Informazione

Inizio del messaggio inoltrato:

> Da: "Abconlus" <info @ abconlus.it>

> Data: Lun 7 Giu 2004 06:38:32 Europe/Rome

> A: ABC - A, B, C, Solidarietà e pace <abcsolidarieta @ tiscalinet.it>

> Oggetto: da ABC - Relazione viaggio in Serbia e Repubblika Sprspa

> maggio 2004

> Rispondere-A: <info @ abconlus.it>

>

> Gentili amici,

> in allegato la relazione del recente viaggio nelle Repubbliche di

> Srbja i Cerna Gora e Srpska.

> Cordiali saluti. ABC

Relazione sul viaggio di maggio in Serbia e Bosnia

(15 – 27 maggio 2004)

Colpiti al cuore e… un po’ fuori di testa!

Colpiti al cuore e… un po’ fuori di testa! Cosa vuol dire?

Semplicemente che stiamo facendo una cosa fuori dell’ordinario, almeno

per “A, B, C, solidarietà e pace - ONLUS”: stiamo tentando di mantenere

il numero di giovani affidati a qualunque costo, anche chiedendone

altri senza prima avere sentito, come facciamo di solito, i vecchi

sostenitori se vorranno affidarne un altro o lasciare il progetto.

Proseguiranno? Speriamo di sì.

Oggi, tra Serbia e Bosnia, siamo a quasi 600 bambini (595 per

l’esattezza), due anni fa erano 700.

Oggi diciamo:

non vogliamo scendere sotto i 600 bambini affidati.

dobbiamo, quindi, recuperarne cinque e mantenere gli altri. Stiamo

tentando di fare questo perché c’è ancora bisogno di aiuto.

Non possiamo dimenticare alcune cose: quanto è accaduto a quella gente

è anche colpa nostra; due, sono nostri vicini e ci divide da loro un

braccio di mare; tre, ci amano, nonostante tutto; quattro, hanno

passato un sacco di guai e ancora ne passano.

Non sappiamo quello che sarà possibile fare nel futuro prossimo.

Dipende da voi, dalla vostra volontà di continuare a sostenere il

progetto di affido a distanza di giovani serbi e bosniaci; dalla nostra

capacità di comunicare come stanno veramente le cose.

Scusate, ora cominciamo a raccontarvi quello che abbiamo visto.

Domenica 16 - Siamo a Backa Topola, in Vojvodina. Seduti davanti al

televisore, in casa di amici, facciamo lezione di Politica. Vediamo

scorrere sul piccolo schermo le immagini di quelli che saranno i

protagonisti delle elezioni presidenziali del 13 giugno. Il favorito,

Tomislav Nikolic del Partito radicale serbo (per intenderci quello di

Seselj, in prigione all’Aja) accreditato, secondo uno degli ultimi

sondaggi, con il 29,9% dei voti, seguito da Boris Tadic (18,8%) del

Partito democratico (quello di Zoran Djindjic), arriva, buon ultimo, il

“Signor nessuno”, come lo hanno ribattezzato alcuni giornali serbi,

vale a dire Dragan Marsicanin, candidato di governo del Partito

democratico serbo (quello di Kostunica). Si attaccano tra loro e ognuno

parla male dell’altro. I problemi sono tanti, enormi! Riusciamo a

capire che l’attuale governo, di minoranza, è formato dal DSS (Partito

Democratico Serbo, conservatore), dal G17 (centrista liberale) e dal

SPO (Movimento per il Rinnovamento Serbo, monarchici conservatori), il

tutto con l’appoggio esterno del SPS (Partito socialista serbo, quello

di Milosevic). Nonostante il numero limitato dei seggi ottenuti (il

primo partito alle ultime politiche dello scorso dicembre è stato Il

Partito Radicale Serbo, ultranazionalista, che ha conquistato 82 dei

250 seggi del parlamento serbo, mentre il secondo, appunto quello di

Kostunica, ne ha presi 53 e quello del defunto Djindjic 37) Kostunica è

stato capace di assicurare al suo partito nove ministeri su 17 e

controlla, così, le cose importanti: economia, polizia, scuola ed

esercito. Anche a Backa Topola si usa fare lo “zapping” e così ci

ritroviamo sulla rete (una delle due che ha) di Bogoljub Karic,

candidato outsider alle presidenziali e uomo più ricco della Serbia,

proprio nel momento in cui nomina il partito che, comunque andranno le

presidenziali, intende fondare: “Napred Serbia”, vale a dire: “Forza

Serbia”. Sentiamo anche il nome del nostro primo ministro, Silvio

Berlusconi, quando, rispondendo alla domanda di un giornalista, Karic

dice: “abbiamo molto in comune”.

