Informazione

PRIMI FRUTTI DEL GENEROSO IMPEGNO DELLA NATO PER LA MACEDONIA

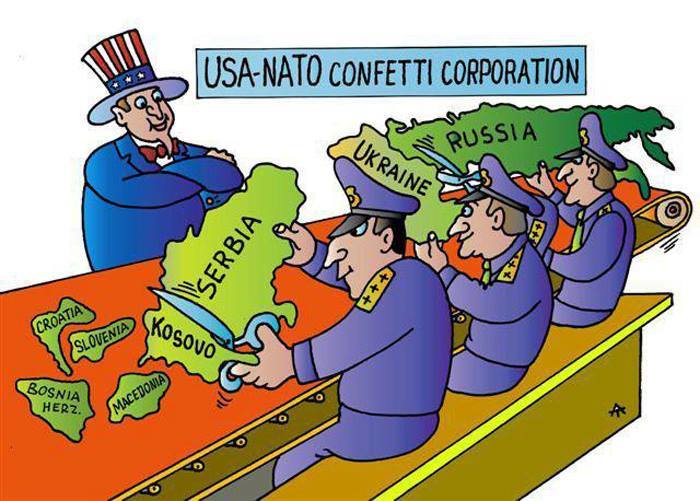

La lungimirante politica della NATO di sostegno al terrorismo

separatista grande-albanese, oltre a causare morte e distruzione

ed a consentire lo stanziamento di truppe occidentali su quel

territorio, incomincia gia' a dare i suoi frutti dal punto di

vista della trasformazione della societa' macedone.

Dopo decenni di pacifica convivenza, finalmente prendono piede

atteggiamenti separatisti-segregazionisti e la nota politica

del "boicottaggio" delle istituzioni dello Stato multinazionale,

analoga alla politica di auto-apartheid adottata dal partito e

dalle famiglie legate a Rugova in Kosovo - ed appoggiata

dall'arcipelago "pacifista" italiano - a partire dal 1990.

(I. Slavo)

MACEDONIA: MACEDONI E ALBANESI CHIEDONO CLASSI SEPARATE

(ANSA) - SKOPJE, 10 SET - Primo giorno di scuola oggi in Macedonia dove,

a dispetto dei piani di pace, l'odio etnico resta ancora molto forte. In

alcune scuole a Kumanovo e a Tetovo, zone maggiormente coinvolte nel

conflitto, gli studenti albanesi e macedoni hanno chiesto aule separate.

''Vorrebbero classi etnicamente pulite'' ha commentato sconsolato un

insegnante elementare. I 220 studenti albanesi dell'istituto superiore

''Goce Dolcev'' di Kumanovo, oggi hanno disertato le lezioni: ''Non

vogliamo iniziare l'anno scolatisco al fianco dei macedoni'' hanno

annunciato. Gli studenti minacciano di disertare la scuola fino a quando

la loro richiesta non verra' accolta. Situazione uguale e contraria a

Tetovo (nella zona nord-occidentale del paese), area a maggioranza

albanese: qui, nella scuola media ''Bratstvo Migjeni'', sono stati gli

alunni macedoni a non voler partecipare alle lezioni perche' non hanno

ottenuto ''classi separate dagli albanesi''. I genitori degli studenti

macedoni hanno detto di aver avviato contatti con il ministro

dell'Istruzione, Nenad Novkovski, al quale hanno formalizzato la

richiesta. Migliaia di altri studenti di entrambe le etnie non hanno

invece potuto presentarsi a scuola a causa delle condizioni di sicurezza

non ancora del tutto ristabilite. Le scuole sono rimaste chiuse in

gran parte dei villaggi montani della zona di Tetovo, aree tuttora sotto

il controllo della guerriglia albanese e nelle quali le lezioni sono

sospese sin da marzo dello scorso anno, quando inizio' il conflitto

armato. Nei villaggi della regione settentrionale di Kumanovo molte

scuole sono rimaste distrutte nel corso dei bombardamenti e non si sa

quando l'anno scolastico potra' cominciare. Assenti dalle aule anche le

migliaia di ragazzini (albanesi e macedoni) costretti a fuggire dalle

zone del conflitto, e che tuttora vivono come profughi in altre citta'

del paese o in Kosovo. (ANSA). BLL 10/09/2001 18:37

> http://wwww.ansa.it/balcani/macedonia/20010910183731970725.html

---

Questa lista e' curata da componenti del

Coordinamento Nazionale per la Jugoslavia (CNJ).

I documenti distribuiti non rispecchiano necessariamente

le posizioni ufficiali o condivise da tutto il CNJ, ma

vengono fatti circolare per il loro contenuto informativo al

solo scopo di segnalazione e commento ("for fair use only").

Archivio:

> http://www.domeus.it/circles/jugoinfo oppure:

> http://groups.yahoo.com/group/crj-mailinglist/messages

Per iscriversi al bollettino: <jugoinfo-subscribe@...>

Per cancellarsi: <jugoinfo-unsubscribe@...>

Per inviare materiali e commenti: <jugocoord@...>

---- Spot ------------------------------------------------------------

Il Tennis e' la tua passione?

Tutte le news sugli ultimi risultati, notizie inedite

e interviste nella Newsletter piu' in palla del momento!!!

Iscriviti a tennisnews-subscribe@...

Tennis.it ti offrira' il meglio del tennis direttamente nella tua casella email

http://www.domeus.it/ad3650160/domeus

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Per cancellarti da questo gruppo, invia un messaggio vuoto a: jugoinfo-unsubscribe@...

La lungimirante politica della NATO di sostegno al terrorismo

separatista grande-albanese, oltre a causare morte e distruzione

ed a consentire lo stanziamento di truppe occidentali su quel

territorio, incomincia gia' a dare i suoi frutti dal punto di

vista della trasformazione della societa' macedone.

Dopo decenni di pacifica convivenza, finalmente prendono piede

atteggiamenti separatisti-segregazionisti e la nota politica

del "boicottaggio" delle istituzioni dello Stato multinazionale,

analoga alla politica di auto-apartheid adottata dal partito e

dalle famiglie legate a Rugova in Kosovo - ed appoggiata

dall'arcipelago "pacifista" italiano - a partire dal 1990.

(I. Slavo)

MACEDONIA: MACEDONI E ALBANESI CHIEDONO CLASSI SEPARATE

(ANSA) - SKOPJE, 10 SET - Primo giorno di scuola oggi in Macedonia dove,

a dispetto dei piani di pace, l'odio etnico resta ancora molto forte. In

alcune scuole a Kumanovo e a Tetovo, zone maggiormente coinvolte nel

conflitto, gli studenti albanesi e macedoni hanno chiesto aule separate.

''Vorrebbero classi etnicamente pulite'' ha commentato sconsolato un

insegnante elementare. I 220 studenti albanesi dell'istituto superiore

''Goce Dolcev'' di Kumanovo, oggi hanno disertato le lezioni: ''Non

vogliamo iniziare l'anno scolatisco al fianco dei macedoni'' hanno

annunciato. Gli studenti minacciano di disertare la scuola fino a quando

la loro richiesta non verra' accolta. Situazione uguale e contraria a

Tetovo (nella zona nord-occidentale del paese), area a maggioranza

albanese: qui, nella scuola media ''Bratstvo Migjeni'', sono stati gli

alunni macedoni a non voler partecipare alle lezioni perche' non hanno

ottenuto ''classi separate dagli albanesi''. I genitori degli studenti

macedoni hanno detto di aver avviato contatti con il ministro

dell'Istruzione, Nenad Novkovski, al quale hanno formalizzato la

richiesta. Migliaia di altri studenti di entrambe le etnie non hanno

invece potuto presentarsi a scuola a causa delle condizioni di sicurezza

non ancora del tutto ristabilite. Le scuole sono rimaste chiuse in

gran parte dei villaggi montani della zona di Tetovo, aree tuttora sotto

il controllo della guerriglia albanese e nelle quali le lezioni sono

sospese sin da marzo dello scorso anno, quando inizio' il conflitto

armato. Nei villaggi della regione settentrionale di Kumanovo molte

scuole sono rimaste distrutte nel corso dei bombardamenti e non si sa

quando l'anno scolastico potra' cominciare. Assenti dalle aule anche le

migliaia di ragazzini (albanesi e macedoni) costretti a fuggire dalle

zone del conflitto, e che tuttora vivono come profughi in altre citta'

del paese o in Kosovo. (ANSA). BLL 10/09/2001 18:37

> http://wwww.ansa.it/balcani/macedonia/20010910183731970725.html

---

Questa lista e' curata da componenti del

Coordinamento Nazionale per la Jugoslavia (CNJ).

