the Albanian refugee

convoy (until the independent journalists found bomb fragments "made in

U.S.A.")? What of the claim by a NATO general, with video up on the

screen, that the passenger train on the Grdelica bridge was going too

fast to avoid being hit (until somebody pointed out that the video had

been speeded up to three times its real speed)? What of the claim that

the Chinese Embassy was bombed because NATO's maps were out of date? Let

alone the claims by Mr. Clinton (and Mrs. Clinton) and Mr. Cohen that a

"Holocaust" was occurring in which perhaps 100,000 Kosovar men had been

murdered (until the bombing was over and the numbers dwindled to 2,108 -

and we have yet to be told who they were or how they died).

In fact most people in the world simply did not believe NATO's claim of

humanitarianism. A poll taken in mid-April and published by The

Economist shows that this was a very unpopular war, opposed by perhaps

most of the world's population both outside and inside the NATO

alliance.( "Oh what a lovely war!", The Economist, April 24, 1999

showing more than a third opposed in Canada, Poland, Germany, France and

Finland, almost an even split in Hungary, an even split in Italy and a

majority opposed in the Czech Republic, Russia and Taiwan) A poll taken

in Greece between April 29th and May 5th showed 99.5% against the war,

85% believing NATO's motives to be strategic and not humanitarian, and,

most importantly, 69% in favour of charging Bill Clinton with war

crimes, 35.2% for charging Tony Blair and only 14% for charging Slobodan

Milosevic, not far from the 13% in favour of charging NATO General

Wesley Clark and the 9.6% for charging NATO Secretary General Javier

Solana.( "Majority in Greece wants Clinton tried for war crimes", The

Irish Times, May 27, 1999).

Much more plausible than the humanitarian thesis is the one that the

United States deliberately provoked this war, that it deliberately

exploited and exacerbated another country's tragedy - a tragedy partly

of its own creation (we should not forget that the West's aggressive and

purely selfish economic policies that have beggared Yugoslavia over the

last ten years). NATO exists to make war, not peace. The arms industry

exists to make profits from dropping bombs. And the United States, by

virtue of its military might dominates NATO the way it does not dominate

the United Nations. The most plausible explanation then is that this

attack was not about the Balkans at all. It was an attempt to overthrow

the authority of the United Nations and make NATO, and therefore the

United States, the world's supreme authority, to establish the

"precedent" that NATO politicians have been talking about since the

bombing stopped. To give the United States the free hand that the United

Nations does not, in its conflicts with the Third World and its

rivalries with Russia, China and even Europe.

In other words, this was not a case of the United Nations being an

obstacle to humanitarianism. It was a case of using a flimsy pretext of

humanitarianism to overthrow the United Nations.

Not only was this an illegal war that had no humanitarian justification.

It was a war pursued by illegal means. According to admissions made in

public throughout the war (for instance during NATO briefings),

according to eye-witness reports and according to powerful

circumstantial evidence displayed on the world's television screens

throughout the bombing campaign -- evidence good enough to convict in

any criminal court in the world - these NATO leaders deliberately and

illegally made targets of places and things with only tenuous or slight

military value or no military value at all. Places such as city bridges,

factories, hospitals, marketplaces, downtown and residential

neighbourhoods, and television studios. The same evidence shows that, in

doing this, the NATO leaders aimed to demoralize and break the will of

the people, not to defeat its army.

The American group Human Rights Watch has just issued a lengthy report

documenting a systematic and massive violation of international

humanitarian law by NATO in Yugoslavia. They estimate the civilian

victims to be about 500. This figure should be taken as a minimum

because it is a number Human Rights watch says it can independently

confirm and that can be attributed directly to the bombing. It excludes

persons known to be killed as an indirect result of the bombing. Every

benefit of the doubt is given to NATO, a fact exemplified by the

Report's puzzling and actually undefended distinction between these

grave "violations of humanitarian law" and "war crimes". Human rights

Watch has also documented the use of anti-personnel cluster bombs in

attacks on civilian targets.

The reason these civilian targets are illegal is that civilians are very

likely to be killed or injured when such targets are hit. And all of the

NATO leaders knew that. They were carefully told that by their military

planners. And they still went ahead and did it.

And they did it without any risk to themselves or to their soldiers and

pilots. That's why this war was called a "coward's war". The cowardice

lay in fighting the civilian population and not the military, in bombing

from altitudes so high that the civilians, Serbians, Albanians, Roma,

and anybody else on the ground, bore all the risks of the "inevitable

collateral damage".

