Informazione

This email is being sent on behalf of jaredi@...

as part of the list "emperorsclothes", that you joined.

URL: http://www.emperors-clothes.com

------------------------------------------------------------

The URL for this article is

http://emperors-clothes.com/articles/cavoski/c-4.htm

www.tenc.net

[Emperor's Clothes]

UNJUST FROM THE START, PART IV: LEARNING FROM THE INQUISITION

By Dr. Kosta Cavoski

[Part IV concludes this series of articles on the War Crimes Tribunal by

Professor Cavoski, the distinguished Yugoslav law scholar.]

MASKED WITNESSES

When in the medieval age the Inquisition wanted to protect an important

witness who was ready to testify that he/she had seen a suspect

communicating with the devil the witness was allowed to appear in court

with a mask, or hood, over the face. This was how the court heard the

"truth", and the witness was protected from the evil eye of the witch

who might take revenge after being burned at the stake.

In its fervent desire to protect the victims and witnesses of war crimes

in the former Yugoslavia from the [Serbian] devil, the makers of the

Rules of Procedure and Evidence similarly undertook to disguise the

identity of these victims and witnesses.

Thus, according to Rule 69 "in exceptional circumstances, the Prosecutor

may apply to a Trial Chamber to order the non-disclosure of the identity

of a victim or witness who may be in danger or at risk until such a

person is brought under the protection of the Tribunal. This type of

temporary concealment of a victim's or witnesses' identity can be

understood, especially as paragraph (C) of this Rule stipulates that

"the identity of the victim or witness shall be disclosed in sufficient

time prior to the trial to allow adequate time for preparation of the

defense".

What should not have been allowed under any circumstances was the

permanent concealment of the identity of victims or witnesses, neither

the allowing of a witness to refuse to answer a question on "grounds of

confidentiality". This is foreseen in Rule 70 paragraphs (B), (C) and

(D). Inasmuch as the Prosecutor obtains information given to him on

condition it remains confidential he can not disclose its source without

the agreement of the person or entity (15) who supplied it. This would

not be so unusual if such information were not used as evidence at the

trial. But the Prosecutor, with the consent of the person or

representative of an entity, may decide to use documents and other

material obtained in this way as evidence at the trial. In this case -

and this is indeed something very new - "the Trial Chamber may not order

either party to produce additional evidence received from the person or

entity providing the initial information, nor may the Trial Chamber, for

the purpose !

of obtaining such additional evidence itself summon that person or a

representative of that entity as a witness or order their attendance".

Still, the Prosecutor may call as a witness a person or entity that has

offered confidential information, but the Trial Chamber may not compel

the witness to answer any question the witness declines to answer on the

grounds of confidentiality.

One can ask what kind of witness gives the Prosecutor confidential

information and then refuses to answer further questions as to how such

information was obtained when the Trial Chamber has no right to insist.

As a rule they are undercover agents who have been operating illegally

in foreign countries in order to collect information that can not be

obtained by regular means. They are also governmental representatives

who have provided The Hague Tribunal with confidential information on

condition that it conceal the source of the information as well as the

manner in which it was obtained. The only remaining question is whether

such "evidence" can be accepted as valid or such clandestine "witnesses"

believed at all.

Another innovation that was introduced by the makers of the Rules was

testimony without the obligation to appear at the trial. According to

Rule 71, at the request of either party, the Trial Chamber "may, in

exceptional circumstances and in the interest of justice, order a

deposition be taken for use at trial and appoint for that purpose, a

Presiding Officer". Naturally, it sometimes happens that an important

witness, for health reasons, is unable to leave his home or hospital to

attend a trial. But in such cases a hearing, under the presidency of the

judge, is held in the witness' room where the witness answers the

questions of the prosecution and defense. Allowing a court officer to

take a deposition on his own whenever the Trial Chamber considers it to

be "in the interest of justice", increases the possibility of abuse and

prevents the confrontation of witnesses testifying differently about the

same subject.

The greatest "innovations" introduced by the Rules was the permanent

concealment of the identity of witnesses, victims or anyone related to

or associated with them. Under the guise of preserving privacy and

protecting a witness or victim, according to Rule 75 a judge or trial

chamber can, at a session in camera [i.e., a closed session], take:

"measures to prevent disclosure to the public or the media of the

identity or whereabouts of a victim or a witness, or of persons related

to or associated with him by such means as:

a) expunging names and identifying information from the Chamber's public

record;

b) non-disclosure to the public of any records identifying the victim;

c) giving the testimony through image - or voice-altering devices or

closed circuit television and

d) assignment of a pseudonym."

Even this was not enough for the makers of these Rules and so they added

the possibility of closed sessions and appropriate measures to

facilitate the testimony of vulnerable victims and witnesses, such as

one-way closed circuit television.

JUDICATURE WITHOUT SOVEREIGNTY

There is no doubt whatsoever that the measures for the protection of a

witness which the Holy Inquisition was capable of offering were a

child's game compared to those provided by the Ruler of The Hague

Tribunal. The Inquisition was only able to offer a frightened witness

the possibility to enter the court by a side door under cover of night

and with a hood over the head. Possibly, and very probably, the

Inquisition would have taken the same measures as The Hague Tribunal

Rules had it been able to use the technology at the disposal of The

Hague judges today.

So as to understand more easily the "singularity" and also the

exceptional possibilities of violation of the aforementioned measures

for protecting a victim or witness, we will present a hypothetical

example. Let us suppose that in an American city with disturbed and very

strained inter-racial relations the sexual assault of a member of one

race group by a member of another takes place. Terrified by the possible

revenge of the relations and neighbors of the attacker, the victim asks

the court to be allowed to testify under a pseudonym using image- and

voice- altering devices. Would the American court allow this? Certainly

not. And one of the reasons would be that such "testimony" would prevent

a fair trial.

After such a convincing example, it is necessary to ask the following

question. Why can American courts refuse this type of testimony and The

Hague Tribunal accepts it when both are concerned with the protection of

a victim or witness from possible reprisal by the accused, his relatives

or friends? The answer is surprising: the American court firmly believes

that the American judicature, including the police, is capable of

offering such protection. And as a rule it is, except in the rare cases

of organized crime. The Hague Tribunal is well aware that it is not up

to this and justifiably assumes that the so-called international

community, as embodied by the Security Council, has no intention

whatsoever of protecting any victim or witness from the Balkan cauldron.

So, if no-one is ready to protect the victims or witnesses, then at

least their identity can be hidden.

Had they taken one more step in forming this judgment, the Hague judges

would have had to ask themselves whether, under such conditions, they

should have taken on the job of judging at all if in order to protect

victims and witnesses they had to use measures that were implemented by

the Holy Inquisition. Had they any idea of the concept of sovereignty,

they would have asked the Security Council how it thought they could

take to court anyone if they were unable to provide the conditions

necessary for the execution of judicature. When in his famous work

"Leviathan" Thomas Hobbes demonstrated the essential traits of

sovereignty, he included

"the Right of Judicature, that is to say, of hearing and deciding all

Controversies which may arise concerning Law, either Civil or Natural or

concerning Fact".(16)

In the execution of judicature it is most important that sovereignty

provides general and complete protection of all subjects from injustice

by others. Because otherwise

"to every man remainth, from the natural and necessary appetite of his

own conservation, the right of protecting himself by his private

strength, which is the condition of War, and contrary to the end for

which every Common-wealth is instituted".(17)

In other words, he who would judge and is able to do so, is sovereign;

and as sovereign is bound to offer all subjects staunch protection from

violence and the injustice of others. Who is unable of offering the

second should not stand in judgment because he is not sovereign. The

members of the Security Council, particularly the permanent members,

wanted the first - to judge - without being capable of providing the

second - reliable protection. This resulted in the concealment of the

victims' and witnesses' identities and other measures as a clumsy

attempt to achieve what must be provided by a well instituted and

effective sovereign power.

Due to these important failings on the part of the Security Council and

The Hague Tribunal, a whole series of other unusual regulations to the

ridicule and shame of this Tribunal and its founders were created.

Particularly characteristic is Rule 99 which allows the arrest of a

suspect who has been acquitted. Truly a contradiction! However, this

contradiction came about for practical reasons. When the jury of an

American court of first instance brings a verdict of not guilty the

accused leaves the court room a free man, able to go where he will. The

prosecution can, of course, appeal against the first instance verdict

but it can not demand that an acquitted person stay in detention until a

second instance verdict is given. Sometimes the second instance court

revokes the first instance verdict and demands a retrial. Since the

suspect is free it may happen that he will not answer a summons by the

first instance court This, however, does not cause much worry as it is

assumed that !

the police, as an organ of sovereignty, must be capable of carrying out

every court order and bringing the person in question to trial.