I documenti distribuiti non rispecchiano necessariamente

le posizioni ufficiali o condivise da tutto il CNJ, ma

vengono fatti circolare per il loro contenuto informativo al

solo scopo di segnalazione e commento ("for fair use only").

Archivio:

> http://www.domeus.it/circles/jugoinfo oppure:

> http://groups.yahoo.com/group/crj-mailinglist/messages

Per iscriversi al bollettino: <jugoinfo-subscribe@...>

Per cancellarsi: <jugoinfo-unsubscribe@...>

Per inviare materiali e commenti: <jugocoord@...>

---- Spot ------------------------------------------------------------

Il Tennis e' la tua passione?

Tutte le news sugli ultimi risultati, notizie inedite

e interviste nella Newsletter piu' in palla del momento!!!

Iscriviti a tennisnews-subscribe@...

Tennis.it ti offrira' il meglio del tennis direttamente nella tua casella email

http://www.domeus.it/ad3650160/domeus

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Per cancellarti da questo gruppo, invia un messaggio vuoto a: jugoinfo-unsubscribe@...

Subject: Ousmane Bin Laden

Date: Thu, 13 Sep 2001 07:43:50 -0400

From: Michel Chossudovsky <chossudovsky@...>

To: (Recipient list suppressed)

WHO IS OUSMANE BIN LADEN?

by Michel Chossudovsky

Professor of Economics,

University of Ottawa

Centre for Research on Globalisation (CRG) at

http:/globalresearch.ca.

The url of this article is

http://globalresearch.ca/articles/CHO109C.html

Posted 12 September 2001

A few hours after the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Centre

and the Pentagon, the Bush administration concluded without

supporting evidence, that "Ousmane bin Laden and his al-Qaeda

organisation were prime suspects". CIA Director George Tenet

stated that bin Laden has the capacity to plan ``multiple attacks

with little or no warning.'' Secretary of State Colin Powell called

the attacks "an act of war" and President Bush confirmed in an

evening televised address to the Nation that he would "make no

distinction between the terrorists who committed these acts and

those who harbor them". Former CIA Director James Woolsey

pointed his finger at "state sponsorship," implying the complicity

of one or more foreign governments. In the words of former

National Security Adviser, Lawrence Eagleburger, "I think we

will show when we get attacked like this, we are terrible in our

strength and in our retribution."

Meanwhile, parroting official statements, the Western media

mantra has approved the launching of "punitive actions" directed

against civilian targets in the Middle East. In the words of

William Saffire writing in the New York Times: "When we

reasonably determine our attackers' bases and camps, we must

pulverize them -- minimizing but accepting the risk of collateral

damage -- and act overtly or covertly to destabilize terror's

national hosts".

The following text outlines the history of Ousmane Bin Laden and

the links of the Islamic "Jihad" to the formulation of US foreign

policy during the Cold War and its aftermath.

* * *

Prime suspect in the New York and Washington terrorists

attacks, branded by the FBI as an "international terrorist" for his

role in the African US embassy bombings, Saudi born Ousmane

bin Laden was recruited during the Soviet-Afghan war "ironically

under the auspices of the CIA, to fight Soviet invaders". 1

In 1979 "the largest covert operation in the history of the CIA"

was launched in response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan

in support of the pro-Communist government of Babrak Kamal.2:

"With the active encouragement of the CIA and Pakistan's ISI

[Inter Services Intelligence], who wanted to turn the Afghan jihad

into a global war waged by all Muslim states against the Soviet

Union, some 35,000 Muslim radicals from 40 Islamic countries

joined Afghanistan's fight between 1982 and 1992. Tens of

thousands more came to study in Pakistani madrasahs.

Eventually more than 100,000 foreign Muslim radicals were

directly influenced by the Afghan jihad."3

The Islamic "jihad" was supported by the United States and

Saudi Arabia with a significant part of the funding generated from

the Golden Crescent drug trade:

"In March 1985, President Reagan signed National Security

Decision Directive 166,...[which] authorize[d] stepped-up covert

military aid to the mujahideen, and it made clear that the secret

Afghan war had a new goal: to defeat Soviet troops in

Afghanistan through covert action and encourage a Soviet

withdrawal. The new covert U.S. assistance began with a

dramatic increase in arms supplies -- a steady rise to 65,000

tons annually by 1987, ... as well as a "ceaseless stream" of CIA

and Pentagon specialists who traveled to the secret headquarters

of Pakistan's ISI on the main road near Rawalpindi, Pakistan.

There the CIA specialists met with Pakistani intelligence officers

to help plan operations for the Afghan rebels."4

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) using Pakistan's military

Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) played a key role in training the

Mujahideen. In turn, the CIA sponsored guerrilla training was

integrated with the teachings of Islam:

"Predominant themes were that Islam was a complete

socio-political ideology, that holy Islam was being violated by the

atheistic Soviet troops, and that the Islamic people of

Afghanistan should reassert their independence by overthrowing

the leftist Afghan regime propped up by Moscow."5

PAKISTAN'S INTELLIGENCE APPARATUS

Pakistan's ISI was used as a "go-between". The CIA covert

support to the "jihad" operated indirectly through the Pakistani

ISI, --i.e. the CIA did not channel its support directly to the

Mujahideen. In other words, for these covert operations to be

"successful", Washington was careful not to reveal the ultimate

objective of the "jihad", which consisted in destroying the Soviet

Union.

In the words of CIA's Milton Beardman "We didn't train Arabs".

Yet according to Abdel Monam Saidali, of the Al-aram Center for

Strategic Studies in Cairo, bin Laden and the "Afghan Arabs" had

been imparted "with very sophisticated types of training that was

allowed to them by the CIA" 6

CIA's Beardman confirmed, in this regard, that Ousmane bin

Laden was not aware of the role he was playing on behalf of

Washington. In the words of bin Laden (quoted by Beardman):

"neither I, nor my brothers saw evidence of American help". 7

Motivated by nationalism and religious fervor, the Islamic

warriors were unaware that they were fighting the Soviet Army

on behalf of Uncle Sam. While there were contacts at the upper

levels of the intelligence hierarchy, Islamic rebel leaders in

theatre had no contacts with Washington or the CIA.

With CIA backing and the funneling of massive amounts of US

military aid, the Pakistani ISI had developed into a "parallel

structure wielding enormous power over all aspects of

government". 8 The ISI had a staff composed of military and

intelligence officers, bureaucrats, undercover agents and

informers, estimated at 150,000. 9

Meanwhile, CIA operations had also reinforced the Pakistani

military regime led by General Zia Ul Haq:

"''Relations between the CIA and the ISI [Pakistan's military

intelligence] had grown increasingly warm following [General]

Zia's ouster of Bhutto and the advent of the military regime,'...

During most of the Afghan war, Pakistan was more aggressively

anti-Soviet than even the United States. Soon after the Soviet

military invaded Afghanistan in 1980, Zia [ul Haq] sent his ISI

chief to destabilize the Soviet Central Asian states. The CIA only

agreed to this plan in October 1984.... `the CIA was more

cautious than the Pakistanis.' Both Pakistan and the United

States took the line of deception on Afghanistan with a public

posture of negotiating a settlement while privately agreeing that

military escalation was the best course."10

THE GOLDEN CRESCENT DRUG TRIANGLE

The history of the drug trade in Central Asia is intimately related

to the CIA's covert operations. Prior to the Soviet-Afghan war,

opium production in Afghanistan and Pakistan was directed to

small regional markets. There was no local production of heroin.