I politici hanno i macro-problemi da risolvere, la gente comune,

invece, deve confrontarsi con i maxi-problemi quotidiani. Quali?

Semplificando, pane e lavoro. Ce ne rendiamo conto quando cominciamo il

nostro giro nelle scuole e nelle fabbriche per consegnare le borse di

studio.

Lunedì 17 - La nostra prima tappa è Kriavaja, una scuola ad una decina

di chilometri da Backa Topola. Tutti, come sempre, gentili e cordiali.

Ci aspetta una sorpresa: tre fratellini, Nicola Gianluca (10 anni),

Stefano (9) e Cinzia (8), oriundi italiani. Mamma serba e padre

italiano (evidentemente molto prolifico, in tre anni tre figli). Mamma

ora in Serbia, sola e povera e senza alcun aiuto, papà italiano

“riparato” chissà dove. Situazione disperata, come tante altre. Non

possiamo fare finta di niente anche perché restiamo interdetti a

sentirli parlare italiano! Li aiutiamo in qualche maniera. Le cose non

sono quasi mai semplici e le emergenze si rincorrono, così, nella

scuola ungherese “Caki Lajos”, veniamo a sapere che c’è un bambino

pressoché denutrito. Ma perché non ci pensano loro? Ci pensano, ma i

casi sono tanti e se possono coinvolgere qualcun altro, tanto meglio.

E’ giusto! Interveniamo anche qui. Pensiamo: è un bambino

serbo-ungherese (ne abbiamo affidati anche altri) e, nel nostro

“piccolissimo”, vogliamo dare il nostro contributo al dialogo tra la

comunità ungherese e quella serba in una cittadina, Backa Topola, e in

una regione, la Backa (che insieme alla Srem e alla Banat forma la

Vojvodina), che si sta complicando la vita. Infatti, le forze

autonomiste sono aumentate, tanto che nello scorso aprile hanno

organizzato una “convention” con lo scopo di formare una coalizione

unitaria in vista delle prossime elezioni locali. Cosa chiedono? Alcuni

di andare, con tutta la terra, in Ungheria, altri si rivolgono alla

comunità internazionale perché difenda le ambizioni della provincia

autonoma a divenire “una moderna regione europea”, mentre i serbi, la

maggioranza assoluta, cominciano a temere la vichiana teoria dei corsi

e ricorsi storici, anche perché la ferita del Kosovo è ancora aperta.

Non vogliamo interferire in nulla, non è nel nostro modo di lavorare,

ma, alla prima occasione, vorremmo chiedere alla direttrice della “Caki

Lajos” (VEDERE CHI E’) perché va in Ungheria a comprare i libri

scolastici per i suoi alunni quando ce ne sono di serbi, naturalmente

in ungherese, ottimi. In questo contesto, sarebbe anche interessante

capire perché il governo ungherese eroga crediti agli ungheresi in

Vojvodina per consentirgli di comprare le aziende serbe che con la

privatizzazione sono in svendita. Chi ha ragione? Tutti e nessuno, come

il solito.

Anche con i bambini funziona così. Ci sono cose incomprensibili che

ormai accettiamo rassegnati: la mamma di una bambina di nome Jelena

rifiuta la nostra offerta di far controllare da un dermatologo la sua

piccola che ha la guancia sinistra rovinata da una dermatite o da un

angioma. Ci dice semplicemente e graziosamente: “No grazie!”. Perché?

Sembrerebbe appartenere ad una non meglio identificata setta (forse

quella del “Golgota”? Alcuni dicono sovvenzionata da servizi segreti

occidentali) che gli ha insegnato la rassegnazione, ad accettare quel

che arriva dal Cielo, in questo caso, probabilmente, le conseguenze

ambientali dell’inquinamento da bombardamenti o per colpa dell’acqua

inquinatissima del Canale grande di Backa, parte integrante

dell’idrosistema Danubio-Tisa-Danubio, che non si riesce a bonificare

per un conflitto di competenze, anche se il governo norvegese ha già

stanziato un milione e mezzo di Euro per l’opera di risanamento.

Martedì 18 – Andiamo a Nov Sad, alla scuola “Svetozar Markovic Toza”.