The judges of The Hague Tribunal know very well although they are unable

to admit this publicly, that their sovereignty applies only to the court

room in which they judge and the prison where witnesses, suspects and

the accused are held. This forced them to make these contradictory

rules. In paragraph (A) of Rule 99, they stipulate that "in case of

acquittal the accused shall be released immediately". Then in paragraph

(B) they recant this rule by allowing the Trial Chamber, at the mere

hint of the Prosecutor submitting an appeal to "issue a warrant for the

arrest of the accused to take effect immediately". Thanks to this

sophistry, the accused can be freed and arrested at one stroke. Had The

Hague judges the ability to think logically, they would have otherwise

formulated the rule applied here: the Prosecutor shall decide on the

freeing or detaining of a person acquitted by a first instance Trial

Chamber. Truly in the spirit of the aforesaid Ottoman proverb: "The Cadi

prosecu!

tes, and the Cadi sentences".

To those well acquainted with constitutional and criminal law the rule

that allows for a witness to testify against himself is a real surprise.

Modern criminal law explicitly forbids this and a witness can refuse to

answer incriminating questions. For a long time this important legal

guarantee has been represented by the Fifth Amendment of the US

Constitution of 1787 whereby "no person .... shall be compelled in any

criminal case to be a witness against himself ".

The authors of The Hague Tribunal Rules did not pay much attention to

this great example and wrote Rule 90 paragraph (E) which allows for

forced self-incrimination:

"A witness may object to making any statement which might tend to

incriminate him. The Chamber may, however, compel the witness to answer

the question. Testimony compelled in this way shall not be used as

evidence in a subsequent prosecution against the witness for any offense

other than perjury".

It is worthwhile asking why the rule makers allowed for the forced

self-incrimination of a witness if such evidence would not be used

against him. They were probably presuming that war crimes are most often

carried out by groups of people who, if they are forced to do so, will

implicate each other. Supposing The Hague Tribunal had the opportunity

of imprisoning two persons suspected of committing the same war crime

without either knowing the fate of the other. One could be forced to

testify against the other with the assurance that his testimony would

not be used against him, and vice versa. In this way the Prosecutor can

obtain evidence against them both without there formally having been any

self- incrimination. To our great surprise the rule makers were very

perfidious in this matter, with no concern for the fact that their

resourcefulness and ingeniousness was in direct contradiction to the

principle of modern criminal law that self-incriminating cannot be

exacted.

Finally, the above mentioned rules contain a series of undefined

concepts which allow for whimsicality and caprice. A characteristic

example is given by Rule 79 which permits the exclusion of the media and

public from court proceedings or part of the proceedings for the

following reasons:

1) public order or morality;

2) safety, security or non-disclosure of the identity of a victim or

witness, or

3) the protection of the interests of justice.

In a well founded legal system only public order and morality are

considered to be valid reasons for the partial or complete exclusion of

the public from court proceedings, and this only under strictly defined

circumstances. The secrecy of court proceedings through concealment of

the identity of a victim or witness is inadmissible, as already shown,

while the "interests of justice" as a reason for the exclusion of the

public, is yet another innovation whereby The Hague Tribunal "enriched"

legal theory and practice. Justice is the supreme legal value and since

law and judicature exist for the realization of justice, the provision

of "interests of justice" as one of the reasons for the exclusion of the

public was done in order to create a blanket discretionary norm which

would allow the Trial Chamber to do what it wanted under the umbrella of

expediency. The term was also introduced as an excuse for the taking of

depositions for later use at a trial (Rule 71 paragraph A) and acc!

eptance of evidence of a consistent pattern of conduct relevant to

serious violations of international humanitarian law (Rule 93 paragraph

A).

Finally, Prosecutor Richard Goldstone did not want to miss the chance of

possibly using or abusing the very elastic norms containing the loose

term "interests of justice". This is why he included in the regulations

regarding his own power (being his own legislator), the stipulation that

in certain circumstances he could grant any concessions to persons who

participated in alleged offenses in order to secure their evidence in

the prosecution of others (for example, by refraining from prosecuting

an accomplice in return for the testimony of the accomplice against

another offender), and that this "may be appropriate in the interests of

justice".(18) He hereby made it known that he would be acting on his own

will and not in his official capacity, and that certain executors of

alleged crimes could be acquitted in return for cooperation, i.e. if

they were willing to blame their accomplices. This kind of trade-off was

what he called justice.

"THE JUSTICE WHICH IS NOT SEEN TO BE DONE"

Justice is taken to infer a certain type of equality, primarily an

elementary equality before the law. It would appear that the members of

the Security Council knew this when they introduced the following

regulation into the Statute of the International Tribunal:

"All persons shall be equal before the International Tribunal" (article

21, paragraph l).

This kind of equality is taken to mean that all detained persons at The

Hague have exactly the same conditions of detention and that no

exceptions will be made. However, The Hague Tribunal judges believed

that justice was what they thought it to be, and so they introduced into

their rules a regulation allowing for important differences in the

conditions of detention. According to Rule 64

"the President of the Tribunal may, on the application of a party,

request modification of the conditions of detention of an accused".

This is as if a Mafia boss in the US were to request of the judge

responsible for trying his case that he be allowed to await trial in his

own villa from where he had previously carried out his "business" on

condition he pay from his own pocket a prison guard to prevent him from

absconding.

However paradoxical this example may seem, this is what happened at The

Hague. While the terminally ill Serb General Djordje Djukic was interned

in a prison cell without adequate medical care, the Croat General

Tihomir Blaskic, through his powerful patrons, made a deal with the

Tribunal President that he await trial in a luxurious villa surrounded

by guards paid by his "friends", instead of in prison. According to

Antonio Cassese this was done in the interests of justice - the kind of

"justice" whereby it is easy "to be a cardinal if your father is the

pope".

There is an English saying: "Justice has not only to be done, but it has

to be seen to be done". What could be seen at The Hague was not justice

but caprice and injustice.

***

Footnotes

(15) Being a state, one of its institutions or some organization.

(16) Thomas Hobbes, "Leviathan", edited by C.B. Macpherson,

Harmondsworth. Penguin Books 1982, p. 234

(17) Ibid.

(18) Regulation No. 1 of 1994, as amended 17 May 1995.

***

We get by with a little help from our friends...

We receive all our funding from individuals like you, that is, from

people who have a critical attitude toward the Official Truth. We would

like everyone to read Emperor's Clothes whether they can afford to

contribute financially or not, but if you can make a contribution,

please do. Recently we were shut down for almost a week by a hacker. We

are taking steps to improve our security and also to increase the number

of people who hear about Emperor's Clothes. These improvements cost

money.

Small contributions help and so do big ones.

To make a donation, please mail a check to Emperor's Clothes, P.O. Box

610-321, Newton, MA 02461-0321. (USA)

Or click here to use our secure server.

Or call 617 916-1705 between 9:30 AM and 5:30 PM, Eastern Time (USA) and

ask for Bob. He we will take your credit card information over the

phone.

Thanks for reading Emperor's Clothes.

www.tenc.net

[Emperor's Clothes]

---

Bollettino di controinformazione del

Coordinamento Nazionale "La Jugoslavia Vivra'"

I documenti distribuiti non rispecchiano necessariamente le

opinioni delle realta' che compongono il Coordinamento, ma

vengono fatti circolare per il loro contenuto informativo al

solo scopo di segnalazione e commento ("for fair use only")

Per iscriversi al bollettino: <jugoinfo-subscribe@...>

Per cancellarsi: <jugoinfo-unsubscribe@...>

Contributi e segnalazioni: <jugocoord@...>

Sito WEB : http://digilander.iol.it/lajugoslaviavivra

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Una newsletter personale,

un forum web personale,

una mailing list personale, ...?

Gratis sotto

http://www.ecircle.it/ad201158/www.ecircle.it

as part of the list "emperorsclothes", that you joined.

URL: http://www.emperors-clothes.com

------------------------------------------------------------

The URL for this article is

http://emperors-clothes.com/articles/cavoski/c-4.htm

www.tenc.net

[Emperor's Clothes]

UNJUST FROM THE START, PART IV: LEARNING FROM THE INQUISITION

By Dr. Kosta Cavoski

[Part IV concludes this series of articles on the War Crimes Tribunal by

Professor Cavoski, the distinguished Yugoslav law scholar.]