11 In this regard, Alfred McCoy's study confirms that within two

years of the onslaught of the CIA operation in Afghanistan, "the

Pakistan-Afghanistan borderlands became the world's top heroin

producer, supplying 60 percent of U.S. demand. In Pakistan, the

heroin-addict population went from near zero in 1979... to 1.2

million by 1985 -- a much steeper rise than in any other

nation":12

"CIA assets again controlled this heroin trade. As the

Mujahideen guerrillas seized territory inside Afghanistan, they

ordered peasants to plant opium as a revolutionary tax. Across

the border in Pakistan, Afghan leaders and local syndicates under

the protection of Pakistan Intelligence operated hundreds of

heroin laboratories. During this decade of wide-open

drug-dealing, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency in Islamabad

failed to instigate major seizures or arrests ... U.S. officials had

refused to investigate charges of heroin dealing by its Afghan

allies `because U.S. narcotics policy in Afghanistan has been

subordinated to the war against Soviet influence there.' In 1995,

the former CIA director of the Afghan operation, Charles Cogan,

admitted the CIA had indeed sacrificed the drug war to fight the

Cold War. `Our main mission was to do as much damage as

possible to the Soviets. We didn't really have the resources or

the time to devote to an investigation of the drug trade,'... `I don't

think that we need to apologize for this. Every situation has its

fallout.... There was fallout in terms of drugs, yes. But the main

objective was accomplished. The Soviets left Afghanistan.'"13

IN THE WAKE OF THE COLD WAR

\In the wake of the Cold War, the Central Asian region is not only

strategic for its extensive oil reserves, it also produces three

quarters of the World's opium representing multibillion dollar

revenues to business syndicates, financial institutions,

intelligence agencies and organized crime. The annual proceeds

of the Golden Crescent drug trade (between 100 and 200 billion

dollars) represents approximately one third of the Worldwide

annual turnover of narcotics, estimated by the United Nations to

be of the order of $500 billion.14

With the disintegration of the Soviet Union, a new surge in opium

production has unfolded. (According to UN estimates, the

production of opium in Afghanistan in 1998-99 -- coinciding with

the build up of armed insurgencies in the former Soviet

republics-- reached a record high of 4600 metric tons.15

Powerful business syndicates in the former Soviet Union allied

with organized crime are competing for the strategic control over

the heroin routes.

The ISI's extensive intelligence military-network was not

dismantled in the wake of the Cold War. The CIA continued to

support the Islamic "jihad" out of Pakistan. New undercover

initiatives were set in motion in Central Asia, the Caucasus and

the Balkans. Pakistan's military and intelligence apparatus

essentially "served as a catalyst for the disintegration of the

Soviet Union and the emergence of six new Muslim republics in

Central Asia." 16.

Meanwhile, Islamic missionaries of the Wahhabi sect from Saudi

Arabia had established themselves in the Muslim republics as

well as within the Russian federation encroaching upon the

institutions of the secular State. Despite its anti-American

ideology, Islamic fundamentalism was largely serving

Washington's strategic interests in the former Soviet Union.

Following the withdrawal of Soviet troops in 1989, the civil war in

Afghanistan continued unabated. The Taliban were being

supported by the Pakistani Deobandis and their political party the

Jamiat-ul-Ulema-e-Islam (JUI). In 1993, JUI entered the

government coalition of Prime Minister Benazzir Bhutto. Ties

between JUI, the Army and ISI were established. In 1995, with

the downfall of the Hezb-I-Islami Hektmatyar government in

Kabul, the Taliban not only instated a hardline Islamic

government, they also "handed control of training camps in

Afghanistan over to JUI factions..." 17

And the JUI with the support of the Saudi Wahhabi movements

played a key role in recruiting volunteers to fight in the Balkans

and the former Soviet Union.

Jane Defense Weekly confirms in this regard that "half of Taliban

manpower and equipment originate[d] in Pakistan under the ISI"

18 In fact, it would appear that following the Soviet withdrawal

both sides in the Afghan civil war continued to receive covert

support through Pakistan's ISI. 19

In other words, backed by Pakistan's military intelligence (ISI)

which in turn was controlled by the CIA, the Taliban Islamic

State was largely serving American geopolitical interests. The

Golden Crescent drug trade was also being used to finance and

equip the Bosnian Muslim Army (starting in the early 1990s) and

the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). In last few months there is

evidence that Mujahideen mercenaries are fighting in the ranks of

KLA-NLA terrorists in their assaults into Macedonia.

No doubt, this explains why Washington has closed its eyes on

the reign of terror imposed by the Taliban including the blatant

derogation of women's rights, the closing down of schools for

girls, the dismissal of women employees from government offices

and the enforcement of "the Sharia laws of punishment".20

THE WAR IN CHECHNYA

With regard to Chechnya, the main rebel leaders Shamil Basayev

and Al Khattab were trained and indoctrinated in CIA sponsored

camps in Afghanistan and Pakistan. According to Yossef

Bodansky, director of the U.S. Congress's Task Force on

Terrorism and Unconventional Warfare, the war in Chechnya had

been planned during a secret summit of HizbAllah International

held in 1996 in Mogadishu, Somalia. 21 The summit, was attended

by Osama bin Laden and high-ranking Iranian and Pakistani

intelligence officers. In this regard, the involvement of Pakistan's

ISI in Chechnya "goes far beyond supplying the Chechens with

weapons and expertise: the ISI and its radical Islamic proxies are

actually calling the shots in this war". 22

Russia's main pipeline route transits through Chechnya and

Dagestan. Despite Washington's perfunctory condemnation of

Islamic terrorism, the indirect beneficiaries of the Chechen war

are the Anglo-American oil conglomerates which are vying for

control over oil resources and pipeline corridors out of the

Caspian Sea basin.

The two main Chechen rebel armies (respectively led by

Commander Shamil Basayev and Emir Khattab) estimated at

35,000 strong were supported by Pakistan's ISI, which also

played a key role in organizing and training the Chechen rebel

army:

"[In 1994] the Pakistani Inter Services Intelligence arranged for

Basayev and his trusted lieutenants to undergo intensive Islamic

indoctrination and training in guerrilla warfare in the Khost

province of Afghanistan at Amir Muawia camp, set up in the

early 1980s by the CIA and ISI and run by famous Afghani

warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. In July 1994, upon graduating from

Amir Muawia, Basayev was transferred to Markaz-i-Dawar

camp in Pakistan to undergo training in advanced guerrilla tactics.

In Pakistan, Basayev met the highest ranking Pakistani military

and intelligence officers: Minister of Defense General Aftab

Shahban Mirani, Minister of Interior General Naserullah Babar,

and the head of the ISI branch in charge of supporting Islamic

causes, General Javed Ashraf, (all now retired). High-level

connections soon proved very useful to Basayev.23

Following his training and indoctrination stint, Basayev was

assigned to lead the assault against Russian federal troops in the

first Chechen war in 1995. His organization had also developed

extensive links to criminal syndicates in Moscow as well as ties

to Albanian organized crime and the Kosovo Liberation Army

(KLA). In 1997-98, according to Russia's Federal Security

Service (FSB) "Chechen warlords started buying up real estate in

Kosovo... through several real estate firms registered as a cover

in Yugoslavia" 24

Basayev's organisation has also been involved in a number of

rackets including narcotics, illegal tapping and sabotage of

Russia's oil pipelines, kidnapping, prostitution, trade in

counterfeit dollars and the smuggling of nuclear materials (See

Mafia linked to Albania's collapsed pyramids, 25 Alongside the

extensive laundering of drug money, the proceeds of various illicit

activities have been funneled towards the recruitment of

mercenaries and the purchase of weapons.

During his training in Afghanistan, Shamil Basayev linked up with

Saudi born veteran Mujahideen Commander "Al Khattab" who

had fought as a volunteer in Afghanistan. Barely a few months

after Basayev's return to Grozny, Khattab was invited (early

1995) to set up an army base in Chechnya for the training of

Mujahideen fighters. According to the BBC, Khattab's posting to

Chechnya had been "arranged through the Saudi-Arabian based

[International] Islamic Relief Organisation, a militant religious

organisation, funded by mosques and rich individuals which

channeled funds into Chechnya".26

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Since the Cold War era, Washington has consciously supported

Ousmane bin Laden, while at same time placing him on the FBI's

"most wanted list" as the World's foremost terrorist.

While the Mujahideen are busy fighting America's war in the

Balkans and the former Soviet Union, the FBI --operating as a

US based Police Force- is waging a domestic war against

terrorism, operating in some respects independently of the CIA

which has --since the Soviet-Afghan war-- supported

international terrorism through its covert operations.

In a cruel irony, while the Islamic jihad --featured by the Bush

Adminstration as "a threat to America"-- is blamed for the

terrorist assaults on the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon,

these same Islamic organisations constitute a key instrument of

US military-intelligence operations in the Balkans and the former

Soviet Union.