War Crimes Charges before the International Tribunal

But the fact that this war was illegal and unjustified has further very

serious implications. Mr. Chretien, Mr. Axworthy and Mr. Eggleton, along

with all the other NATO leaders, planned and executed a bombing campaign

that they knew was illegal and that they knew would cause the death and

permanent injury of thousands of civilian children women and men. Hard

as it is for us to accept, or even to say, killing hundreds or thousands

of civilians knowingly and without lawful excuse is nothing less than

mass murder. Milosevic was indicted in The Hague for 385 victims. The

total victims of the 98 people executed for murder in the United States

in 1999 was 129. Our leaders killed between 500 and 1800.

That is why, starting in April of last year and continuing to the

present day, dozens of lawyers and law professors, a pan-American

association representing hundreds of jurists, some elected legislators,

and thousands of private citizens from around the world, have lodged

formal complaints with the International Criminal Tribunal in the Hague

charging NATO leaders with war crimes.

The particular complaint I am involved in was filed in May, 1999 and

names 68 individuals, including all the heads of government, foreign

ministers and defense ministers of the 19 NATO countries (including US

President Clinton, Secretaries Cohen and Albright, Canadian Prime

Minister Chretien, Ministers Axworthy and Eggleton and so on down the

list), and the highest ranking NATO officials, from then Secretary

General Javier Solana, through Generals Wesley Clark, Michael Short, and

official spokesman Jamie Shea.

The charges against them include the following:

Grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, contrary to

article 2 of the Statue of the Tribunal, namely the following acts

against persons or property protected under the provisions of the

relevant Geneva Convention: (a) wilful killing; (c) wilfully causing

great suffering or serious injury to body or health; (d) extensive

destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military

necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly.

Violations of the laws or customs of war, contrary to Article 3 namely:

(a) employment of poisonous weapons or other weapons to cause

unnecessary suffering; (b) wanton destruction of cities, towns or

villages, or devastation not justified by military necessity; (c)

attack, or bombardment, by whatever means, of undefended towns,

villages, dwellings, or buildings;(d) seizure of, destruction or willful

damage done to institutions dedicated to religion, charity and

education, the arts and sciences, historic monuments and works of art

and science.

Crimes against humanity contrary to Article 5, namely: (a) murder; (i)

other inhumane acts.

Article 7 of the Statute provides for "individual criminal

responsibility" thus:

1. A person who planned, instigated, ordered, committed or otherwise

aided and abetted in the planning, preparation or execution of a crime

referred to in articles 2 to 5 of the present Statute, shall be

individually responsible for the crime.

2. The official position of any accused person, whether as Head of State

or Government or as a responsible Government official, shall not relieve

such person of criminal responsibility or mitigate punishment.

3. The fact that any of the acts referred to in articles 2 to 5 of the

present Statute was committed by a subordinate does not relieve his

superior of criminal responsibility if he knew or had reason to know

that the subordinate was about to commit such acts or had done so and

the superior failed to take the necessary and reasonable measures to

prevent such acts or to punish the perpetrators thereof.

We have been in frequent contact with the Tribunal, travelling to the

Hague twice to argue our case with Chief Prosecutors Louise Arbour and

Carla Del Ponte and their legal advisers, filing evidence, legal briefs

and arguments in support of the case. I am filing with this Committee a

book of the evidence we have filed with the tribunal. I understand that

you already have the two volumes prepared by the government of

Yugoslavia. I would point out that these volumes have been confirmed as

"largely credible" by the Human Rights Watch Report.

Recently, Justice Del Ponte disclosed that she was studying an internal

document analyzing the many claims that have been made against NATO. My

latest word from her (February 8) is that she is still studying the

case.

Justice Del Ponte has said that if she is not prepared to prosecute NATO

she should pack up and go home, and I have to agree with her, because,

in that case, the Tribunal would be doing far more harm than good, only

legitimating NATO's violent lawlessness against people unlucky enough to

be ruled by "indicted war criminals", as opposed to the un-indicted kind

that govern the NATO countries.

This was the very purpose for which the United States sponsored this

tribunal in the first place, at least according to Michael Scharf,

Attorney-Advisor with the U.S. State Department, who, under Madeleine

Albright's instructions, actually drafted the Security Council

resolution establishing the Tribunal.