MASKED WITNESSES

When in the medieval age the Inquisition wanted to protect an important

witness who was ready to testify that he/she had seen a suspect

communicating with the devil the witness was allowed to appear in court

with a mask, or hood, over the face. This was how the court heard the

"truth", and the witness was protected from the evil eye of the witch

who might take revenge after being burned at the stake.

In its fervent desire to protect the victims and witnesses of war crimes

in the former Yugoslavia from the [Serbian] devil, the makers of the

Rules of Procedure and Evidence similarly undertook to disguise the

identity of these victims and witnesses.

Thus, according to Rule 69 "in exceptional circumstances, the Prosecutor

may apply to a Trial Chamber to order the non-disclosure of the identity

of a victim or witness who may be in danger or at risk until such a

person is brought under the protection of the Tribunal. This type of

temporary concealment of a victim's or witnesses' identity can be

understood, especially as paragraph (C) of this Rule stipulates that

"the identity of the victim or witness shall be disclosed in sufficient

time prior to the trial to allow adequate time for preparation of the

defense".

What should not have been allowed under any circumstances was the

permanent concealment of the identity of victims or witnesses, neither

the allowing of a witness to refuse to answer a question on "grounds of

confidentiality". This is foreseen in Rule 70 paragraphs (B), (C) and

(D). Inasmuch as the Prosecutor obtains information given to him on

condition it remains confidential he can not disclose its source without

the agreement of the person or entity (15) who supplied it. This would

not be so unusual if such information were not used as evidence at the

trial. But the Prosecutor, with the consent of the person or

representative of an entity, may decide to use documents and other

material obtained in this way as evidence at the trial. In this case -

and this is indeed something very new - "the Trial Chamber may not order

either party to produce additional evidence received from the person or

entity providing the initial information, nor may the Trial Chamber, for

the purpose !

of obtaining such additional evidence itself summon that person or a

representative of that entity as a witness or order their attendance".

Still, the Prosecutor may call as a witness a person or entity that has

offered confidential information, but the Trial Chamber may not compel

the witness to answer any question the witness declines to answer on the

grounds of confidentiality.

One can ask what kind of witness gives the Prosecutor confidential

information and then refuses to answer further questions as to how such

information was obtained when the Trial Chamber has no right to insist.

As a rule they are undercover agents who have been operating illegally

in foreign countries in order to collect information that can not be

obtained by regular means. They are also governmental representatives

who have provided The Hague Tribunal with confidential information on

condition that it conceal the source of the information as well as the

manner in which it was obtained. The only remaining question is whether

such "evidence" can be accepted as valid or such clandestine "witnesses"

believed at all.

Another innovation that was introduced by the makers of the Rules was

testimony without the obligation to appear at the trial. According to

Rule 71, at the request of either party, the Trial Chamber "may, in

exceptional circumstances and in the interest of justice, order a

deposition be taken for use at trial and appoint for that purpose, a

Presiding Officer". Naturally, it sometimes happens that an important

witness, for health reasons, is unable to leave his home or hospital to

attend a trial. But in such cases a hearing, under the presidency of the

judge, is held in the witness' room where the witness answers the

questions of the prosecution and defense. Allowing a court officer to

take a deposition on his own whenever the Trial Chamber considers it to

be "in the interest of justice", increases the possibility of abuse and

prevents the confrontation of witnesses testifying differently about the

same subject.

The greatest "innovations" introduced by the Rules was the permanent

concealment of the identity of witnesses, victims or anyone related to

or associated with them. Under the guise of preserving privacy and

protecting a witness or victim, according to Rule 75 a judge or trial

chamber can, at a session in camera [i.e., a closed session], take:

"measures to prevent disclosure to the public or the media of the

identity or whereabouts of a victim or a witness, or of persons related

to or associated with him by such means as:

a) expunging names and identifying information from the Chamber's public

record;

b) non-disclosure to the public of any records identifying the victim;

c) giving the testimony through image - or voice-altering devices or

closed circuit television and

d) assignment of a pseudonym."

Even this was not enough for the makers of these Rules and so they added

the possibility of closed sessions and appropriate measures to

facilitate the testimony of vulnerable victims and witnesses, such as

one-way closed circuit television.

JUDICATURE WITHOUT SOVEREIGNTY

There is no doubt whatsoever that the measures for the protection of a

witness which the Holy Inquisition was capable of offering were a

child's game compared to those provided by the Ruler of The Hague

Tribunal. The Inquisition was only able to offer a frightened witness

the possibility to enter the court by a side door under cover of night

and with a hood over the head. Possibly, and very probably, the

Inquisition would have taken the same measures as The Hague Tribunal

Rules had it been able to use the technology at the disposal of The

Hague judges today.

So as to understand more easily the "singularity" and also the

exceptional possibilities of violation of the aforementioned measures

for protecting a victim or witness, we will present a hypothetical

example. Let us suppose that in an American city with disturbed and very

strained inter-racial relations the sexual assault of a member of one

race group by a member of another takes place. Terrified by the possible

revenge of the relations and neighbors of the attacker, the victim asks

the court to be allowed to testify under a pseudonym using image- and

voice- altering devices. Would the American court allow this? Certainly

not. And one of the reasons would be that such "testimony" would prevent

a fair trial.

After such a convincing example, it is necessary to ask the following

question. Why can American courts refuse this type of testimony and The

Hague Tribunal accepts it when both are concerned with the protection of

a victim or witness from possible reprisal by the accused, his relatives

or friends? The answer is surprising: the American court firmly believes

that the American judicature, including the police, is capable of

offering such protection. And as a rule it is, except in the rare cases

of organized crime. The Hague Tribunal is well aware that it is not up

to this and justifiably assumes that the so-called international

community, as embodied by the Security Council, has no intention

whatsoever of protecting any victim or witness from the Balkan cauldron.

So, if no-one is ready to protect the victims or witnesses, then at

least their identity can be hidden.

Had they taken one more step in forming this judgment, the Hague judges

would have had to ask themselves whether, under such conditions, they

should have taken on the job of judging at all if in order to protect

victims and witnesses they had to use measures that were implemented by

the Holy Inquisition. Had they any idea of the concept of sovereignty,

they would have asked the Security Council how it thought they could

take to court anyone if they were unable to provide the conditions

necessary for the execution of judicature. When in his famous work

"Leviathan" Thomas Hobbes demonstrated the essential traits of

sovereignty, he included

"the Right of Judicature, that is to say, of hearing and deciding all

Controversies which may arise concerning Law, either Civil or Natural or

concerning Fact".(16)

In the execution of judicature it is most important that sovereignty

provides general and complete protection of all subjects from injustice

by others. Because otherwise

"to every man remainth, from the natural and necessary appetite of his

own conservation, the right of protecting himself by his private

strength, which is the condition of War, and contrary to the end for

which every Common-wealth is instituted".(17)

In other words, he who would judge and is able to do so, is sovereign;

and as sovereign is bound to offer all subjects staunch protection from

violence and the injustice of others. Who is unable of offering the

second should not stand in judgment because he is not sovereign. The

members of the Security Council, particularly the permanent members,

wanted the first - to judge - without being capable of providing the

second - reliable protection. This resulted in the concealment of the

victims' and witnesses' identities and other measures as a clumsy

attempt to achieve what must be provided by a well instituted and

effective sovereign power.

Due to these important failings on the part of the Security Council and

The Hague Tribunal, a whole series of other unusual regulations to the

ridicule and shame of this Tribunal and its founders were created.

Particularly characteristic is Rule 99 which allows the arrest of a

suspect who has been acquitted. Truly a contradiction! However, this

contradiction came about for practical reasons. When the jury of an

American court of first instance brings a verdict of not guilty the

accused leaves the court room a free man, able to go where he will. The

prosecution can, of course, appeal against the first instance verdict

but it can not demand that an acquitted person stay in detention until a

second instance verdict is given. Sometimes the second instance court

revokes the first instance verdict and demands a retrial. Since the

suspect is free it may happen that he will not answer a summons by the

first instance court This, however, does not cause much worry as it is

assumed that !

the police, as an organ of sovereignty, must be capable of carrying out

every court order and bringing the person in question to trial.