In the wake of the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington,

the truth must prevail to prevent the Bush Adminstration together

with its NATO partners from embarking upon a military adventure

which threatens the future of humanity.

ENDNOTES

Hugh Davies, International: `Informers' point the finger at bin

Laden; Washington on alert for suicide bombers, The Daily

Telegraph, London, 24 August 1998.

See Fred Halliday, "The Un-great game: the Country that lost the

Cold War, Afghanistan, New Republic, 25 March 1996):

Ahmed Rashid, The Taliban: Exporting Extremism, Foreign

Affairs, November-December 1999.

Steve Coll, Washington Post, July 19, 1992.

Dilip Hiro, Fallout from the Afghan Jihad, Inter Press Services, 21

November 1995.

Weekend Sunday (NPR); Eric Weiner, Ted Clark; 16 August

1998.

Ibid.

Dipankar Banerjee; Possible Connection of ISI With Drug

Industry, India Abroad, 2 December 1994.

Ibid

See Diego Cordovez and Selig Harrison, Out of Afghanistan: The

Inside Story of the Soviet Withdrawal, Oxford university Press,

New York, 1995. See also the review of Cordovez and Harrison in

International Press Services, 22 August 1995.

Alfred McCoy, Drug fallout: the CIA's Forty Year Complicity in

the Narcotics Trade. The Progressive; 1 August 1997.

Ibid

Ibid.

Douglas Keh, Drug Money in a changing World, Technical

document no 4, 1998, Vienna UNDCP, p. 4. See also Report of

the International Narcotics Control Board for 1999,

E/INCB/1999/1 United Nations Publication, Vienna 1999, p

49-51, And Richard Lapper, UN Fears Growth of Heroin Trade,

Financial Times, 24 February 2000.

Report of the International Narcotics Control Board, op cit, p

49-51, see also Richard Lapper, op. cit.

International Press Services, 22 August 1995.

Ahmed Rashid, The Taliban: Exporting Extremism, Foreign

Affairs, November- December, 1999, p. 22.

Quoted in the Christian Science Monitor, 3 September 1998)

Tim McGirk, Kabul learns to live with its bearded conquerors,

The Independent, London, 6 November1996.

See K. Subrahmanyam, Pakistan is Pursuing Asian Goals, India

Abroad, 3 November 1995.

Levon Sevunts, Who's calling the shots?: Chechen conflict finds

Islamic roots in Afghanistan and Pakistan, 23 The Gazette,

Montreal, 26 October 1999..

Ibid

Ibid.

See Vitaly Romanov and Viktor Yadukha, Chechen Front Moves

To Kosovo Segodnia, Moscow, 23 Feb 2000.

The European, 13 February 1997, See also Itar-Tass, 4-5

January 2000.

BBC, 29 September 1999).

The URL of this article is:

http://globalresearch.ca/articles/CHO109C.html

Copyright Michel Chossudovsky, Montreal, September 2001. All

rights reserved. Centre for Research on Globalisation at

http://globalresearch.ca Permission is granted to post this text on

non-commercial community internet sites, provided the source

and the URL are indicated, the essay remains intact and the

copyright note is displayed. To publish this text in printed and/or

other forms, including commercial internet sites and excerpts,

contact the author at chossudovsky@..., fax:

1-514-4256224.

---

Questa lista e' curata da componenti del

Coordinamento Nazionale per la Jugoslavia (CNJ).

I documenti distribuiti non rispecchiano necessariamente

le posizioni ufficiali o condivise da tutto il CNJ, ma

vengono fatti circolare per il loro contenuto informativo al

solo scopo di segnalazione e commento ("for fair use only").

Archivio:

> http://www.domeus.it/circles/jugoinfo oppure:

> http://groups.yahoo.com/group/crj-mailinglist/messages

Per iscriversi al bollettino: <jugoinfo-subscribe@...>

Per cancellarsi: <jugoinfo-unsubscribe@...>

Per inviare materiali e commenti: <jugocoord@...>

---- Spot ------------------------------------------------------------

PERCHE' ASPETTARE UN'EVENTO PER FARE REGALI!

Vacanze, idee regalo, liste nozze...

tutte le migliori offerte direttamente

nella vostra casella di posta!

http://www.domeus.it/ad3650330/valuemail.domeus

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Per cancellarti da questo gruppo, invia un messaggio vuoto a: jugoinfo-unsubscribe@...

Date: Thu, 13 Sep 2001 07:43:50 -0400

From: Michel Chossudovsky <chossudovsky@...>

To: (Recipient list suppressed)

WHO IS OUSMANE BIN LADEN?

by Michel Chossudovsky

Professor of Economics,

University of Ottawa

Centre for Research on Globalisation (CRG) at

http:/globalresearch.ca.

The url of this article is

http://globalresearch.ca/articles/CHO109C.html

Posted 12 September 2001

A few hours after the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Centre

and the Pentagon, the Bush administration concluded without

supporting evidence, that "Ousmane bin Laden and his al-Qaeda

organisation were prime suspects". CIA Director George Tenet

stated that bin Laden has the capacity to plan ``multiple attacks

with little or no warning.'' Secretary of State Colin Powell called

the attacks "an act of war" and President Bush confirmed in an

evening televised address to the Nation that he would "make no

distinction between the terrorists who committed these acts and

those who harbor them". Former CIA Director James Woolsey

pointed his finger at "state sponsorship," implying the complicity

of one or more foreign governments. In the words of former

National Security Adviser, Lawrence Eagleburger, "I think we

will show when we get attacked like this, we are terrible in our

strength and in our retribution."

Meanwhile, parroting official statements, the Western media

mantra has approved the launching of "punitive actions" directed

against civilian targets in the Middle East. In the words of

William Saffire writing in the New York Times: "When we

reasonably determine our attackers' bases and camps, we must

pulverize them -- minimizing but accepting the risk of collateral

damage -- and act overtly or covertly to destabilize terror's

national hosts".

The following text outlines the history of Ousmane Bin Laden and

the links of the Islamic "Jihad" to the formulation of US foreign

policy during the Cold War and its aftermath.

* * *

Prime suspect in the New York and Washington terrorists

attacks, branded by the FBI as an "international terrorist" for his

role in the African US embassy bombings, Saudi born Ousmane

bin Laden was recruited during the Soviet-Afghan war "ironically

under the auspices of the CIA, to fight Soviet invaders". 1

In 1979 "the largest covert operation in the history of the CIA"

was launched in response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan

in support of the pro-Communist government of Babrak Kamal.2:

"With the active encouragement of the CIA and Pakistan's ISI

[Inter Services Intelligence], who wanted to turn the Afghan jihad

into a global war waged by all Muslim states against the Soviet

Union, some 35,000 Muslim radicals from 40 Islamic countries

joined Afghanistan's fight between 1982 and 1992. Tens of

thousands more came to study in Pakistani madrasahs.

Eventually more than 100,000 foreign Muslim radicals were

directly influenced by the Afghan jihad."3

The Islamic "jihad" was supported by the United States and

Saudi Arabia with a significant part of the funding generated from

the Golden Crescent drug trade:

"In March 1985, President Reagan signed National Security

Decision Directive 166,...[which] authorize[d] stepped-up covert

military aid to the mujahideen, and it made clear that the secret

Afghan war had a new goal: to defeat Soviet troops in

Afghanistan through covert action and encourage a Soviet

withdrawal. The new covert U.S. assistance began with a

dramatic increase in arms supplies -- a steady rise to 65,000

tons annually by 1987, ... as well as a "ceaseless stream" of CIA

and Pentagon specialists who traveled to the secret headquarters

of Pakistan's ISI on the main road near Rawalpindi, Pakistan.

There the CIA specialists met with Pakistani intelligence officers

to help plan operations for the Afghan rebels."4

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) using Pakistan's military

Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) played a key role in training the

Mujahideen. In turn, the CIA sponsored guerrilla training was

integrated with the teachings of Islam:

"Predominant themes were that Islam was a complete

socio-political ideology, that holy Islam was being violated by the

atheistic Soviet troops, and that the Islamic people of

Afghanistan should reassert their independence by overthrowing

the leftist Afghan regime propped up by Moscow."5

PAKISTAN'S INTELLIGENCE APPARATUS

Pakistan's ISI was used as a "go-between". The CIA covert

support to the "jihad" operated indirectly through the Pakistani

ISI, --i.e. the CIA did not channel its support directly to the

Mujahideen. In other words, for these covert operations to be

"successful", Washington was careful not to reveal the ultimate

objective of the "jihad", which consisted in destroying the Soviet

Union.