"the tribunal was widely perceived within the government as little more

than a public relations device and as a potentially useful policy

tool...Indictments also would serve to isolate offending leaders

diplomatically, strengthen the hand of their domestic rivals and fortify

the international political will to employ economic sanctions or use

force" (The Washington Post, October 3, 1999)

I must confess to you that my colleagues and I and the thousands of

others who have complained to the Tribunal have grave doubts about its

impartiality. We have given it the benefit of every doubt even in the

face of mounting evidence that it didn't deserve it: when, in January,

1999, then prosecutor Judge Louise Arbour made a rather dramatic

appearance at the border of Kosovo, lending credibility to contested

American accounts of atrocities at Racak, a precipitating justification

of the war itself; when, only days after the bombing had commenced, she

made an announcement of the Arkan indictment that had been secret from

1997; when she made television appearances with NATO leader Robin Cook,

already the subject of numerous complaints during the war to receive war

crimes dossiers; when she met with Madeleine Albright, herself by then

the subject of well-grounded complaints before the tribunal, and

Albright took the opportunity to announce that the United States was the

major provider of funds to the Tribunal; when, two weeks later, in the

midst of bombing, Judge Arbour announced the indictment of Milosevic, on

the basis of undisclosed evidence, for Racak and events which had

occurred only six weeks earlier in the middle of a war zone – on what,

in other words, must have been very flimsy and suspicious evidence; and

when, at the conclusion of the bombing Judge Arbour handed over the

investigation of war crimes in Kosovo to NATO countries' police forces

themselves - notwithstanding that they had every motive to falsify the

evidence.

I am sad to say, because the former prosecutor is now a judge of the

Supreme Court of Canada and an old colleague and friend of mine, of whom

we all want to be proud, that these could not be regarded as the acts of

an impartial prosecutor. Not when NATO was in the midst of a disastrous

war in flagrant violation of international law.

We sincerely hoped for better things from Judge Del Ponte coming as she

did from a country outside of the NATO alliance. But our expectations

have been progressively lowered. First, when she declared, immediately

upon taking the job, that her priorities were the prosecution of

Milosevic, something which clearly suited the NATO countries but which,

as we told her in November, could in no way be compatible with her sworn

duties. A prosecutor cannot declare that she is going to concentrate

only on some crimes and grant effective immunity to other criminals.

Then, when she made the observation that she was indeed investigating

complaints against NATO, and NATO reacted in its typically outrageous

fashion by attacking the Tribunal, Judge Del Ponte quickly issued

unseemly appeasing statements and went on a conciliatory mission to

Brussels.

I am saying all this to put the Committee on guard against delegating

its own judgment to this Tribunal which was set up as an instrument of

United States foreign policy and has given us so many grounds to suspect

that it sees itself the same way. Whatever this Tribunal decides to do

or not to do, it is incumbent on this Committee to scrutinize its

reasons and the evidence with the utmost care.

Let me end by citing to you the words of Justice Robert Jackson from his

opening statement to the Nurnberg Tribunal on November 21, 1945:

"But the ultimate step in avoiding periodic wars, which are inevitable

in

a system of international lawlessness, is to make statesmen responsible

to law. And let me make clear that while this law is first applied

against German aggressors, the law includes, and if it is to serve a

useful purpose it must condemn aggression by any other nations,

including those which sit here now in judgment. We are able to do away

with domestic tyranny and violence and aggression by those in power

against the rights of their own people only when we make all men

answerable to the law." (The Nurnberg Case As Presented by Robert H.

Jackson, Chief Counsel for the United States (New York: Cooper Square

Publishers Inc, 1971) at page 93)

--------- COORDINAMENTO ROMANO PER LA JUGOSLAVIA -----------

RIMSKI SAVEZ ZA JUGOSLAVIJU

e-mail: crj@... - URL: http://marx2001.org/crj

http://www.egroups.com/group/crj-mailinglist/

------------------------------------------------------------

SECONDA PARTE

In un precedente messaggio

( http://www.egroups.com/group/crj-mailinglist/79.html? )

abbiamo riportato alcune delle audizioni tenute ad Ottawa, alla Camera

dei Comuni, dinanzi allo Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and

International Trade da parte di varie personalita' ritenute a vario

titolo "informate sui fatti" riguardo alla aggressione della NATO contro

la Repubblica Federale di Jugoslavia.