The judges of The Hague Tribunal know very well although they are unable

to admit this publicly, that their sovereignty applies only to the court

room in which they judge and the prison where witnesses, suspects and

the accused are held. This forced them to make these contradictory

rules. In paragraph (A) of Rule 99, they stipulate that "in case of

acquittal the accused shall be released immediately". Then in paragraph

(B) they recant this rule by allowing the Trial Chamber, at the mere

hint of the Prosecutor submitting an appeal to "issue a warrant for the

arrest of the accused to take effect immediately". Thanks to this

sophistry, the accused can be freed and arrested at one stroke. Had The

Hague judges the ability to think logically, they would have otherwise

formulated the rule applied here: the Prosecutor shall decide on the

freeing or detaining of a person acquitted by a first instance Trial

Chamber. Truly in the spirit of the aforesaid Ottoman proverb: "The Cadi

prosecu!

tes, and the Cadi sentences".

To those well acquainted with constitutional and criminal law the rule

that allows for a witness to testify against himself is a real surprise.

Modern criminal law explicitly forbids this and a witness can refuse to

answer incriminating questions. For a long time this important legal

guarantee has been represented by the Fifth Amendment of the US

Constitution of 1787 whereby "no person .... shall be compelled in any

criminal case to be a witness against himself ".

The authors of The Hague Tribunal Rules did not pay much attention to

this great example and wrote Rule 90 paragraph (E) which allows for

forced self-incrimination:

"A witness may object to making any statement which might tend to

incriminate him. The Chamber may, however, compel the witness to answer

the question. Testimony compelled in this way shall not be used as

evidence in a subsequent prosecution against the witness for any offense

other than perjury".

It is worthwhile asking why the rule makers allowed for the forced

self-incrimination of a witness if such evidence would not be used

against him. They were probably presuming that war crimes are most often

carried out by groups of people who, if they are forced to do so, will

implicate each other. Supposing The Hague Tribunal had the opportunity

of imprisoning two persons suspected of committing the same war crime

without either knowing the fate of the other. One could be forced to

testify against the other with the assurance that his testimony would

not be used against him, and vice versa. In this way the Prosecutor can

obtain evidence against them both without there formally having been any

self- incrimination. To our great surprise the rule makers were very

perfidious in this matter, with no concern for the fact that their

resourcefulness and ingeniousness was in direct contradiction to the

principle of modern criminal law that self-incriminating cannot be

exacted.

Finally, the above mentioned rules contain a series of undefined

concepts which allow for whimsicality and caprice. A characteristic

example is given by Rule 79 which permits the exclusion of the media and

public from court proceedings or part of the proceedings for the

following reasons:

1) public order or morality;

2) safety, security or non-disclosure of the identity of a victim or

witness, or

3) the protection of the interests of justice.

In a well founded legal system only public order and morality are

considered to be valid reasons for the partial or complete exclusion of

the public from court proceedings, and this only under strictly defined

circumstances. The secrecy of court proceedings through concealment of

the identity of a victim or witness is inadmissible, as already shown,

while the "interests of justice" as a reason for the exclusion of the

public, is yet another innovation whereby The Hague Tribunal "enriched"

legal theory and practice. Justice is the supreme legal value and since

law and judicature exist for the realization of justice, the provision

of "interests of justice" as one of the reasons for the exclusion of the

public was done in order to create a blanket discretionary norm which

would allow the Trial Chamber to do what it wanted under the umbrella of

expediency. The term was also introduced as an excuse for the taking of

depositions for later use at a trial (Rule 71 paragraph A) and acc!

eptance of evidence of a consistent pattern of conduct relevant to

serious violations of international humanitarian law (Rule 93 paragraph

A).

Finally, Prosecutor Richard Goldstone did not want to miss the chance of

possibly using or abusing the very elastic norms containing the loose

term "interests of justice". This is why he included in the regulations

regarding his own power (being his own legislator), the stipulation that

in certain circumstances he could grant any concessions to persons who

participated in alleged offenses in order to secure their evidence in

the prosecution of others (for example, by refraining from prosecuting

an accomplice in return for the testimony of the accomplice against

another offender), and that this "may be appropriate in the interests of

justice".(18) He hereby made it known that he would be acting on his own

will and not in his official capacity, and that certain executors of

alleged crimes could be acquitted in return for cooperation, i.e. if

they were willing to blame their accomplices. This kind of trade-off was

what he called justice.

"THE JUSTICE WHICH IS NOT SEEN TO BE DONE"

Justice is taken to infer a certain type of equality, primarily an

elementary equality before the law. It would appear that the members of

the Security Council knew this when they introduced the following

regulation into the Statute of the International Tribunal:

"All persons shall be equal before the International Tribunal" (article

21, paragraph l).

This kind of equality is taken to mean that all detained persons at The

Hague have exactly the same conditions of detention and that no

exceptions will be made. However, The Hague Tribunal judges believed

that justice was what they thought it to be, and so they introduced into

their rules a regulation allowing for important differences in the

conditions of detention. According to Rule 64

"the President of the Tribunal may, on the application of a party,

request modification of the conditions of detention of an accused".

This is as if a Mafia boss in the US were to request of the judge

responsible for trying his case that he be allowed to await trial in his

own villa from where he had previously carried out his "business" on

condition he pay from his own pocket a prison guard to prevent him from

absconding.

However paradoxical this example may seem, this is what happened at The

Hague. While the terminally ill Serb General Djordje Djukic was interned

in a prison cell without adequate medical care, the Croat General

Tihomir Blaskic, through his powerful patrons, made a deal with the

Tribunal President that he await trial in a luxurious villa surrounded

by guards paid by his "friends", instead of in prison. According to

Antonio Cassese this was done in the interests of justice - the kind of

"justice" whereby it is easy "to be a cardinal if your father is the

pope".

There is an English saying: "Justice has not only to be done, but it has

to be seen to be done". What could be seen at The Hague was not justice

but caprice and injustice.

***

Footnotes

(15) Being a state, one of its institutions or some organization.

(16) Thomas Hobbes, "Leviathan", edited by C.B. Macpherson,

Harmondsworth. Penguin Books 1982, p. 234

(17) Ibid.

(18) Regulation No. 1 of 1994, as amended 17 May 1995.

***

We get by with a little help from our friends...

We receive all our funding from individuals like you, that is, from

people who have a critical attitude toward the Official Truth. We would

like everyone to read Emperor's Clothes whether they can afford to

contribute financially or not, but if you can make a contribution,

please do. Recently we were shut down for almost a week by a hacker. We

are taking steps to improve our security and also to increase the number

of people who hear about Emperor's Clothes. These improvements cost

money.

Small contributions help and so do big ones.

To make a donation, please mail a check to Emperor's Clothes, P.O. Box

610-321, Newton, MA 02461-0321. (USA)

Or click here to use our secure server.

Or call 617 916-1705 between 9:30 AM and 5:30 PM, Eastern Time (USA) and

ask for Bob. He we will take your credit card information over the

phone.

Thanks for reading Emperor's Clothes.

www.tenc.net

[Emperor's Clothes]

---

Bollettino di controinformazione del

Coordinamento Nazionale "La Jugoslavia Vivra'"

I documenti distribuiti non rispecchiano necessariamente le

opinioni delle realta' che compongono il Coordinamento, ma

vengono fatti circolare per il loro contenuto informativo al

solo scopo di segnalazione e commento ("for fair use only")

Per iscriversi al bollettino: <jugoinfo-subscribe@...>

Per cancellarsi: <jugoinfo-unsubscribe@...>

Contributi e segnalazioni: <jugocoord@...>

Sito WEB : http://digilander.iol.it/lajugoslaviavivra

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Una newsletter personale,

un forum web personale,

una mailing list personale, ...?

Gratis sotto

http://www.ecircle.it/ad201158/www.ecircle.it

URL est http://emperors-clothes.com/french/articles/cent-f.htm

Cent millions pour la démocratie ?