In the words of CIA's Milton Beardman "We didn't train Arabs".

Yet according to Abdel Monam Saidali, of the Al-aram Center for

Strategic Studies in Cairo, bin Laden and the "Afghan Arabs" had

been imparted "with very sophisticated types of training that was

allowed to them by the CIA" 6

CIA's Beardman confirmed, in this regard, that Ousmane bin

Laden was not aware of the role he was playing on behalf of

Washington. In the words of bin Laden (quoted by Beardman):

"neither I, nor my brothers saw evidence of American help". 7

Motivated by nationalism and religious fervor, the Islamic

warriors were unaware that they were fighting the Soviet Army

on behalf of Uncle Sam. While there were contacts at the upper

levels of the intelligence hierarchy, Islamic rebel leaders in

theatre had no contacts with Washington or the CIA.

With CIA backing and the funneling of massive amounts of US

military aid, the Pakistani ISI had developed into a "parallel

structure wielding enormous power over all aspects of

government". 8 The ISI had a staff composed of military and

intelligence officers, bureaucrats, undercover agents and

informers, estimated at 150,000. 9

Meanwhile, CIA operations had also reinforced the Pakistani

military regime led by General Zia Ul Haq:

"''Relations between the CIA and the ISI [Pakistan's military

intelligence] had grown increasingly warm following [General]

Zia's ouster of Bhutto and the advent of the military regime,'...

During most of the Afghan war, Pakistan was more aggressively

anti-Soviet than even the United States. Soon after the Soviet

military invaded Afghanistan in 1980, Zia [ul Haq] sent his ISI

chief to destabilize the Soviet Central Asian states. The CIA only

agreed to this plan in October 1984.... `the CIA was more

cautious than the Pakistanis.' Both Pakistan and the United

States took the line of deception on Afghanistan with a public

posture of negotiating a settlement while privately agreeing that

military escalation was the best course."10

THE GOLDEN CRESCENT DRUG TRIANGLE

The history of the drug trade in Central Asia is intimately related

to the CIA's covert operations. Prior to the Soviet-Afghan war,

opium production in Afghanistan and Pakistan was directed to

small regional markets. There was no local production of heroin.

11 In this regard, Alfred McCoy's study confirms that within two

years of the onslaught of the CIA operation in Afghanistan, "the

Pakistan-Afghanistan borderlands became the world's top heroin

producer, supplying 60 percent of U.S. demand. In Pakistan, the

heroin-addict population went from near zero in 1979... to 1.2

million by 1985 -- a much steeper rise than in any other

nation":12

"CIA assets again controlled this heroin trade. As the

Mujahideen guerrillas seized territory inside Afghanistan, they

ordered peasants to plant opium as a revolutionary tax. Across

the border in Pakistan, Afghan leaders and local syndicates under

the protection of Pakistan Intelligence operated hundreds of

heroin laboratories. During this decade of wide-open

drug-dealing, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency in Islamabad

failed to instigate major seizures or arrests ... U.S. officials had

refused to investigate charges of heroin dealing by its Afghan

allies `because U.S. narcotics policy in Afghanistan has been

subordinated to the war against Soviet influence there.' In 1995,

the former CIA director of the Afghan operation, Charles Cogan,

admitted the CIA had indeed sacrificed the drug war to fight the

Cold War. `Our main mission was to do as much damage as

possible to the Soviets. We didn't really have the resources or

the time to devote to an investigation of the drug trade,'... `I don't

think that we need to apologize for this. Every situation has its

fallout.... There was fallout in terms of drugs, yes. But the main

objective was accomplished. The Soviets left Afghanistan.'"13

IN THE WAKE OF THE COLD WAR

\In the wake of the Cold War, the Central Asian region is not only

strategic for its extensive oil reserves, it also produces three

quarters of the World's opium representing multibillion dollar

revenues to business syndicates, financial institutions,

intelligence agencies and organized crime. The annual proceeds

of the Golden Crescent drug trade (between 100 and 200 billion

dollars) represents approximately one third of the Worldwide

annual turnover of narcotics, estimated by the United Nations to

be of the order of $500 billion.14

With the disintegration of the Soviet Union, a new surge in opium

production has unfolded. (According to UN estimates, the

production of opium in Afghanistan in 1998-99 -- coinciding with

the build up of armed insurgencies in the former Soviet

republics-- reached a record high of 4600 metric tons.15

Powerful business syndicates in the former Soviet Union allied

with organized crime are competing for the strategic control over

the heroin routes.

The ISI's extensive intelligence military-network was not

dismantled in the wake of the Cold War. The CIA continued to

support the Islamic "jihad" out of Pakistan. New undercover

initiatives were set in motion in Central Asia, the Caucasus and

the Balkans. Pakistan's military and intelligence apparatus

essentially "served as a catalyst for the disintegration of the

Soviet Union and the emergence of six new Muslim republics in

Central Asia." 16.

Meanwhile, Islamic missionaries of the Wahhabi sect from Saudi

Arabia had established themselves in the Muslim republics as

well as within the Russian federation encroaching upon the

institutions of the secular State. Despite its anti-American

ideology, Islamic fundamentalism was largely serving

Washington's strategic interests in the former Soviet Union.

Following the withdrawal of Soviet troops in 1989, the civil war in

Afghanistan continued unabated. The Taliban were being

supported by the Pakistani Deobandis and their political party the

Jamiat-ul-Ulema-e-Islam (JUI). In 1993, JUI entered the

government coalition of Prime Minister Benazzir Bhutto. Ties

between JUI, the Army and ISI were established. In 1995, with

the downfall of the Hezb-I-Islami Hektmatyar government in

Kabul, the Taliban not only instated a hardline Islamic

government, they also "handed control of training camps in

Afghanistan over to JUI factions..." 17

And the JUI with the support of the Saudi Wahhabi movements

played a key role in recruiting volunteers to fight in the Balkans

and the former Soviet Union.

Jane Defense Weekly confirms in this regard that "half of Taliban

manpower and equipment originate[d] in Pakistan under the ISI"

18 In fact, it would appear that following the Soviet withdrawal

both sides in the Afghan civil war continued to receive covert

support through Pakistan's ISI. 19

In other words, backed by Pakistan's military intelligence (ISI)

which in turn was controlled by the CIA, the Taliban Islamic

State was largely serving American geopolitical interests. The

Golden Crescent drug trade was also being used to finance and

equip the Bosnian Muslim Army (starting in the early 1990s) and

the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). In last few months there is

evidence that Mujahideen mercenaries are fighting in the ranks of

KLA-NLA terrorists in their assaults into Macedonia.

No doubt, this explains why Washington has closed its eyes on

the reign of terror imposed by the Taliban including the blatant

derogation of women's rights, the closing down of schools for

girls, the dismissal of women employees from government offices

and the enforcement of "the Sharia laws of punishment".20

THE WAR IN CHECHNYA

With regard to Chechnya, the main rebel leaders Shamil Basayev

and Al Khattab were trained and indoctrinated in CIA sponsored

camps in Afghanistan and Pakistan. According to Yossef

Bodansky, director of the U.S. Congress's Task Force on

Terrorism and Unconventional Warfare, the war in Chechnya had

been planned during a secret summit of HizbAllah International

held in 1996 in Mogadishu, Somalia. 21 The summit, was attended

by Osama bin Laden and high-ranking Iranian and Pakistani

intelligence officers. In this regard, the involvement of Pakistan's

ISI in Chechnya "goes far beyond supplying the Chechens with

weapons and expertise: the ISI and its radical Islamic proxies are

actually calling the shots in this war". 22

Russia's main pipeline route transits through Chechnya and

Dagestan. Despite Washington's perfunctory condemnation of

Islamic terrorism, the indirect beneficiaries of the Chechen war

are the Anglo-American oil conglomerates which are vying for

control over oil resources and pipeline corridors out of the

Caspian Sea basin.