Continuiamo ora con la seconda parte del contributo di SERGE TRIFKOVIC,

professore di storia, responsabile per gli esteri di "Chronicles -

Magazine of American Culture", e con il contributo di MICHAEL MANDEL,

professore di diritto alla Osgoode Hall Law School, York University,

Toronto, che insieme ad altri avvocati ha presentato denuncia contro la

NATO al Tribunale dell'Aia per i crimini commessi sul territorio della

ex-RFSJ. La denuncia giace, tuttora "insabbiata", in qualche cassetto di

Carla dal Ponte.

Tutti i documenti sono stati diffusi dalla lista stopnat-@...

------- Forwarded Message Follows -------

Date sent: Thu, 24 Feb 2000 16:00:58 -0500

From: "minja m." <minja@...>

Send reply to: minja@...

To: KPAJ 3A HATO <kpaj-3a-hato@...>

Subject: Srdja Trifkovic in Ottawa House of Commons - Pt.

2

Trifkovic in Ottawa House of Commons - Pt. 2

HOUSE OF COMMONS - CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES

STANDING COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND INTERNATIONAL

TRADE -

COMITE PERMANENT DES AFFAIRES ETRANGERES ET DU

COMMERCE INTERNATIONAL

UNEDITED COPY - COPIE NON EDITEE

• 0927 EVIDENCE

[Recorded by Electronic Apparatus]

Ottawa, Thursday, February 17, 2000

[English]

The Chairman (Mr. Bill Graham (Toronto Centre-Rosedale, Lib.)):

Colleagues, I'm going to call this meeting to order. So I'll ask the

people at the back of the room if they're going to have conversations to

go outside. I'm going to ask Ms. Swann from the Ottawa Serbian Heritage

Society if She could go first. Then we'll put Mr. Trifkovic. Mr. Dyer

hasn't arrived yet. I just want to warn everybody it may be a bit

chaotic

this morning. I'm not saying it isn't always chaotic but it may be more

chaotic than usual because we may be called for votes and this happened

the last time. So I apologize to the witnesses first if we're called out

of the room for votes. It just seems to be a bit- The House seems dans

un

peu de perturbation comme on dirait peut-être dans la langue française,

n'est-ce pas, and so we'll just have to deal with that if it occurs.

Otherwise we'll go on. But I'd ask the witnesses if you keep yourself To

10 minutes each and then we'll move to questions. [...] Mr. Trifkovic...

Mr. Serge Trifkovic (Individual Presentation): [... Text of presentation

as previously distributed... Transcript of ensuing Q&A follows herewith]

The Chairman: Thank you, sir. [... A member asked if it was preferable

to

have a world court to deal with human rights violations, or ad-hoc

tribunals for individual crisis areas...]

Ms. Serge Trifkovic: I was somewhat puzzled by the clear-cut choice

between the WCC [World Criminal Court] and ad hoc tribunals as the only

alternatives we are facing. To me it sounds a bit like the choice

between

cancer and leukemia. I do not believe that bureaucratically structured

and

politically motivated international quasi-judicial bodies are either

desirable or feasible. In any proper sense a "tribunal" is an impartial

forum for administration of justice. If the kangaroo court that goes by

the name of The Hague Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia is any indicator, I

think the lesson of that particular body is that its model of justice is

Moscow 1938, and not Nuremberg in 1946. It was formed on a purely

political agenda by the Security Council, on the basis of Chapter 7. The

way it has acted, in terms of its procedures, its rule of evidence and

finally the selection of people to be indicted and prosecuted - and also

its refusal to indict and prosecute people who at prima facie should be,

such as the leaders of the 19 NATO countries -only indicates that it is

a

political body par excellence. There is no reason at all why a WCC would

be any different because, obviously, if you have the likes of Clinton

and

Blair deciding what is "necessary" and "feasible" in terms of

intervention, ultimately they would be deciding what is "necessary" and

"feasible" in terms of prosecution. The kind of political discipline in

the world that this would impose is eerily reminiscent of the Brave New

World of Huxley or "1984." I suspect that bodies such as the ones that

you

are mentioning will only take us a step further in the direction of

global totalitarianism in which the local and national traditions of law

and justice and jurisprudence- which are meaningful because they have

evolved within the context of a genuine, authentic national culture-

will

be replaced by something that is global, something that is allegedly

universal and, therefore, of necessity, ideological.