Comment les États-Unis ont créé une opposition corrompue en Serbie

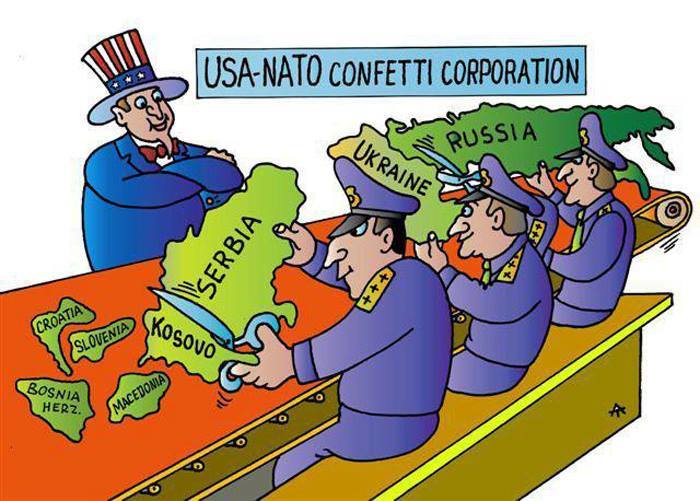

Alors que les résultats des élections en Yougoslavie défraient la

manchette, nous publions des extraits d’un texte sur l’opposition serbe

écrit par Michel Chossudovsky (Canada), Jared Israël (États-Unis), Peter

Maher (États-Unis), Max Sinclair (États-Unis), Karen Talbot (Covert

Action Quarterly des États-Unis) et Niko Varkevisser (Global Reflexion,

Pays-Bas). 15-09-2000

www.tenc.net

[Les nouveaux Habits de l'Empereur]

La coalition de l’opposition yougoslave se proclame « démocratique et

indépendante ». Toutefois, nos recherches démontrent qu’elle est

contrôlée par Washington, par les mêmes personnes qui sont intervenues

au cours des dix dernières années pour tenter de disloquer la

Yougoslavie.

Des audiences révélatrices devant le Sénat américain

En juillet 1999, le Sénat américain a tenu des audiences sur la Serbie.

L’envoyé spécial des États-Unis dans les Balkans, Robert Gelbard, son

assistant, James Pardew, et le sénateur Joseph Biden ont témoigné. Ils

ont affirmé ouvertement que les États-Unis finançaient et contrôlaient

la soi-disant opposition « indépendante et démocratique ».

La journée qui a précédé les audiences, le Sénat américain a voté cent

millions de dollars pour cette opposition. L’envoyé spécial Gelbard a

déclaré : « Au cours des deux années qui ont mené à la crise du Kosovo,

nous avons dépensé 16,5 millions $ dans différents programmes pour

soutenir la démocratisation de la Serbie. » Il a ajouté que plus de 20

millions $ ont été octroyés à Milo Djukanovic qui dirige le gouvernement

de la République yougoslave du Montenegro.

Cet argent a servi à financer, voire même créer, des partis politiques,

des stations de radio et même des syndicats. Si une puissance étrangère

avait agi de la sorte aux États-Unis, leurs agents locaux auraient été

jetés en prison.

Le témoignage de James Pardew, l’assistant de Gelbard

Pardew : « Nous sommes intervenus par le biais d’organisations non

gouvernementales. Nous avons établi un anneau autour de la Serbie

d’émissions internationales, mais nous l’offrons également aux voix

indépendantes de Serbie qui utilisent les installations internationales.

» (Remarquez l’utilisation peu usuelle de l’expression « indépendante »

qui signifie « indépendantes d’eux mais dépendantes des États-Unis ».)

Le sénateur Joseph Biden ne semble pas croire que les mesures décrites

par Pardew soient suffisantes.

Biden : « Nous pouvons rendre des installations disponibles. Mais

sommes-nous prêts à fermer les installations qui répandent de la

propagande ? »

Gelbard essaya de défendre la politique du gouvernement américain, en

soulignant que durant la guerre, l’an dernier, contre la Yougoslavie,

les États-Unis avaient effectivement « fermé » les installations de la

télévision serbe en les bombardant.

Gelbard : « Eh bien, nous avons, sénateur, au cours du conflit du

Kosovo, avec nos alliés... »

Le sénateur Biden l’interrompt, craignant que Gelbard en dise trop.

Biden : « Non, je sais cela. Je veux savoir ce qui se fait maintenant. »

Gelbard : « Eh bien, en autant que je sache, les communications n’ont

pas été rétablies entre la télévision serbe et les installations

Eutelsat et nous nous sommes assurés qu’elles seraient interrompues si

on essayait de les rétablir. »

Le sénateur Biden et l’envoyé spécial Gelbard ont eu cet échange au

sujet de l’« opposition démocratique en Serbie ».

Biden : « Que pouvons-nous faire en Serbie même ? Par exemple, Vuk

Draskovic continue à nier l’accès à Studio B, qui est supposément... »

Gelbard : « Non, il vient de donner accès à Studio B à la Radio B-92,

qui vient de rouvrir sous le nom de Radio B-292. Nous voulons que

Draskovic ouvre Studio B au reste de l’opposition et c’est le message

que nous lui acheminerons au cours des prochains jours. »

Rappelons que Gelbard était le principal conseiller de Clinton à propos

de la Yougoslavie et que Biden fait partie des principaux sénateurs

américains engagés dans l’opposition contre la Serbie. Ces deux hommes

sont tellement impliqués dans le contrôle de l’opposition « indépendante

» de la Serbie qu’ils savent – à la minute près – si Draskovic, Djindjic

et Djukanovic se partagent équitablement espace et temps d’antenne au

Studio B à Belgrade.

Soutenir un seul candidat

L’Agence France-Presse rapportait le 2 août dernier qu’une délégation de

« l’opposition démocratique » avait rencontré les dirigeants du

Montenegro pour les convaincre de soutenir le candidat de l’« opposition

démocratique » à la présidence.

« La délégation serbe comprenait Zoran Djindjic du Parti démocratique et

Vojislav Kostunica du Mouvement démocratique pour la Serbie, le candidat

pressenti pour faire face à Milosevic. »

« La rencontre eut lieu le lendemain de la rencontre de la secrétaire

d’État Madeleine Albright avec le président monténégrin Milo Djukanovic

à Rome, au cours de laquelle elle pressa de façon urgente les groupes

d’opposition à abandonner leurs menaces de boycott des élections et de

s’unir pour vaincre Milosevic. »

D’autres informations nous sont parvenues sur le voyage de Albright à

Rome et sur sa rencontre avec Djukanovic.

« En plus des échéances électorales, Albright a déclaré qu’elle avait

discuté avec Djukanovic des moyens d’accroître l’aide au Montenegro qui

est en proie à une crise économique » (Agence France-Presse, 1er août

2000). Ainsi, Albright a offert des fonds à Milo Djukanovic s’il

acceptait d’apporter son soutien à la soi-disant opposition «

indépendante ».

Au début, Djukanovic refusa. Kostunica le critiqua publiquement de ne

pas se joindre à son équipe. Puis, le 11 septembre, Djukanovic endossa

la candidature de Kostunica. Albright en a eu pour son argent.

C’est un coup de chance pour les agents américains en Yougoslavie

d’avoir réussi, en travaillant avec les gens du National Endowment for

Democracy, de manœuvrer Kostunica dans une alliance avec Djindjic et

Djukanovic et plusieurs autres sous le parapluie américain.

L’organisation de Kostunica est très faible. Sa campagne électorale

dépend des partis, groupes et médias contrôlés par les États-Unis. S’il

remporte la victoire, les marionnettes locales des États-Unis lui

fourniront le personnel étatique requis.

Le programme de l’« opposition démocratique »

L’« opposition démocratique » a fait sienne un programme rédigé par le

G-17, un groupe d’économistes néolibéraux de Belgrade, financé par le

National Endowment for Democracy. Ce programme est disponible sur les

sites web du G-17 et du « groupe étudiant » Otpor. Il comprend un

certain nombre d’items que l’« opposition démocratique » s’est engagée à

mettre en œuvre dans le cas d’une victoire aux élections présidentielles

ou dans d’autres élections. Les principaux points du programme sont les

suivants :

L’adoption du mark allemand comme monnaie pour l’ensemble de la

Yougoslavie, suivant en cela ce qui s’est fait en Bosnie, au Kosovo et

au Montenegro.

Cela aurait pour effet d’appauvrir immédiatement le peuple yougoslave en

transformant le pays en dépendance économique de l’Allemagne.

La fin du contrôle des prix. La fin des subventions pour la nourriture,

la fin des protections sociales.

Le peuple travailleur, y compris le million de réfugiés dont les

conditions sont déjà difficiles, devra acheter la nourriture aux prix

occidentaux, mais sans les salaires occidentaux.

Un traitement de choc pour transformer la Yougoslavie en pays

capitaliste sans d’abord accorder aux Yougoslaves les moyens financiers

nécessaires pour participer à une telle économie. Il en résultera la

transfert en des mains étrangères du contrôle de l’ensemble de

l’économie yougoslave. De telles applications de la soi-disant «

idéologie économique moderne » ont déjà réussi à détruire l’économie

russe.