Novi Sad, seconda città serba e capoluogo della Vojvodina, presenta un

quadro politico opposto a quello nazionale: sono i Ds (quelli di

Diindjic, per intenderci) a governare, mentre chi gestisce il governo

centrale qui è all’opposizione. La Vojvodina, e in particolare Novi

Sad, è un po’ il bastian contrario dl Paese: il partito di maggioranza

relativa a livello nazionale, i Radicali, qui è stato emarginato con

successo, ed anche i Dss, che governano insieme con altri il Paese,

sono all’opposizione. Sarà forse perché tre dei sessanta ponti

bombardati sono a Novi Sad? L’”infarto” fluviale, come qualcuno chiama

il danno economico causato dallo sprofondamento di sei ponti sul

Danubio, ha complicato la vita un po’ a tutti: serbi, per ovvi motivi,

ungheresi, perché sono costretti a far fare a grano e mais assurdi

itinerari via terra, tedeschi e austriaci perché non arrivano più,

dall’Ucraina e dalla Romania cemento e materiale siderurgico.

Comunque: a dicembre, grazie soprattutto agli aiuti dei paesi

“danubiani” saranno ultimati i lavori al ponte della Libertà. Gli

altri ponti? Uno è finito e il terzo è in progetto. Ancora oggi, il

ponte provvisorio che unisce la collina all’università, ogni due

giorni, è aperto per consentire il passaggio delle chiatte con i loro

carichi.

Arriviamo davanti alla scuola. Abbiamo una foto fatta pochi giorni dopo

i bombardamenti (maggio ’99) dove si vedono i danni causati da una

bomba impazzita. Un’auto con le ruote verso il cielo ribaltata dallo

spostamento d’aria ricoperta di terra. Dietro, le finestre dissestate

della scuola. Cerchiamo lo stesso luogo e facciamo una foto, il prima e

il dopo, il passato, da non dimenticare, e il presente da cambiare.

Il direttore, Dragan, lentamente sta cominciando ad apprezzare la

nostra presenza. S'intrattiene a parlare con noi e ci accompagna a

visitare la scuola. Arranchiamo dietro di lui arrampicandoci sui due

piani dell’edificio: aula di fisica, di chimica, tecnica, inglese,

ungherese, lingua madre, ecc. E’ orgoglioso e frettoloso! Sempre meglio

del freddo distacco di due anni fa quando subentrò al signor Milorad

costretto a fare un bel salto indietro “degradato” a fare il maestro!

Ci accompagna persino all’esterno della scuola per mostrarci il luogo

dell’esplosione della bomba e racconta che ha aperto un cratere con un

diametro di 15 metri. Le aule di chimica e fisica ne portano, ancora

oggi, i segni. Distribuiamo le quote ed una bambina, alla domanda

cattiva “cosa farai con la borsa di studio?”, risponde: “ho promesso ad

una mia amica di pagargli il gelato”. Servono altre parole? Si parte

subito per Belgrado.

A Belgrado approdiamo dopo due ore. Belgrado è caotica, ed anche la

scuola non si sottrae a questa testimonianza di vita. La scuola è nel

sobborgo di Rakovica dove, il 17 aprile 1999, in una notte di “intenso

fuoco” fu bombardata una caserma che sorgeva in mezzo alle abitazioni,

a poche decine di metri dalla scuola “Nikola Tesla”. Per non fare

aspettare i genitori già raccolti in una grande aula andiamo subito a

consegnare le borse di studio. Riconosciamo quasi tutti. Qui, come

sempre, non riusciamo a sottrarci alle tradizionali mini-controversie:

alla fine della distribuzione delle borse di studio si presentano delle

mamme e dei papà di ragazzi ormai usciti dal progetto. Più o meno

consapevolmente, e comunque comprensibilmente, come diciamo a Roma, “ci

provano”. Spieghiamo loro che non abbiamo il denaro e non possiamo

consegnare loro alcuna quota. Lo sanno e, con cordialità, nonostante il

diniego, ci salutano e se ne vanno. Andiamo nell’ufficio del direttore.