The two main Chechen rebel armies (respectively led by

Commander Shamil Basayev and Emir Khattab) estimated at

35,000 strong were supported by Pakistan's ISI, which also

played a key role in organizing and training the Chechen rebel

army:

"[In 1994] the Pakistani Inter Services Intelligence arranged for

Basayev and his trusted lieutenants to undergo intensive Islamic

indoctrination and training in guerrilla warfare in the Khost

province of Afghanistan at Amir Muawia camp, set up in the

early 1980s by the CIA and ISI and run by famous Afghani

warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. In July 1994, upon graduating from

Amir Muawia, Basayev was transferred to Markaz-i-Dawar

camp in Pakistan to undergo training in advanced guerrilla tactics.

In Pakistan, Basayev met the highest ranking Pakistani military

and intelligence officers: Minister of Defense General Aftab

Shahban Mirani, Minister of Interior General Naserullah Babar,

and the head of the ISI branch in charge of supporting Islamic

causes, General Javed Ashraf, (all now retired). High-level

connections soon proved very useful to Basayev.23

Following his training and indoctrination stint, Basayev was

assigned to lead the assault against Russian federal troops in the

first Chechen war in 1995. His organization had also developed

extensive links to criminal syndicates in Moscow as well as ties

to Albanian organized crime and the Kosovo Liberation Army

(KLA). In 1997-98, according to Russia's Federal Security

Service (FSB) "Chechen warlords started buying up real estate in

Kosovo... through several real estate firms registered as a cover

in Yugoslavia" 24

Basayev's organisation has also been involved in a number of

rackets including narcotics, illegal tapping and sabotage of

Russia's oil pipelines, kidnapping, prostitution, trade in

counterfeit dollars and the smuggling of nuclear materials (See

Mafia linked to Albania's collapsed pyramids, 25 Alongside the

extensive laundering of drug money, the proceeds of various illicit

activities have been funneled towards the recruitment of

mercenaries and the purchase of weapons.

During his training in Afghanistan, Shamil Basayev linked up with

Saudi born veteran Mujahideen Commander "Al Khattab" who

had fought as a volunteer in Afghanistan. Barely a few months

after Basayev's return to Grozny, Khattab was invited (early

1995) to set up an army base in Chechnya for the training of

Mujahideen fighters. According to the BBC, Khattab's posting to

Chechnya had been "arranged through the Saudi-Arabian based

[International] Islamic Relief Organisation, a militant religious

organisation, funded by mosques and rich individuals which

channeled funds into Chechnya".26

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Since the Cold War era, Washington has consciously supported

Ousmane bin Laden, while at same time placing him on the FBI's

"most wanted list" as the World's foremost terrorist.

While the Mujahideen are busy fighting America's war in the

Balkans and the former Soviet Union, the FBI --operating as a

US based Police Force- is waging a domestic war against

terrorism, operating in some respects independently of the CIA

which has --since the Soviet-Afghan war-- supported

international terrorism through its covert operations.

In a cruel irony, while the Islamic jihad --featured by the Bush

Adminstration as "a threat to America"-- is blamed for the

terrorist assaults on the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon,

these same Islamic organisations constitute a key instrument of

US military-intelligence operations in the Balkans and the former

Soviet Union.

In the wake of the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington,

the truth must prevail to prevent the Bush Adminstration together

with its NATO partners from embarking upon a military adventure

which threatens the future of humanity.

ENDNOTES

Hugh Davies, International: `Informers' point the finger at bin

Laden; Washington on alert for suicide bombers, The Daily

Telegraph, London, 24 August 1998.

See Fred Halliday, "The Un-great game: the Country that lost the

Cold War, Afghanistan, New Republic, 25 March 1996):

Ahmed Rashid, The Taliban: Exporting Extremism, Foreign

Affairs, November-December 1999.

Steve Coll, Washington Post, July 19, 1992.

Dilip Hiro, Fallout from the Afghan Jihad, Inter Press Services, 21

November 1995.

Weekend Sunday (NPR); Eric Weiner, Ted Clark; 16 August

1998.

Ibid.

Dipankar Banerjee; Possible Connection of ISI With Drug

Industry, India Abroad, 2 December 1994.

Ibid

See Diego Cordovez and Selig Harrison, Out of Afghanistan: The

Inside Story of the Soviet Withdrawal, Oxford university Press,

New York, 1995. See also the review of Cordovez and Harrison in

International Press Services, 22 August 1995.

Alfred McCoy, Drug fallout: the CIA's Forty Year Complicity in

the Narcotics Trade. The Progressive; 1 August 1997.

Ibid

Ibid.

Douglas Keh, Drug Money in a changing World, Technical

document no 4, 1998, Vienna UNDCP, p. 4. See also Report of

the International Narcotics Control Board for 1999,

E/INCB/1999/1 United Nations Publication, Vienna 1999, p

49-51, And Richard Lapper, UN Fears Growth of Heroin Trade,

Financial Times, 24 February 2000.

Report of the International Narcotics Control Board, op cit, p

49-51, see also Richard Lapper, op. cit.

International Press Services, 22 August 1995.

Ahmed Rashid, The Taliban: Exporting Extremism, Foreign

Affairs, November- December, 1999, p. 22.

Quoted in the Christian Science Monitor, 3 September 1998)

Tim McGirk, Kabul learns to live with its bearded conquerors,

The Independent, London, 6 November1996.

See K. Subrahmanyam, Pakistan is Pursuing Asian Goals, India

Abroad, 3 November 1995.

Levon Sevunts, Who's calling the shots?: Chechen conflict finds

Islamic roots in Afghanistan and Pakistan, 23 The Gazette,

Montreal, 26 October 1999..

Ibid

Ibid.

See Vitaly Romanov and Viktor Yadukha, Chechen Front Moves

To Kosovo Segodnia, Moscow, 23 Feb 2000.

The European, 13 February 1997, See also Itar-Tass, 4-5

January 2000.

BBC, 29 September 1999).

The URL of this article is:

http://globalresearch.ca/articles/CHO109C.html

Copyright Michel Chossudovsky, Montreal, September 2001. All

rights reserved. Centre for Research on Globalisation at

http://globalresearch.ca Permission is granted to post this text on

non-commercial community internet sites, provided the source

and the URL are indicated, the essay remains intact and the

copyright note is displayed. To publish this text in printed and/or

other forms, including commercial internet sites and excerpts,

contact the author at chossudovsky@..., fax:

1-514-4256224.

---

Questa lista e' curata da componenti del

Coordinamento Nazionale per la Jugoslavia (CNJ).

I documenti distribuiti non rispecchiano necessariamente

le posizioni ufficiali o condivise da tutto il CNJ, ma

vengono fatti circolare per il loro contenuto informativo al

solo scopo di segnalazione e commento ("for fair use only").

Archivio:

> http://www.domeus.it/circles/jugoinfo oppure:

> http://groups.yahoo.com/group/crj-mailinglist/messages

Per iscriversi al bollettino: <jugoinfo-subscribe@...>

Per cancellarsi: <jugoinfo-unsubscribe@...>

Per inviare materiali e commenti: <jugocoord@...>

---- Spot ------------------------------------------------------------

PERCHE' ASPETTARE UN'EVENTO PER FARE REGALI!

Vacanze, idee regalo, liste nozze...

tutte le migliori offerte direttamente

nella vostra casella di posta!

http://www.domeus.it/ad3650330/valuemail.domeus

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Per cancellarti da questo gruppo, invia un messaggio vuoto a: jugoinfo-unsubscribe@...

Subject: BELGRADE LAW PROFESSORS' VERDICT

Date: Mon, 10 Sep 2001 18:04:31 +0200

From: "Vladimir Krsljanin"

In their aggression against the law and justice, NATO&Soros

clerks in the so-called "International Criminal Tribunal for

Former Yugoslavia" based in the Hague, decided to ignore, as

essentially unpleasant for their dirty work, the initiative of

leading law experts and law professors of Belgrade University to

appear in the court room as real AMICI CURIAE (in its real

meaning - as FRIENDS OF JUSTICE) and expose monstrous

character of this institution, for long time successfully hidden

from public.

Instead, they have appointed three attorneys (from Holland,

England and Yugoslavia), proven as real FRIENDS OF (WHITE)

HOUSE, to serve as quasidefense for president Milosevic. That

way their attempted trial of president Milosevic would become

the greatest political FARCE ever seen. Belgrade professors

already condemned in press conference such illegal and absurd

decision of both "Tribunal" and those three attorneys. Accepting

such a role they should lose their licenses, Belgrade professors

stated.