Curieusement, le programme ne mentionne pas l’agression criminelle de

l’OTAN contre la Yougoslavie.

Le programme appelle à réduire les dépenses publiques, démilitariser et

apporter de radicales transformations au système de taxation. Toutes ces

mesures permettront à la Yougoslavie d’être contrôlée de l’extérieur.

Le programme accepte le diktat américain selon lequel la Yougoslavie

n’existe plus et que la Serbie devra se mettre à genoux devant

Washington pour être reconnue à nouveau sur la scène internationale.

Cela signifie la reddition immédiate de tous les actifs et des droits

historiques de l’État yougoslave. Ces actifs incluent des milliards de

dollars en ambassades, navires, avions, comptes de banque gelés à

travers le monde, actifs à l’étranger et propriétés accumulés par le

peuple yougoslave depuis la fin de la Première Guerre mondiale.

Le National Endowment for Democracy et le mécanisme de la subversion

Dans son témoignage, Gelbard a affirmé que le gouvernement américain

avait distribué de l’argent en Yougoslavie par l’intermédiaire d’une

soi-disant « organisation non-gouvernementale », le National Endowment

for Democracy (Fonds national pour la démocratie). Mais il ne s’agit pas

d’un organisme non-gouvernemental. Il est financé par le Congrès

américain !

Le National Endowment for Democracy a été créé en 1983 pour un but bien

précis. Tout le monde savait à ce moment-là que la CIA poursuivait les

objectifs de la politique américaine en soudoyant des gens et en mettant

sur pied des groupes bidons. Comme le souligne le Washington Post : «

Lorsque ces activités étaient révélées (ce qui était inévitable),

l’effet était dévastateur. » (22 septembre 1991)

Le Congrès américain a alors mis sur pied le National Endowment for

Democracy dans le but de faire ouvertement ce que la CIA avait

l’habitude de faire clandestinement. Il y avait là un grand avantage. La

subversion n’étant plus secrète, elle ne pouvait plus faire l’objet de

révélations !

Bénéficiant de fonds considérables, le National Endowment for Democracy

et ses filières ont commencé à recruter dans les pays ciblés des «

activistes pour la démocratie », des « activistes pour la paix » et des

« économistes indépendants ». Ces gens furent invités à festoyer dans

les plus grands restaurants et reçurent beaucoup d’argent pour leurs

comptes de dépense. On leur octroya des bourses d’études et des stages à

l’étranger. On cultiva chez eux l’idée qu’ils étaient les leaders de

demain de l’empire américain.

Ces « activistes » créèrent des « organisations indépendantes » dans

leur propre pays et sollicitèrent des fonds auprès du National Endowment

for Democracy qui, rappelons-le, les avait lui-même recrutés ! Et le

National Endowment for Democracy leur octroya les fonds demandés !

www.tenc.net

[Les nouveaux Habits de l'Empereur]

---

Bollettino di controinformazione del

Coordinamento Nazionale "La Jugoslavia Vivra'"

I documenti distribuiti non rispecchiano necessariamente le

opinioni delle realta' che compongono il Coordinamento, ma

vengono fatti circolare per il loro contenuto informativo al

solo scopo di segnalazione e commento ("for fair use only")

Per iscriversi al bollettino: <jugoinfo-subscribe@...>

Per cancellarsi: <jugoinfo-unsubscribe@...>

Contributi e segnalazioni: <jugocoord@...>

Sito WEB : http://digilander.iol.it/lajugoslaviavivra

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

eCircle ti offre una nuova opportunita:

la tua agenda sul web - per te e per i tuoi amici

Organizza on line i tuoi appuntamenti .

E' facile, veloce e gratuito!

Da oggi su

http://www.ecircle.it/ad196333/www.ecircle.it

Cent millions pour la démocratie ?

Comment les États-Unis ont créé une opposition corrompue en Serbie

Alors que les résultats des élections en Yougoslavie défraient la

manchette, nous publions des extraits d’un texte sur l’opposition serbe

écrit par Michel Chossudovsky (Canada), Jared Israël (États-Unis), Peter

Maher (États-Unis), Max Sinclair (États-Unis), Karen Talbot (Covert

Action Quarterly des États-Unis) et Niko Varkevisser (Global Reflexion,

Pays-Bas). 15-09-2000

www.tenc.net

[Les nouveaux Habits de l'Empereur]

La coalition de l’opposition yougoslave se proclame « démocratique et

indépendante ». Toutefois, nos recherches démontrent qu’elle est

contrôlée par Washington, par les mêmes personnes qui sont intervenues

au cours des dix dernières années pour tenter de disloquer la

Yougoslavie.

Des audiences révélatrices devant le Sénat américain

En juillet 1999, le Sénat américain a tenu des audiences sur la Serbie.

L’envoyé spécial des États-Unis dans les Balkans, Robert Gelbard, son

assistant, James Pardew, et le sénateur Joseph Biden ont témoigné. Ils

ont affirmé ouvertement que les États-Unis finançaient et contrôlaient

la soi-disant opposition « indépendante et démocratique ».

La journée qui a précédé les audiences, le Sénat américain a voté cent

millions de dollars pour cette opposition. L’envoyé spécial Gelbard a

déclaré : « Au cours des deux années qui ont mené à la crise du Kosovo,

nous avons dépensé 16,5 millions $ dans différents programmes pour

soutenir la démocratisation de la Serbie. » Il a ajouté que plus de 20

millions $ ont été octroyés à Milo Djukanovic qui dirige le gouvernement

de la République yougoslave du Montenegro.

Cet argent a servi à financer, voire même créer, des partis politiques,

des stations de radio et même des syndicats. Si une puissance étrangère

avait agi de la sorte aux États-Unis, leurs agents locaux auraient été

jetés en prison.

Le témoignage de James Pardew, l’assistant de Gelbard

Pardew : « Nous sommes intervenus par le biais d’organisations non

gouvernementales. Nous avons établi un anneau autour de la Serbie

d’émissions internationales, mais nous l’offrons également aux voix

indépendantes de Serbie qui utilisent les installations internationales.

» (Remarquez l’utilisation peu usuelle de l’expression « indépendante »

qui signifie « indépendantes d’eux mais dépendantes des États-Unis ».)

Le sénateur Joseph Biden ne semble pas croire que les mesures décrites

par Pardew soient suffisantes.

Biden : « Nous pouvons rendre des installations disponibles. Mais

sommes-nous prêts à fermer les installations qui répandent de la

propagande ? »

Gelbard essaya de défendre la politique du gouvernement américain, en

soulignant que durant la guerre, l’an dernier, contre la Yougoslavie,

les États-Unis avaient effectivement « fermé » les installations de la

télévision serbe en les bombardant.

Gelbard : « Eh bien, nous avons, sénateur, au cours du conflit du

Kosovo, avec nos alliés... »

Le sénateur Biden l’interrompt, craignant que Gelbard en dise trop.

Biden : « Non, je sais cela. Je veux savoir ce qui se fait maintenant. »

Gelbard : « Eh bien, en autant que je sache, les communications n’ont

pas été rétablies entre la télévision serbe et les installations

Eutelsat et nous nous sommes assurés qu’elles seraient interrompues si

on essayait de les rétablir. »

Le sénateur Biden et l’envoyé spécial Gelbard ont eu cet échange au

sujet de l’« opposition démocratique en Serbie ».

Biden : « Que pouvons-nous faire en Serbie même ? Par exemple, Vuk

Draskovic continue à nier l’accès à Studio B, qui est supposément... »

Gelbard : « Non, il vient de donner accès à Studio B à la Radio B-92,

qui vient de rouvrir sous le nom de Radio B-292. Nous voulons que

Draskovic ouvre Studio B au reste de l’opposition et c’est le message

que nous lui acheminerons au cours des prochains jours. »

Rappelons que Gelbard était le principal conseiller de Clinton à propos

de la Yougoslavie et que Biden fait partie des principaux sénateurs

américains engagés dans l’opposition contre la Serbie. Ces deux hommes

sont tellement impliqués dans le contrôle de l’opposition « indépendante

» de la Serbie qu’ils savent – à la minute près – si Draskovic, Djindjic

et Djukanovic se partagent équitablement espace et temps d’antenne au

Studio B à Belgrade.