C’è anche una vecchia amica di ABC, che ha avuto importanti

responsabilità nel dicastero della Sanità serba. Cominciamo a parlare

con il direttore e definiamo tutte le situazioni lasciate in sospeso a

novembre. Molte famiglie sono state costrette a cambiare casa ed è

stato impossibile rintracciarle, altre verranno la prossima volta. I

problemi non mancano. Ne parliamo tutti insieme. La vita è difficile, i

prezzi sono stabili (inevitabilmente), ma la vita delle famiglie è

sempre più difficile e, anche se l’infazione è sotto controllo e in tre

anni è scesa dal 40,7% del 2001 al 7,8% del 2003 (dati ufficiali della

Banca Nazionale Serba), chi si alza la mattina e deve mangiare non è

confortato da questo dato. Ci sono, infatti, sempre meno soldi e, da un

documento della Banca che ci siamo portati dietro, emerge un elemento

molto negativo: rispetto al 2002 la percentuale dei disoccupati è

aumentata dal 31,2% al 33,9% della forza lavoro (in realtà è di almeno

il 40% con punte pià alte in alcune aree del Paese). Troveremo

conferma di questi dati a Kragujevac dove arriviamo la sera.

Mercoledì 19 e giovedì 20 – Siamo a Kragujevac. Abbiamo l’intenzione di

cercare dati precisi sulla situazione sanitaria dei lavoratori, che

sono poi i papà e le mamme di tutti i ragazzi affidati. Non ne

troviamo. C’è “legittima reticenza” e chi promette documenti (analisi e

altro) ci delude. Pazienza! Abbiamo notizia, verbalmente, che i morti

ci sono e che le malattie sono in aumento. Spesso, nel giro di un mese,

si svelano patologie letali e piccoli manifesti mortuari tappezzano gli

alberi che conducono al cancello della Zastava. Riusciamo però, in ogni

caso, a trovare il testo trascritto e tradotto di un’intervista, andata

in onda sull’emittente serba B92 il 15 aprile scorso, fatta ad alcuni

operai che hanno partecipato al risanamento della Zastava. Dragan

Stojanovic, responsabile di una delle équipe che ha partecipato alla

bonifica della fabbrica, spiega che la rimozione delle macerie è stata

fatta senza alcuna precauzione e che in un mese ci sono stati sei

funerali. Paunovic, invece, è stato operato ed ha un polmone in meno.

Con i 4.500 dinari (circa 65 euro) del sussidio deve sopravvivere e

comprare le medicine. In tutto questo, asseriscono entrambi, l’aspetto

che dispiace di più è che l’azienda non riconosce l’esistenza di questi

problemi e si defila da qualsiasi sostegno agli operai che hanno avuto

patologie derivate dal lavoro all’interno della fabbrica. Dice Matic:

“se l’uranio si può bere come una limonata io mi scuserò”. Ma,

evidentemente, l’uranio delle bombe non è limonata anche perché, non a

caso, lo scorso novembre siamo stati testimoni diretti della presenza

di una delegazione dell’UNEP (United Nations Environmental Programme,

Programma Ambientale delle Nazioni Unite). La commissione dell’UNEP

cosa stava facendo a Kragujevac? Era in ferie? Probabilmente ha ragione

Knut Krusewitz, professore all’università di Berlino di Pianificazione

ambientale, che ha tentato, inascoltato, di spiegare al mondo quello

che era accaduto, contrapponendo la sua relazione a quella dell’UNEP.

Riportiamo soltanto le ultime righe del suo lavoro: “si tratta del

significativo danneggiamento delle risorse naturali ed economiche, in

un caso per lo sprigionamento di PCDDs (la diossina di Seveso) e di

PCDs e per l’altro per l’effetto di prodotti radiotossici e

chemiotossici derivati dalla disintegrazione delle munizioni all’uranio

impoverito. I cancerogeni saranno immagazzinati prevalentemente nei

prodotti agricoli e, al 95%, introdotti nella catena alimentare”. Siamo

propensi a dare ragione a lui e all’operaio Matic: l’uranio e la

diossina non sono limonata.

In due giorni a Kragujevac distribuiamo più di 250 borse di studio. I

ragazzi ci sono quasi tutti. La maggior parte dei non presenti sono

impegnati nei compiti in classe. Continuamo a fare foto. Alla fine del

viaggio saranno più di 1.200. I ragazzi assenti le consegneranno al

sindacato che le spedirà in Italia. Durante la distribuzione delle

quote vediamo le stesse persone. C’è “il ministro” (il suo soprannome

deriva dal fatto che ha preso a schiaffi il vecchio ministro del

Lavoro), il marito della signora Al Mamuri tornato dall’Iraq in Serbia

per eludere il destino beffardo, dopo un periodo di “riposo” con le tre

mogli irachene e per sfuggire alla situazione locale. La sera partiamo

per Nis.