For the sake of justice, the full text of the initiative of Belgrade

law professors, is hereby given.

TO THE INTERNATIONAL TRIBUNAL FOR

THE PROSECUTION OF PERSONS

RESPONSIBLE FOR SERIOUS VIOLATIONS

OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW

COMMITTED IN THE TERRITORY OF THE

FORMER YUGOSLAVIA SINCE 1991

To the Trial Chambers in all the cases before the

Tribunal

PROPOSAL FOR APPEARANCE BEFORE

TRIAL CHAMBERS BY VIRTUE OF RULE 74

ON PROCEDURE AND EVIDENCE (AMICUS

CURIAE)

The Professors and Assistant Lecturers of the

Faculty of Law of the University of Belgrade have

been following with great attention the work of the

International Tribunal for the prosecution of persons

responsible for serious violations of international

humanitarian law committed in the territory of the

former Yugoslavia since 1991, as the institution that,

by a number of elements, is new and specific and all

the more interesting therefore from the purely

theoretical standpoint and then also as an organ

whose work will strongly affect the current and

future situation in the space of our country and the

situation throughout the region. A large group of

teachers and associates of our institution has

already in the country itself taken initiatives in order

to ensure respect for the constitutionality and

legality in the field of prosecution of persons charged

with violations of international humanitarian law and

especially in the field of respect for the legal norms

concerning fundamental human rights. It is our firm

belief that the prosecution of perpetrators of criminal

offences which have violated international

humanitarian law is one of the imperatives and

prerequisites for the normalisation of relations and

for restoring stability in the space of the former

Yugoslavia just as it is the case in all regions of the

world where such offences were and are still being

committed and are regrettably a regular corollary of

virtually all wars and conflicts. However, we also

firmly believe that one cannot create law out of

non-law and that therefore when prosecuting and

trying in court even such serious offences as those

that the Tribunal has been dealing with, the rules of

international law must be strictly respected and

particularly those among them that protect

fundamental human rights and freedoms that are of a

universal nature and that as jus cogens, within the

framework of international law, have a hierarchically

superior position vis-a-vis the majority of other

rules. This action-taking in accordance with the law

is everywhere a necessity that cannot be called into

question. However, in the case of the conflicts that

took place in the past ten years or so in the former

SFRY, respect for law is all the more essential as

these were conflicts that left tragic consequences on

virtually all peoples in these parts, conflicts that

represent at the same time both the expression and

the integral part of the tragic fate of these peoples,

whose troublesome past left behind a number of

disputes and unresolved situations over which they

quarrelled and waged wars also throughout their

history and over which they continue to quarrel even

today.

Bearing in mind both the mentioned necessity of

strictly respecting law, both generally and

specifically regarding the issues related to the

conflict in the former Yugoslavia, and the huge real

importance that the Tribunal and its works have for

our country and the region, for our fate and the fate of

future generations in these parts, we consider it

important and from the standpoint of our human and

our professional conscience necessary to approach

the Tribunal and request that our representatives be

allowed by the Trial Chambers in the above

mentioned proceedings to appear in accordance with

Rule 74 on procedure and evidence before the Trial

Chambers conducting these proceedings and present

for each of these proceedings their specific

objections based on the general objections that we

shall make in this correspondence, which concern

respect of international law in the Tribunal's work

and in particular the norms protecting human rights

and fundamental freedoms.

We were prompted to take this step also by the

statement by Judge May during the first appearance

of former President Slobodan Milosevic before the

Tribunal, to the effect that the international law

would be applied to the accused in future. This would

have to mean also that in the course of proceedings

the Tribunal would respect all of his human rights,

both those prescribed by the International Covenant

on Civil and Political Rights and others. This

statement, of course, also applies to all other

indicted persons.

We wish to point out that we decided to approach the

Tribunal in this way even though we share the view

of a large number of top-ranking international legal

experts world-wide that the International Tribunal

for prosecution of persons responsible for serious

violations of international humanitarian law

committed in the territory of the former Yugoslavia

since 1991 was established in the manner contrary to

the UN Charter in support of which we shall also

present our arguments but as the Tribunal does exist

in fact as it functions and keeps in custody several

dozens of indicted persons, both Serbs and Croats

and Muslims, which from our viewpoint and from the

viewpoint of law is all the same, our professional and

human responsibility and conscience make it

incumbent upon us in this way, too, to try to

contribute to the respect of international law with

regard to all these indicted persons, no matter which

national grouping they belong to because they are all

equal before the law.

We are, likewise, of the opinion that in the interest of

law, justice and peace, it would be useful in our

region for the Tribunal's relevant Trial Chambers to

approach the Faculties of Law in Sarajevo, Zagreb

and other university centre in the space of the former

SFRY, whose scholars, whose competence we had

the opportunity to personally witness during many

years of close co-operation, also could make an

important contribution to ensuring consistent and

impartial law enforcement with respect to all the

indicted for violations of international humanitarian

law. For our part, we have been prompted to

approach the Tribunal in this manner also by the fact

that unlike the state authorities from other states

formed in the space of the former SFRY that care for

the status and rights of their citizens being held on

trial at the Tribunal, as well as for the dignity of their

own state and peoples living in it, our state

authorities do not perform their duty with respect to

their citizens and their country but, as a rule, are

doing precisely the opposite. Nevertheless, we wish

by our remarks and suggestions to promote justice

and respect for law, also relative to the citizens of

other states from the region, believing it to be our

duty to adopt a strictly professional attitude on this

plane as well and treat all equally.

In the text below, we shall present (I) our view of the

legal validity of the acts establishing the Tribunal,

but would not discuss that topic further, since the

Tribunal actually exists and tries people and that in

these proceedings in every case international law

should be observed; as well as (II) our general

observations regarding the set-up and the works of

the Tribunal, which our representatives would

present in more specific terms on each individual

case if the relevant Trial Chambers would grant

permission for appearance in the proceedings in the

amicus curiae capacity.

I.ABSENCE OF LEGAL GROUNDS FOR

ESTABLISHING THE HAGUE

TRIBUNAL IN THE SECURITY

COUNCIL ACTS

The Criminal Tribunal for the Former

Yugoslavia was established by UN Security

Council resolutions 808/93 and 827/93 and, as

explicitly stated in these acts, in accordance

with Chapter VII of the UN Charter.

However, the legal grounds of the acts

establishing the Tribunal, can be challenged,

i.e. it can be noted with full certainty that the

aid Security Council resolutions were

adopted in contravention of the UN Charter.

The Tribunal's establishment is legally

problematic, i.e. contrary to the valid rules of

international law and primarily the UN

Charter, on several grounds.

To start with, the Security Council is the UN

executive organ responsible for taking care

of peace and security world-wide and as

such it may not establish judicial organs. It

has the right to establish its subsidiary

organs (Article 29 of the Charter stipulates:

"The Security Council may establish such

subsidiary organs as it deems necessary for

the performance of its functions"), but as it

itself has no right to perform any judicial

unction, it cannot transfer to its subsidiary

organ any powers that it does not hold (and

within the powers it has, it may not transfer

to its subsidiary organs the decision-making

right, because this is the Security Council's

xclusive right that is exercised according to a

strictly prescribed procedure). This

interpretation is also confirmed by Article 28

of the Rules of Procedure of the Security

Council adopted on 24 June 1946 based on

Article 30 of the Charter (that is still, even

after 55 years, called "Provisional Rules of

Procedure"). This Article of the Rules of

Procedure reads as follows: "The Security

Council may appoint a commission, a

committee or a rapporteur for a specific

question". A year after the adoption of the

Charter, the Security Council, where the

representatives of the key UN founding

members played a dominant role, notably

important figures such as Ernest Bevine,

eorges Bidault, Joseph Paul-Boncour,

Edward R. Stetinius Jr., Andrei Y.

yshinsky, Andrei A. Gromyko, etc. that may

virtually be considered the Charter's

authentic interpreters, thus interpreted in the

mentioned way which subsidiary organs the

Security Council might have.

In addition, the Security Council's

competence under Article 24 of the UN

Charter is the following:

"1. In order to ensure prompt and effective

action by the United Nations, its members

confer on the Security Council primary

esponsibility for the maintenance of

international peace and security and agree

that, in carrying out its duty under this

responsibility, the Security Council acts on

their behalf.