Soutenir un seul candidat

L’Agence France-Presse rapportait le 2 août dernier qu’une délégation de

« l’opposition démocratique » avait rencontré les dirigeants du

Montenegro pour les convaincre de soutenir le candidat de l’« opposition

démocratique » à la présidence.

« La délégation serbe comprenait Zoran Djindjic du Parti démocratique et

Vojislav Kostunica du Mouvement démocratique pour la Serbie, le candidat

pressenti pour faire face à Milosevic. »

« La rencontre eut lieu le lendemain de la rencontre de la secrétaire

d’État Madeleine Albright avec le président monténégrin Milo Djukanovic

à Rome, au cours de laquelle elle pressa de façon urgente les groupes

d’opposition à abandonner leurs menaces de boycott des élections et de

s’unir pour vaincre Milosevic. »

D’autres informations nous sont parvenues sur le voyage de Albright à

Rome et sur sa rencontre avec Djukanovic.

« En plus des échéances électorales, Albright a déclaré qu’elle avait

discuté avec Djukanovic des moyens d’accroître l’aide au Montenegro qui

est en proie à une crise économique » (Agence France-Presse, 1er août

2000). Ainsi, Albright a offert des fonds à Milo Djukanovic s’il

acceptait d’apporter son soutien à la soi-disant opposition «

indépendante ».

Au début, Djukanovic refusa. Kostunica le critiqua publiquement de ne

pas se joindre à son équipe. Puis, le 11 septembre, Djukanovic endossa

la candidature de Kostunica. Albright en a eu pour son argent.

C’est un coup de chance pour les agents américains en Yougoslavie

d’avoir réussi, en travaillant avec les gens du National Endowment for

Democracy, de manœuvrer Kostunica dans une alliance avec Djindjic et

Djukanovic et plusieurs autres sous le parapluie américain.

L’organisation de Kostunica est très faible. Sa campagne électorale

dépend des partis, groupes et médias contrôlés par les États-Unis. S’il

remporte la victoire, les marionnettes locales des États-Unis lui

fourniront le personnel étatique requis.

Le programme de l’« opposition démocratique »

L’« opposition démocratique » a fait sienne un programme rédigé par le

G-17, un groupe d’économistes néolibéraux de Belgrade, financé par le

National Endowment for Democracy. Ce programme est disponible sur les

sites web du G-17 et du « groupe étudiant » Otpor. Il comprend un

certain nombre d’items que l’« opposition démocratique » s’est engagée à

mettre en œuvre dans le cas d’une victoire aux élections présidentielles

ou dans d’autres élections. Les principaux points du programme sont les

suivants :

L’adoption du mark allemand comme monnaie pour l’ensemble de la

Yougoslavie, suivant en cela ce qui s’est fait en Bosnie, au Kosovo et

au Montenegro.

Cela aurait pour effet d’appauvrir immédiatement le peuple yougoslave en

transformant le pays en dépendance économique de l’Allemagne.

La fin du contrôle des prix. La fin des subventions pour la nourriture,

la fin des protections sociales.

Le peuple travailleur, y compris le million de réfugiés dont les

conditions sont déjà difficiles, devra acheter la nourriture aux prix

occidentaux, mais sans les salaires occidentaux.

Un traitement de choc pour transformer la Yougoslavie en pays

capitaliste sans d’abord accorder aux Yougoslaves les moyens financiers

nécessaires pour participer à une telle économie. Il en résultera la

transfert en des mains étrangères du contrôle de l’ensemble de

l’économie yougoslave. De telles applications de la soi-disant «

idéologie économique moderne » ont déjà réussi à détruire l’économie

russe.

Curieusement, le programme ne mentionne pas l’agression criminelle de

l’OTAN contre la Yougoslavie.

Le programme appelle à réduire les dépenses publiques, démilitariser et

apporter de radicales transformations au système de taxation. Toutes ces

mesures permettront à la Yougoslavie d’être contrôlée de l’extérieur.

Le programme accepte le diktat américain selon lequel la Yougoslavie

n’existe plus et que la Serbie devra se mettre à genoux devant

Washington pour être reconnue à nouveau sur la scène internationale.

Cela signifie la reddition immédiate de tous les actifs et des droits

historiques de l’État yougoslave. Ces actifs incluent des milliards de

dollars en ambassades, navires, avions, comptes de banque gelés à

travers le monde, actifs à l’étranger et propriétés accumulés par le

peuple yougoslave depuis la fin de la Première Guerre mondiale.

Le National Endowment for Democracy et le mécanisme de la subversion

Dans son témoignage, Gelbard a affirmé que le gouvernement américain

avait distribué de l’argent en Yougoslavie par l’intermédiaire d’une

soi-disant « organisation non-gouvernementale », le National Endowment

for Democracy (Fonds national pour la démocratie). Mais il ne s’agit pas

d’un organisme non-gouvernemental. Il est financé par le Congrès

américain !

Le National Endowment for Democracy a été créé en 1983 pour un but bien

précis. Tout le monde savait à ce moment-là que la CIA poursuivait les

objectifs de la politique américaine en soudoyant des gens et en mettant

sur pied des groupes bidons. Comme le souligne le Washington Post : «

Lorsque ces activités étaient révélées (ce qui était inévitable),

l’effet était dévastateur. » (22 septembre 1991)

Le Congrès américain a alors mis sur pied le National Endowment for

Democracy dans le but de faire ouvertement ce que la CIA avait

l’habitude de faire clandestinement. Il y avait là un grand avantage. La

subversion n’étant plus secrète, elle ne pouvait plus faire l’objet de

révélations !

Bénéficiant de fonds considérables, le National Endowment for Democracy

et ses filières ont commencé à recruter dans les pays ciblés des «

activistes pour la démocratie », des « activistes pour la paix » et des

« économistes indépendants ». Ces gens furent invités à festoyer dans

les plus grands restaurants et reçurent beaucoup d’argent pour leurs

comptes de dépense. On leur octroya des bourses d’études et des stages à

l’étranger. On cultiva chez eux l’idée qu’ils étaient les leaders de

demain de l’empire américain.

Ces « activistes » créèrent des « organisations indépendantes » dans

leur propre pays et sollicitèrent des fonds auprès du National Endowment

for Democracy qui, rappelons-le, les avait lui-même recrutés ! Et le

National Endowment for Democracy leur octroya les fonds demandés !

www.tenc.net

[Les nouveaux Habits de l'Empereur]

---

Bollettino di controinformazione del

Coordinamento Nazionale "La Jugoslavia Vivra'"

I documenti distribuiti non rispecchiano necessariamente le

opinioni delle realta' che compongono il Coordinamento, ma

vengono fatti circolare per il loro contenuto informativo al

solo scopo di segnalazione e commento ("for fair use only")

Per iscriversi al bollettino: <jugoinfo-subscribe@...>

Per cancellarsi: <jugoinfo-unsubscribe@...>

Contributi e segnalazioni: <jugocoord@...>

Sito WEB : http://digilander.iol.it/lajugoslaviavivra

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

eCircle ti offre una nuova opportunita:

la tua agenda sul web - per te e per i tuoi amici

Organizza on line i tuoi appuntamenti .

E' facile, veloce e gratuito!

Da oggi su

http://www.ecircle.it/ad196333/www.ecircle.it

GIULIETTO CHIESA: Kostunica come Gorbaciov, o come Jeltzin? (della

serie: quelli con il vezzo di attaccare i parlamenti).

ENZO BETTIZA: Meno male che li abbiamo bombardati, e meno male che

c'e' Kostunica: adesso possiamo finalmente staccare il Kosovo! Il

tripudio del commentatore piu' antijugoslavo ed anticomunista

d'Italia.

---

LETTERA

Gorbaciov e Kostunica

GIULIETTO CHIESA

(da "Il Manifesto")

Osservando l'evolversi della situazione jugoslava (ma ormai di

Jugoslavia non è più il caso di parlare), colgo un parallelo molto

netto tra la parabola, conclusa da tempo, di Mikhail Gorbaciov e

quella, appena iniziata, di Vojislav Kostunica. Lui stesso ha

indicato, qualche giorno fa - prima del suo primo viaggio

all'estero, a Biarritz, per incontrare gli europei - i pericoli

principali ai quali è sottoposto in questa delicatissima

transizione: "i problemi maggiori me li stanno creando i miei

alleati democratici"; e: "mi auguro che dall'esterno ci lascino

tranquilli". Su entrambi i pericoli c'è l'analogia con Gorbaciov.