Venerdì 21 – Tomasevic Bojana, alla Min Fitip, una delle affidate,

arriva accompagnata dal nonno. Sì, lo riconoscono, è proprio lui, l’ex

direttore generale della fabbrica. Un signore simpatico e dimesso che

sorride senza alcun compiacimento e che firma la ricevuta della borsa

di studio per sua nipote come uno dei tanti operai che sono stati suoi

dipendenti. Arrivano tutti, pian piano. Ci salutano. Vorremmo scattare

qualche foto all’interno della fabbrica. Ci spiegano che non è

possibile. Lo sapevamo, ma abbiamo tentato. Probabilmente anche la

Min-Fitip è nell’elenco delle aziende, grandi e piccole, in vendita.

Nel luglio 2001 è stata creata, appositamente, un’Agenzia per le

Privatizzazioni e, secondo i dati ufficiali che ha pubblicato, nel

2002, su 366 aziende in privatizzazione, 274 sono state vendute con un

introito di 350 milioni di dollari (fonte: Banca Nazionale Serba). A

quanto saranno vendute la Min-Fitip e l’Elktronska Industria? Ogni

volta che una fabbrica o un’azienda sono alienate aumentano il numero

dei disoccupati, la povertà, le malattie, la disperazione, la sfiducia

nelle istituzioni, la rabbia, e chi più ne ha più ne metta. Si è poveri

e lo si diventa sempre di più.

A Nis siamo ospiti di amici a Niska Banja dove, nel pomeriggio, andiamo

a distribuire le “skolska stipendia” nella scuola “Ivan Goran Kovacic”.

Nell’atrio ci attendono i ragazzi. Non appena entriamo

cominciano a cantare. Sono tornati da poco da una “gara canora” tra

tutte le scuole della Serbia e sono arrivati secondi. Sono bravi!

Subito dopo cominciamo a consegnare le borse di studio. I problemi

anche qui non mancano: cerchiamo di capire come affrontare tre

emergenze. Un bambino leucemico, un secondo con problemi di crescita e

la terza operata al cuore e con una deformazione del palato.

Tenteremo di trovare tra i tanti amici dell’associazione una

possibilità di cura per il piccolo leucemico, un farmaco, il

Genotropin, per il secondo, e faremo controllare in Serbia la terza dal

medico che l’ha in cura e che, coincidenza positiva, è il figliolo di

una nostra cara amica serba. Ci capita di chiedere a molti affidati se

hanno corrispondenza con i loro amici italiani, alcuni dicono di sì,

altri no, altri ancora ci dicono di avere scritto ma di non avere avuto

risposta. Spieghiamo a tutti che come per loro non c’è alcun obbligo a

corrispondere con i loro sostenitori, così non c’è per chi li aiuta.

Comunque, la “skolska stipendia” è già un segno d’amicizia importante e

tangibile.

Sabato 22, riposo. Con alcuni amici parliamo del Kosovo partendo da una

domanda: cosa ne pensate della possibilità, prefigurata da Kostunica,

di una cantonalizzazione (un’ amministrazione serba e albanese

all’interno della provincia sul modello della divisione interna della

Bosnia ed Erzegovina) partendo dal presupposto che un “paradiso

multietnico” non è realizzabile? Quasi tutti sono convinti che è

impossibile convivere con gli albanesi, la maggior parte vede nella

cantonalizzazione l’unica strada, pochi pensano che si debbano mandare

(dimenticando gli accordi internazionali che lo impediscono) esercito e

polizia serbi. Molti parlano bene dei militari italiani che hanno

difeso i serbi e i loro monasteri, dove possibile. Tutti dimentichiamo

due cose: 1) la Ue continua a sostenere un’unica soluzione: una regione

multietnica; 2) contro la cantonalizzazione si è schierato il leader

albanese Rugova il quale ha detto che è una cosa impossibile. Rugova,

d’altra parte, ormai si comporta da verso e conciliante padrone di

casa: ha promesso ai serbi che farà ricostruire le loro case e le loro

chiese distrutte dai suoi amici lo scorso marzo.

Domenica 23. La famiglia Zuza parte per l’America. Profughi dalla

Bosnia, per la precisione da Konjic, tra Mostar e Sarajevo, da più

dieci anni vivono, madre, padre e due figli, un maschio, Miroslav, 15

anni, e una femmina (affidata), Jovana, 16 anni, nell’hotel “Serbja” di

Niska Banja. Il Commissariato per i rifugiati delle Nazioni Unite gli

ha dato questa possibilità. Partono per Las Vegas. Andiamo a salutarli,

insieme ad altri amici. Manca un’ora alla partenza. Piangono e noi con

loro. Ci tratteniamo il tempo per augurargli ogni bene. Lo meritano.