2. In discharging these duties, the Security

Council shall act in accordance with the

purposes and principles of the United

Nations."

As part of the thus defined function, the

Security Council's key task is to take care of

respect for the principle set forth in Article 2,

item 4 of the Charter, according to which:

"All Members shall refrain in their

nternational relations from the threat or use

of force against the territorial integrity or

political independence of any state or in any

other way inconsistent with the purposes of

the United Nations." In case this principle is

violated, i.e. that there is "a threat to peace,

violation of peace or aggression" (Article 39

of the Charter), the Security Council may

ecide on the implementation of measures

(diplomatic, economic-financial and

ilitary), that must be based on Chapter 7 of

the UN Charter and whose aim it is to

maintain or restore peace and security in the

world. In international law, i.e. the part of it

concerning war and peace, there is a

traditional division into the rules concerning

the right to war (jus ad bellum) and the rules

regulating the rules of warfare, therefore,

those that are applied when the war has

already broken out in order for the war as an

otherwise inhumane phenomenon, to be made

as humane as possible, i.e. to alleviate the

orrors (this is about the so-called right in

war - jus in bello). With its above mentioned

role of taking care of peace and security in

the world, i.e. of respecting the ban on the

threat of force and the use of force, the

ecurity Council is an organ that looks after

the implementation of the rule jus ad bellum.

International criminal law, for its part, has as

its aim, primarily to prevent and punish

criminal behaviour during war conflicts, i.e. it

aims at humanising warfare, i.e. primarily

falls under the framework of "the law in

war"- "jus in bello". Of the criminal offences

within the framework of international law, it

is only the so-called "crimes against peace"

fall within the framework of "jus ad bellum",

i.e. it is only by these criminal offences that

the rules within the framework "jus ad

ellum" are violated, while all other criminal

offences fall within the framework of "jus in

bello". The Statute of The Hague Tribunal

tipulates that this Tribunal shall try virtually

all offences within the framework of

international criminal law except crimes

against peace, i.e. all the offences with the

exception of those directed against peace

and security in the world. Therefore, of all

international criminal offences, The Hague

ribunal does not deal only with those

offences that violate the values for whose

preservation the Security Council is

responsible (but, the Security Council does

not ensure the preservation of those values

through any judicial but through its executive

function). Consequently, the Criminal

Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, through

its judicial function, does not prevent

recisely the offences that violate the values

for whose protection the Security Council is

responsible, meaning that the aims that it has

to attain and the aims of the Security Council

whose subsidiary organ it is, are not the

ame.

It follows that the Security Council was not

authorised to establish the Tribunal neither

from the standpoint of the nature of its

unction nor from the standpoint of the aims

that it aspires to fulfil.

In addition to the above mentioned, the

International Criminal Tribunal for the former

Yugoslavia, is a Tribunal only for crimes

ommitted in a particular space, i.e. in the

territory of several states formed following

their secession from the former Yugoslavia.

In addition to this Tribunal, such a tribunal

exists only for Rwanda. On the other hand,

the criminal offences of the same nature

were committed and are being committed in

ar-torn areas the world over. It is not only

that selective justice cannot be considered

true justice, but this selectively established

justice also contravenes the principle of

sovereign equality of states proclaimed in

rticle 2, item 1 of the UN Charter.

In support of the above arguments, we shall

recall the indubitable authority of Professor

Mohammed Bedjaoui, President of the

nternational Court of Justice. In his book

"The new world order and the control of the

legality of the Security Council acts"

("Nouvel ordre mondiale et controle de la

legalite des actes du Conseil de Securite",

Bruxelles, 1994), he included in the eight

Security Council resolutions that he

onsidered legally most disputable and that

would, as such, be the first to be subjected to

control, also the two mentioned resolutions

on the establishment of the ad hoc Tribunal

for the former Yugoslavia - resolutions

808/93 and 827/93.

The only legally valid way in which an

international war crimes tribunal may be

established is the one resorted to in Rome in

1998, when the Statute was adopted of the

Permanent International Criminal Court of a

general jurisdiction. Regrettably, this Statute

has not yet come into force due to the

insufficient number of instruments of

ratification.

Since the Security Council is a political organ

and since its decisions are of a political

nature and given that in international law it is

considered legitimate and permissible for the

states to oppose the implementation of

political decisions taken by international

organisations, including the UN, that are

unlawful, it may be possible to conclude that

the mentioned Security Council resolutions

whereby the Tribunal was established do not

create legally valid obligations from the

standpoint of international law and law in

general. With respect to the UN Security

Council, this conclusion stems from Article

25 of the UN Charter, which reads as

follows: "The members of the United Nations

agree to accept and carry out the decisions

of the Security Council in accordance with

the present Charter." In its advisory opinion

of 21 June 1971 (in the case of the legal

consequence of the protracted presence of

South Africa in Namibia despite Security

Council resolution 276/1970), the

International Court of Justice confirmed that

the states are not duty-bound to accept and

implement the Security Council decisions

that are not in accordance with the Charter,

which would, by the way, be clear by itself

even if it were not written anywhere.

Nevertheless, as we have already noted,

despite the mentioned objections related to

the legal grounds of the Tribunal's

establishment, we have decided to request

that our representatives be allowed to appear

before the Trial Chambers in all the

mentioned cases in accordance with Rule 74

on Procedure and Evidence. We proceed

from the fact that the Tribunal exists and

unctions and from our wish for international

law to be respected in all the mentioned

proceedings.

II.THE SET-UP AND WORK OF THE

HAGUE TRIBUNAL IS CONTRARY TO

INTERNATIONAL LAW PRIMARILY

IN THE FIELD OF HUMAN RIGHTS

What poses a particular problem when the Hague

Tribunal is concerned is the fact that both its set-up

and the method of work are, to a considerable extent,

contrary to a number of rules in international law,

particularly those in the field of human rights and

fundamental freedoms. Especially important among

these rights are those stipulated in the International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, adopted and

open for signature by UN General Assembly

resolution 2200A (XXI) of 16 December 1966, that

took effect on 23 March 1976, as one of the central

documents adopted internationally. The Tribunal's

rules are often contrary also to the general legal

principles as recognized by the civilized nations and

particularly the general principles of criminal,

substantive and procedural law having universal

value (legality of sanctions, two-instance court

proceedings, division of legislative and judicial

functions, etc.). It is also noteworthy that the Hague

Tribunal works also in contravention of a number of

provisions of the European Convention on Human

Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, as well as the

practice of the European Court of Human Rights.

Finally, a number of Rules of Procedure and Evidence

as well as a number of practical procedures before

the Tribunal run counter to the rules of the indicted

person prescribed in Article 21 of the Tribunal's

Statute that correspond to the rules stipulated in

Article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and

Political Rights, so that our remarks concerning

respect for Article 14 of the Covenant as a rule also

apply to respect for Article 21 of the Statute.

Mentioned below are just some of the most important

violations of international law that appear in the

Tribunal's set-up plan and in its works.

1.Legislative and judicial functions are mixed

The Tribunal appears both as a legislative

and as a judicial body. The judges write the

Rules of Procedure and Evidence themselves

and are authorised to amend them (Article 15

of the Statute titled "Rules of Procedure and

Evidence" stipulates: "The judges of the

International Tribunal shall adopt the Rules

of Procedure and Evidence for work pending

trial, for the conduct of court proceedings and

appellate proceedings, for the acceptance of

vidence, for the protection of victims and

witnesses, as well as for other relevant

issues". They, therefore, both make law and

apply it.

The Rules of Procedure and Evidence are

frequently amended. In eight years of the

Tribunal's existence, it developed eighteen

amendments to the Rules. Such frequent

amendments of the Rules lead to legal

insecurity.

The legal insecurity and inadequacy of the

Rules of Procedure and Evidence is also

augmented by the fact that right from day one

they represented a mixture of different

systems and that their interpretation often

argely depends on the judge that is applying

them and particularly on the legal system and

tradition in the framework of which he was

trained. Such a nature of the rules and their

too frequent amendments make it impossible

to establish a stable court practice. As a

result, neither the defence nor the

rosecutors nor the judges themselves are

able to fully follow and master this practice.

What additionally undermines legal security

is also the fact that the English and the

French versions of the Rules do not always

coincide as well as the fact that with respect

to some issues, there is a discrepancy

etween the Rules and the Statute (which is

an act superior to the Rules) so that the