Dieci anni fa, l'allora presidente sovietico stava combattendo su

due fronti, esattamente come Kostunica sta facendo ora (e temo

dovrà fare sempre di più nei prossimi mesi): il primo fronte era

rappresentato dall'apparato del partito, recalcitrante a ogni

cambiamento, democratico ed economico. Il secondo fronte era

rappresentato dagli "impazienti". Un fronte largo, disorganizzato

ma influente, prevalentemente composto da intellettuali ex

comunisti. Gorbaciov fu sconfitto perché la pressione dei secondi,

affinché egli realizzasse la transizione verso l'Occidente, in

fretta, a tutti i costi, lo espose sul fianco opposto

all'offensiva degli apparati di partito. Ricordiamo che i due

fronti vennero sinteticamente definiti, dalla stampa dell'epoca,

rispettivamente come "riformatori" e "conservatori", sebbene, come

poi si vide, i primi fossero più avidi di potere e di ricchezze

che genuini riformatori. Varrà la pena di ricordare anche, ai

lettori più giovani, che Gorbaciov fu scalzato dal potere da un

colpo di stato organizzato dai "conservatori" il 18 agosto del

1991. Ma anche che - come rivelò uno dei leader "democratici"

dell'epoca, Gavrijl Popov, se non ci fosse stato il golpe di

agosto, Gorbaciov lo avrebbero gettato a mare loro, in settembre o

in ottobre. Anche Kostunica deve ora fronteggiare gli impazienti

interni. I quali sono addirittura più esigenti di quanto non lo

fossero i "democratici" russi, poiché essi ritengono - solo in

parte a ragione - di essere stati gli artefici della vittoria di

Kostunica, e chiedono di essere riconosciuti come tali. Cioè

chiedono posti, influenza, potere. E anche risarcimenti, morali e

materiali. E vogliono che Kostunica faccia i conti, in fretta e

definitivamente, con gli sconfitti, con Milosevic in primo luogo.

E' probabile che Kostunica - come a suo tempo Gorbaciov - voglia

fare molte di queste cose. Ma non tutte e, soprattutto, non in

fretta. Egli sa che la vittoria elettorale c'è stata, e grande, ma

che una parte cospicua del paese ha votato per Milosevic e non può

essere ignorata (proprio in base a considerazioni democratiche).

Egli sa bene di avere vinto le elezioni anche perché nella sua

piattaforma programmatica c'era la condanna dei bombardamenti

della Nato, c'era la difesa dell'integrità territoriale dello

Stato, c'era il rifiuto di consegnare Milosevic al tribunale

internazionale dell'Aja. Non ci fossero stati questi tre punti,

con ogni probabilità Kostunica non avrebbe vinto le elezioni.

Spingerlo a bruciare le tappe, e a smentirsi, non sarà un

suggerimento salutare: né per lui, né per la gente serba, poiché

esaspererà una transizione già di per sé molto difficile e

dolorosa. Eppure è questo che sta avvenendo. Molti interrogativi

restano dunque aperti, anche sul destino di Kostunica. L'altro

pericolo viene dall'esterno. Pochi, in Occidente, hanno fatto

autocritica sulla Russia, sebbene sia ormai evidente a tutti

(coloro che hanno un minimo di onestà intellettuale) che la

ricetta occidentale (leggi, essenzialmente, americana) per la

transizione russa verso il mercato e lo stato di diritto si sia

rivelata un terrificante fallimento. Questo spiega perché si sta

ripetendo, con Kostunica, lo stesso "errore" che si fece con

Gorbaciov, quando si pretese da lui che facesse ciò che non poteva

(e non voleva) e, visto che non seguiva i consigli dell'Occidente,

lo si scaricò e si scelse Eltsin, più corrivo, cedevole e

subalterno, ma anche più corrotto e assai meno democratico. In

base al principio: sia quello che vuole, purché faccia i nostri

interessi. Che poi quelli che Eltsin fece fossero gli interessi

dell'Occidente è ancora tutta da vedere, ma questo è un altro

discorso. Il fatto è che non si vede grande saggezza, per ora, nei

comportamenti dell'Occidente. Gli europei hanno abbracciato

Kostunica, a Biarritz, e hanno fatto bene. Ma non hanno allentato

la pressione su di lui perché concluda senza indugi l'opera di

smantellamento della Jugoslavia. Inespresso, ma tangibile, aleggia

nell'aria un ricatto: aiuti, investimenti, in cambio della resa

finale della Jugoslavia di Milosevic e, s'intende, della consegna

di Milosevic in persona. Una politica europea non c'era e continua

a non esserci dove si tratta di sapere quale sarà il destino della

Bosnia, del Kosovo, del Montenegro. E sarà cosa altamente

rischiosa, per tutti, esigere da Kostunica, semplicemente, di

comunicare ai suoi elettori che quei pezzi di terra e della loro

storia (e con essi i serbi che vi si trovano) debbono andare con

Dio.

---

Il voto nel Kosovo

I frutti di pace della guerra

"La Stampa", 1 novembre 2000

di Enzo Bettiza

Più passa il tempo, tanto più ci si rende conto che l'intervento

Nato contro la Serbia di Milosevic continua a produrre una

sequenza di risultati sempre più positivi ed efficaci. Ci si

accorge insomma che avevano torto sia i pacifisti ideologici, che

condannarono quell'intervento come un sopruso imperialistico, sia

i pacifisti conservatori che, in nome di un sofisticato realismo,

lo condannarono come un errore. Quel "sopruso" e quell'"errore"

non solo bloccarono l'ultimo tentativo di genocidio totale del

ventesimo secolo. Hanno provocato in seguito la caduta dell'ultimo

tiranno comunista europeo, hanno portato al potere a Belgrado un

nuovo presidente che sta ricucendo i legami interrotti con

l'Europa, hanno preparato il terreno per le prime elezioni

democratiche a cielo aperto in Kosovo, infine hanno assicurato la

vittoria del partito moderato di Ibrahim Rugova contro quello

estremista e militarista di Hashim Thaci. Il paventato "effetto

domino" non c'è stato. Ci sarebbe stato se l'Occidente, anziché

impegnarsi, avesse consentito ai serbi di svuotare il Kosovo e di

far esplodere la Macedonia e l'Albania con l'alluvione dei

profughi. Anche i governanti autonomisti di Podgorica stanno

traendo un sospiro, in attesa che Kostunica si decida a cambiare

la forma e la sostanza della "Federazione jugoslava"

trasformandola in una confederazione paritaria serbo-montenegrina.

C'è ancora chi continua a tracciare scenari catastrofici lasciando

immaginare che, da un'eventuale secessione kosovara, potrebbero

dipartirsi a raggiera una serie di cataclismi regionali. Non si

capisce se qui prevalga l'ignoranza o la malafede. La graduale

normalizzazione nella Serbia, nel Montenegro e nel Kosovo avviene

in un quadro generale completamente nuovo, dopo le quattro guerre

scatenate con centinaia di migliaia di morti da Milosevic e dalle

sue bande. La Slovenia è oramai un pezzo della Mitteleuropa in

procinto di superare gli esami di Maastricht. La Croazia, dopo la

scomparsa di Franjo Tudjman, non è più una "democratura" ma una

democrazia avviata a integrarsi anch'essa all'Europa. La

Bosnia-Erzegovina, dopo l'autopensionamento del presidente Alija

Izetbegovic, sta cercando un'uscita di sicurezza da un groviglio

istituzionale che di fatto vede quello Stato posticcio lacerato

tra una componente croata erzegovese, una "etnia" slavo-musulmana,

infine una confusa Repubblica serba che non si sa bene da chi sia

oggi guidata. Quanto alla Macedonia, dopo il ritiro del saggio

presidente Gligorov, essa non rappresenta affatto quel permanente

pericolo di disgregazione agitato dagli sceneggiatori del peggio:

il terzo albanese macedone è lealmente integrato nelle istituzioni

governative, amministrative ed economiche del Paese e dello Stato.

Resta, ovviamente, la questione delle questioni: l'indipendenza di

Pristina. Anche qui l'ottica prevalente è falsa. Non si tratta di

far "convivere" cinquantamila serbi spaventati con una nazione di

due milioni di albanesi la cui potenza demografica è peraltro la

più elevata in Europa. Si tratta di negoziare i ritmi di una

secessione progressiva quanto inevitabile. I balcanici, quando

sono moderati, sono anche maestri in operazioni omeopatiche del

genere. Kostunica e Rugova saranno all'altezza del compito?

------