Hanno il coraggio della disperazione indispensabile per un passo del

genere. Vorremmo poter comunicare meglio di quanto non sappiamo fare

quello che percepiamo in loro: paura dell’ignoto e speranza in un

futuro migliore. Alle 8 prendono i loro bagagli. Arriva l’autobus per

Belgrado. La disperazione dei genitori, vecchi, che sanno di non poter

più vedere i loro figli; il pianto degli amici, giovani, che presto

dimenticheranno. Non rischiamo il patetico! Andiamo avanti!

Sono i ragazzi e i genitori della piccola scuola di Donja Vrezina, dove

andiamo dopo la partenza della famiglia Zuza, a farci dimenticare la

tristezza di queste prime ore di domenica. Mentre distribuiamo le quote

arriva, a piedi, un vecchio giornalista che vuole sapere qualcosa sul

nostro lavoro. E’ stato a Roma per diversi anni ed ora è rientrato in

Serbia e per arrotondare una pensione inesistente si è messo a fare il

“free-lance”. Fa foto e si informa. Il Comitato dei genitori della

scuolina ha preparato un gran rinfresco. Ci dicono che i serbi sono

fatti così: sono disposti a non mangiare pur di accogliere bene degli

amici. I bambini sono tutti lì ed anche i genitori che si prendono in

giro. Il “soggetto” è soprattutto il marito di una bella signora che

torna ogni due mesi dalla Slovenia dove è andato è riuscito a trovare

lavoro.

Facili allusioni, ma meno facile ironia quella del destino di Predrag:

trovare lavoro proprio dove avvennero i primi scontri, nel giugno del

1991, tra la Difesa territoriale slovena e l’armata jugoslava. Ma sono

passati 13 anni… e quasi tutti bambini che oggi hanno preso la “skolska

stipendjia” , per fortuna, a quel tempo non erano neanche nati. E

questa è la grande speranza, dimenticare e ricominciare!

Lunedì 24 – Fa un freddo cane! All’orizzonte vediamo le montagne

bulgare. Entriamo nell’Elektronska Indusrtrija, ex colosso locale e

nazionale che produceva elettrodomestici. All’E.I. le cose vanno ancor

peggio che alla Min- Fitip. Dei circa 20.000 dipendenti sono 800 quelli

che lavorano e 2.400 quelli a disposizione che sperano di essere

chiamati. Gli altri sono disoccupati. Le retribuzioni vanno dai 4.000

ai 18.000 dinari , vale a dire da 60 a 250 euro (a prendere 18.000

dinari sono soltanto 15 tecnici superspecializzati). Andiamo dai

bambini e dai genitori riuniti, come il solito, nella vastissima mensa.

Stiamo al buio: non si accende la luce e non c’è acqua. Ci si è

abituati a risparmiare in qualsiasi circostanza e per tutto. Cominciamo

a chiamare e, come abbiamo fatto, in tutte le scuole e le fabbriche,

spieghiamo che scatteremo due foto da spedire ai loro amici italiani.

Sono lì “docili” e pazienti. Cominciamo la consegna delle “skolska

stipendia” e, com’è avvenuto in tutti i posti dove siamo stati, anche

qui sul volto di questa gente rassegnazione. Parlando con loro sentiamo

che sono scoraggiati. Hanno poche speranze nel futuro e credono poco

nella classe politica che li governa. Sono sempre gli stessi (non

possiamo dargli torto), anche i partiti sono sempre gli stessi (anche

questo è vero), se capita la disgrazia di ammalarsi ci si può anche

rassegnare a morire (verissimo, tanto che tutt’intorno è tappezzato di

piccoli manifesti con l’annuncio della morte di qualcuno, spesso

prematuramente), il lavoro non c’è e i giovani non hanno un futuro. C’è

anche chi ha un sussulto e si arrabbia mentre parla, ma la maggior

parte sono quieti.

Da un caro amico, riusciamo ad avere, per la prima volta durante il

nostro viaggio, un documento ufficiale sottoscritto dal direttore

dell’Ufficio di collocamento. Proviamo a capirci qualcosa. Scopriamo

che i disoccupati a Nis, al 5 aprile scorso, sono 46.036 dei quali

24.488 donne. I posti disponibili, all’Ufficio di collocamento, sono

invece 5.540 (2.363 a tempo indeterminato e 3.177 a termine). Proviamo

a capire di quale tipo di lavori si tratta, ma non ci riusciamo.