The Chair: Okay. I'm sorry, we're going to have to move on. It's a very

fascinating discussion. • 1025 [English] I've got to leave with with the

thought that you've always got to answer alternatives so I'll come to

you

and ask "What's your alternative". My alternative is that there's going

to

be United States imperial courts applying their jurisdiction around the

world to enforce it, so that may be worse for you. Anyway, that's just-

Mr. Serge Trifkovic: My alternative is to rediscover the beauty of a

society of nations in which enlightened national interests, based upon

the

Golden Rule of "I will not deny to anyone what I am asking for myself",

will be the basis of law and the basis of international relations. I am

not claiming that it was a long-lost golden age in Europe between

1815-1914, that we ought to yearn for in terms of reactionary nostalgia.

I'm simply saying that what we are offered as a replacement in the

Blairites' and Clintonistas' brave new world is infinitely worse and

infinitely more frightening.

Mr. Chuck Strahl: Well, you asked.

The Chair: I asked, and that may be.We're going to go to Ms. Augustine

and

then we're going back to Mr. Strahl and Mr. Robinson.

Ms. Jean Augustine (Etobicoke-Lakeshore, Lib.): Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

[...]

I am grappling with what is the future of Kosovo, is it going to be an

international protectorate? Is it going to be an entity no longer linked

[to Serbia-Yugoslavia]? [...]

Mr. Serge Trifkovic: I would like to make a few comments about the

future because we keep forgetting the broad picture, what will happen in

the long term. The Kosovo crisis is primarily the result of the U.S.

involvement In the Kosovo situation. Until the moment Dick Holbrooke

decided that this was something they would tackle in a big way, it was -

I

insist - a low-level, unremarkable conflict, the likes of which we see

all

over the world, all of the time. At the moment there is a whole series

of

geopolitical reasons why the Washington administration wants to be

involved in the Balkans. I'm afraid we have no time to go into those in

any detail. But the important thing for the members of this Committee to

remember is that you shouldn't take the "humanitarian" and other alibis

as

face value. You should always assume that there is an agenda behind it.

One of them is to have a U.S. foothold in the European mainland that

will

not be subject to the ups-and-downs of the trans-Atlantic relationship,

so

that if and when the Germans, the French and others decide to create a

European Defence structure that will gradually detach West Europeans

from

NATO, which will ultimately lead to the closure of U.S. bases in Naples

and in Frankfurt and in Munich, there will be the assets in Skopje, and

in

Pristina, and in Tuzla, that will provide both the physical and the

political and military U.S. presence that will not be affected by such a

change in the relationship. When I say there are geopolitical reasons

which have a logic of their own, I am not claiming that in this

particular

case we can establish a definite sequence of events. • 1105 [English]

I'm

simply saying that humanitarian and moralistic claims by themselves are

neither a sufficient nor necessary explanation. In order to look at

Kosovo

in the longer term we have to ask the question: what will happen if and

when the United States administration after Clinton, or even after

whoever

comes after Clinton, loses interest in the Balkans? At the moment

they're

creating the demand for their involvement by creating a whole series of

small, fragmented and unviable units that, by themselves, have neither

the

political, nor cultural, nor historic meaning - such as Dayton-Bosnia,

such as Kosovo, such as, tomorrow maybe, Sanjak or Montenegro, Vojvodina

or whatever. If and when the presence of the underwriters in the Balkans

are removed, we will have another bout of Hobbesian free-for-all. And

that

is the tragedy of it all, because what is being done right now is not

the

foundation for a solid, just and durable peace, but just an

improvization

on an ad-hoc basis. It bears no relation to history, no relation to the

continuity of the political and cultural development in that part of

the

world, but satisfies the needs of the moment. I'm saying this not as

someone born in Serbia, but someone who is trying to look at the

political

essence of the problem - that so far the U.S. administration has

followed

the principle that all of the ethnic groups in the area can be satisfied

at the expense of the Serbs. The result is a sort of Carthaginian peace

imposed upon the Serbian nation that will create a constant source of

revanchist resentment among the Serbs, and determination to turn the

tables once Uncle Sam loses interest. I feel that there will be a war

again: the Serbs will fight to return Kosovo to their own rule, because

they feel Kosovo to have been unjustly detached. And so, whatever

scenario

the people in Brussels, London, Washington, Ottawa, or Bonn decide for

Kosovo today, it will not be worth the paper it's written on if it

doesn't

bear any relation to the geopolitical realities in the long term, and

those realities are fairly simple. You will not be able to impose

something called "multicultural" Kosovo, "multi-ethnic" Kosovo if people

on the ground - and I have primarily the Albanians in mind - are

determined to have a mono-ethnic Kosovo. By including 25% Serbian

members

in any quasi-representative bodies you introduce, you will not re-invent

a

"multi-ethnic Kosovo" in which grannies are able to return to their

apartments. At the moment the only way people in Kosovo will feel safe

and

secure living in their communities is if you have a de facto petition.