Facendo i conti a “maniera nostra” la percentuale ufficiale dei

disoccupati a Nis, anche se non possiamo essere precisi perché non

conosciamo il totale della forza lavoro locale, dovrebbe essere di

circa il 40% (la Banca Nazionale Serba parla, per il 2003, di 33,7%).

Con i sindacalisti cerchiamo di capire poi la situazione politica. E’

praticamente dall’inizio del viaggio che andiamo in giro con un pezzo

di carta, dove abbiamo disegnato un semicerchio (il Parlamento serbo) e

scritto, cercando di collocarli nella loro posizione “fisiologica” , i

nomi dei partiti. Da questo schema esatto e semplice, ne viene fuori

un’immagine sbilanciata completamente a destra del Parlamento, anche se

il Partito democratico (ex Djindjic) lo scorso ottobre è entrato

nell’Internazionale socialista. A sinistra sembrerebbe essere presente

soltanto il Partito socialista serbo (ex Milosevic), messo storicamente

fuori gioco dagli eventi. Tutti, dopo aver osservato lo schema,

concordano che è una situazione sbagliata. Alcuni affermano che ci sono

dei piccoli partiti a sinistra, altri che hanno tentato di riempire

questo vuoto con un nuovo partito il “Labour”, ma per ora l’esperienza

è fallita, altri ancora che un partito di sinistra c’è, quello di

Milosevic. Tutti concordano su una cosa: non c’è nessuna figura

politica, a sinistra, capace di raccogliere consensi e democratizzare

così un parlamento sbilanciato e litigioso.

Martedì 25 – Partenza per la Bosnia. Nel primo pomeriggio siamo a

Rogatica alla scuola “Sveti Sava”. Sono 1.200 i bambini che la

frequentano distribuiti su tre turni (si comincia alle 7,20 e si

finisce alle 18 circa). Quest’anno hanno cominciato la scuola anche

bambini di sei anni. Qui, contrariamente a quanto avviene in Serbia (la

legge non ha trovato attuazione in seguito al cambiamento del governo),

la riforma della scuola è stata applicata. Siamo un po’ confusi!

Entriamo con bambini e genitori in un’aula per distribuire le quote di

affido. Una mamma sale al primo piano della scuola arracampicandosi con

l’aiuto di una stampella. Non sta bene, ma vuole salutarci egualmente.

Comincia la distribuzione delle “borse di studio”. Un Papà è solo: il

piccolo Mihali è all’ospedale. Pochi mesi fa è morta la moglie e ora il

bambino, paraplegico, sta accusando il colpo. Storie di disperazione.

Vorremmo evitare di raccontarle, ma sono testimonianze importanti. Ci

sono però anche i momenti lieti: l’accoglienza di genitori e ragazzi,

le letterine per gli affidatari, i piccoli regali fatti con il cuore e

il sacrifico, le foto fatte insieme.

Chiacchieriamo un po’ con il vice preside della scuola. Sarà il tempo

che passa, ma ci rendiamo conto che c’è una maggiore disponibilità, in

tutti, a parlare di più, ad affrontare argomenti da anni elusi (con

l’eccezione di Lukavica, dove il direttore, continua a dirci, in

italiano, “Milan, grande squadra”). Durante il colloquio annotiamo

delle cose significative dette dal nostro amico: “passo la frontiera

con la Serbia decine di volte al mese e ogni volta devo mostrare il

passaporto. Io sono serbo, come i serbi di Serbia! E’ umilitante!”.

“Davanti c’è una persona, ma dietro ce n’è sempre un’altra”. “In ogni

casa della Republika Srpska, anche la più sperduta, l’ospite è sacro e

ci sarà sempre per lui un pasto!”. Stereotipi? No.

Risaliamo in macchina e via verso Pale, ex roccaforte di Radovan

Karadzic, capo dei serbi di Bosnia e ricercato numero uno per crimini

di guerra. Pale, ex capitale della Republika scalzata dalla più

moderata Banja Luka. La casa dove siamo ospitati è vicinissima alla

chiesa e alla canonica dove il primo aprile scorso, un commando della

Sfor (veniamo a sapere casualmente da “alcuni italiani” che si sarebbe

trattato di militari americani che “non vanno per il sottile”) ha fatto

saltare la porta con una carica di esplosivo ferendo gravemente il

parroco e il figlio. “L’esplosione ha frantumato i vetri delle

abitazioni circostanti (ad una sessantina di metri perché chiesa e

canonica sono al centro di una piazza-giardino) e non ci si poteva

affacciare perché i militari che circondavano gli edifici puntavano i

fucili”, ci dicono. Ma lasciamo stare queste cose!