Whether it is accompanied by a constitutional and political model that

will sanctify that partition is neither here nor there. But in the long

term you have to realize that an imposed "peace" on the Serb nation that

does not take into account the legitimate interests of the Serbs, that

does not take into account the sort of give and take in which each party

will feel that it has lost something as well as gained something, will

be

unviable, will be unjust, and will be - in the long term - the source of

another conflict.

The Chairman: Okay. [...]

Mr. Chuck Strahl: I'm going to pass to Mr. Robinson, but before I do, I

understand, Prof Trifkovic, you must leave shortly to catch a plane to

Europe- Mr. Serge Trifkovic: Actually, to Chicago- Mr. Chuck Strahl: To

Chicago. Mr. Serge Trifkovic: -and change to the plane for Amsterdam.

Mr.

Chuck Strahl: Right. Mr. Serge Trifkovic: I can stay for another 10

minutes. Mr. Chuck Strahl: Okay. When you're comfortable to leave just

leave. I want to say, then if you just do get up and go- Mr. Serge

Trifkovic: There will be no tears shed. Mr. Chuck Strahl: No. There will

be tears. They may be crocodile. They may be joy, who knows? But

certainly

I just want to say we appreciate very much you taking the time to come.

There's no doubt about it being a very interesting intervention. Please,

when you have to go, just feel free to get up and go and don't think us

rude if we don't properly acknowledge your very important contribution.

Thank you, sir. Mr. Robinson. Mr. Svend Robinson: I'm afraid I'll have

to

leave around the same time. I'm not sure if the tears will be quite as

intense, but- The Chair: If the tears are shed- Some hon. members: Ha,

ha.

The Chair: Mr. Robinson, the tears are shed when you arrive, not when

you

leave.

Mr. Svend Robinson: I just had two questions, I guess for Mr. Trifkovic

and Ms. Swann, in particular. First, I wonder if you could just perhaps

elaborate a bit on some of the concerns around the current situation in

Pancevo and what your knowledge is of the situation in Pancevo. I had

the

opportunity to visit there and

The situation had the potential of being an environmental disaster. I'm

just wondering what the current analysis is of the outcome of the

bombing

in that area and what sort of testing has been done, for example, of the

environment, the water, the air and so on. Because there were serious

concerns about that. My second question, again to both of you. I wonder

if

you could talk a little bit about • 1120 [English] about the

responsibility of Serbs in Kosovo for wrongdoing. The United Nations

High

Commission on Refugees documented quite powerfully a major exodus of

Kosovar Albanians before March 24. I'm sure you're familiar with those

reports. You've seen those reports. Figures as many as 90,000 who had

left

their homes, left their villages. After the bombing started, did the

bombing exacerbate the flow of people. I have no doubt that it did.

Certainly a number of people who I spoke with pointed out how in some

cases Serbs on the ground were pointing up into the sky and saying you

were responsible for NATO. They felt that they were under siege from the

KLA, the NATO bombs and obviously when people are defenceless on the

ground they're totally vulnerable. It was a coward's war in many

respects,

but nevertheless people were driven out in huge numbers. Hundreds of

thousands of people left and were driven out. I was on a road from

Pristina down to the border with Macedonia, went through village after

village which were like ghost towns, houses had been burned to the

ground

in many cases and there's culpability for that and I want to hear from

you, both of you, some acknowledgement that yes we have to deal with

this

as well as part of the reckoning that must come out of this tragic

series

of events.

Mr. Serge Trifkovic: I'll deal with the second one and then I'll have to

go. I think the important thing to bear in mind in the Balkans is there

are no white hats and black hats and that's the fundamental problem that

we have faced with the coverage of the war in the media, and with

quasi-academic analysis, and with political decision-making. Very early

on

in this conflict an overall perception of the culpability of the Serbs

for

the Krajina, Bosnia and Kosovo was created even though very often the

reasons the Serbs reacted in the Krajina are very similar to the reasons

the Albanians reacted in Kosovo and vice versa. In some cases, the Serbs

were de facto separatists, wanting to secede from the separating entity.

In other times, they were the unitarists. In both cases they were deemed

wrong. But if you try to quantify the evil on all sides, it's impossible

to say that the Serbs proved qualitatively, fundamentally worse than

other

groups. Right now the Serbs constitute the largest refugee population

outside sub-Saharan Africa. To say that the Serbs have done evil things

is

almost a truism because in the Balkan imbroglio all sides have done very

evil things. If you want the Serbs to beat their chests and shout mea

culpa, well indeed, maybe they should because the Patriarch warned them

against

adopting some of the techniques and some of the feelings of their

enemies as they experienced them in 1941 to 1945 in the so-called

independent state of Croatia. [...] If this was the war to return the

Albanians, or in the memorable words of the then-British defence

minister

"Serbs out, Albanians back, NATO in", nobody is talking about "Serbs

back"

in Kosovo these days... a quarter of a million displaced Serbs and other

non-Albanians under NATO, in the aftermath of NATO's victory. So I will

be

the first to admit that the Serbs have done bad things just as everybody

else has done bad things; but it doesn't mean we are now going to ask

the

question how deserving are the Croats of being bombed • 1125 [English]

because they contributed "collectively" to the exodus of a quarter of a

million Serbs from the Krajina? How deserving are the Muslims of

castigation and bombing because right now, the whole of Sarajevo-until

1991, the second largest Serbian town after Belgrade - is Serbenfrei?.

If

we are to re-establish a modicum of reality in this debate, we have to

bear in mind that human fallibility and human culpability is not the

exclusive prerogative of anyone single ethnic group. Thank you.

Mr. Svend J. Robinson: Mr. Dyer, were you wanting to comment?

Mr. Gwynn Dyer: I was particularly struck by the use of the word

"Serbenfrei" to describe the Serbian authorities' removal of the Serbian

population of Sarajevo after the Dayton Accords. There were Serbians in

that city who were driven from their homes by the Serbian police. I was

there; I saw it. The idea that the Albanian Muslims and the Bosnian

Muslims and the Croats bear equal responsibility-all of them have done

bad

things. Of course bad things happen in war but neither the total of

refugees nor the total of dead nor the evidence of massacre suggests in

any way that there is shared responsibility equally indistinguishably

among the ethnic groups of the Balkans. Now this may be to some extent

because the Serbs inherited the heavy weapons of the Yugoslav army and

had

the ability to do more damage; I recognize that. The Bosnian Muslims

didn't have heavy artillery to shell Serbian villages as the Serbs did

to

shell Sarajevo. But I do find the line of argument which suggests that

there can be no distinguished distinction between Vukovar and Srebrenica

on the one hand, and the Krajina on the other hand. The Krajina Mark Two

-

when it was the Serbs who lost their homes - rather Mark One, when it

was

the Croatian inhabitants who were driven. I think is a travesty.

Mr. Serge Trifkovic: To claim that the Krajina is less of a crime than

"Srebrenica," even though the Krajina resulted in between 9 thousand and

12 thousand Serbian deaths, is a very curious argument, both morally and

intellectually. But in particular, I find it reprehensible that Kosovo

is

still referred to as a "massacre" because "the Kosovo massacre" is one

of

the biggest lies, media-mediated political lies of the decade, if not

the

century. In perspective, when a few decades pass, it will belong to the

same category as the bayonetted Belgian babies by the Kaiser's army in

1914. [...]

----

House of Commons-Canada

Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade

Tuesday February 22, 2000

Testimony of Professor Michael Mandel

Personal Note

Allow me to tell you a little bit about myself and how I became involved

in this. I am a professor of law at Osgoode Hall Law School where I have

taught for 25 years. I specialize in criminal law and comparative

constitutional law with an emphasis on domestic and foreign tribunals,

including United Nations tribunals such as the International Criminal

Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. I have no personal interest in the

conflict in Yugoslavia – I have no Serbs or Albanians in my family and I

am not being paid by anyone. I became involved in this as a Canadian

lawyer who witnessed a flagrant violation of the law by my government

with unspeakably tragic results for innocent people of all the Yugoslav