Mercoledì 26 – La scuola “Pale” di Pale nel 2005 compirà cent’anni! Non

pochi! I bambini affidati sono una trentina e quasi tutti per arrivare

a scuola devono percorrere, ogni giorno, diversi chilometri a piedi. Ad

attenderci c’è anche Donato, un socio di San Donato Milanese, che è

venuto a trovare il suo “figlioccio”, Bosko, ed è ospite della famiglia

del bambino. E’ entusiasta di questa esperienza e ci parla di come è

stato accolto e della situazione difficile della famiglia. Per lui è

stata organizzata una gran festa alla quale hanno partecipato tutti i

vicini.

Ognuno ha portato qualcosa e, in poco tempo, è stato allestito un vero

e proprio banchetto! Cominciamo a distribuire le borse di studio e

facciamo le foto. Al direttore chiediamo, come abbiamo fatto in tutte

le altre città, schede di nuovi ragazzi da affidare. Finiamo presto.

Vorremmo andare a fare una camminata nei boschi. Ce lo sconsigliano.

Ancora troppi posti contaminati da mine e ordigni inesplosi. Notizia

ufficiale: in Bosnia sono 1.366 i centri abitati contaminati e, secondo

il Centro per lo sminamento, sono registrati oltre 10.000 campi minati.

Meglio evitare per non correre il rischio di aumentare il numero delle

vittime, 1.048, registrate dalla fine della guerra (1995).

Nel pomeriggio andiamo a Lukavica, enclave serba alla periferia di

Sarajevo. Il direttore della scuola “Sveti Sava”, milanista

“sfegatato”, è alle prese con il Consiglio d’istituto e ci accoglie il

suo vice. Entriamo nell’aula dove ci aspettano i bambini con i

genitori. Tra loro Blazic Sasa, “recordboy”: undici tra fratelli e

sorelle. A vedere il papà, un poco malridotto, zoppica e si sostiene

con una stampella, non ci sembra possibile che sia così “prolifico”. Ci

asteniamo da commenti, anche se alcuni suggerimenti gli servirebbero.

Distribuiamo le quote e riceviamo tre baci da ciascun affidato. Arriva

anche il direttore e, dopo i saluti, ci chiede subito se vogliamo

aiutarlo a costruire una palestra. Infatti, la scuola di Pale è un dono

della cooperazione giapponese e loro costruiscono le scuole senza

palestre. Gli diciamo che siamo una piccola associazione che non può

permettersi una spesa del genere. Di fronte al diniego ci svela che ha,

comunque, un probabile donatore. E’ una vecchia volpe mr. Milovan. Uomo

eccezionale, capace di fare il bene dei suoi alunni senza esporre se

stesso e chicchessia. Cauto al punto di rispondere “tutto OK” alla

banale domanda: “come vanno le cose a Lukavica?”. Ma basta dare

un’occhiata ai bambini e ai genitori per capire che le cose non sono

per niente OK a Lukavica che, come tutta la Republika Srpska, ha

problemi enormi: 43% di disoccupazione, miseria e fame, sporcizia e

disperazione. Giovedì ripartiamo per l’Italia!

> Da: "Abconlus" <info @ abconlus.it>

> Data: Lun 7 Giu 2004 06:38:32 Europe/Rome

> A: ABC - A, B, C, Solidarietà e pace <abcsolidarieta @ tiscalinet.it>

> Oggetto: da ABC - Relazione viaggio in Serbia e Repubblika Sprspa

> maggio 2004

> Rispondere-A: <info @ abconlus.it>

>

> Gentili amici,

> in allegato la relazione del recente viaggio nelle Repubbliche di

> Srbja i Cerna Gora e Srpska.

> Cordiali saluti. ABC

Relazione sul viaggio di maggio in Serbia e Bosnia

(15 – 27 maggio 2004)

Colpiti al cuore e… un po’ fuori di testa!

Colpiti al cuore e… un po’ fuori di testa! Cosa vuol dire?

Semplicemente che stiamo facendo una cosa fuori dell’ordinario, almeno

per “A, B, C, solidarietà e pace - ONLUS”: stiamo tentando di mantenere

il numero di giovani affidati a qualunque costo, anche chiedendone

altri senza prima avere sentito, come facciamo di solito, i vecchi

sostenitori se vorranno affidarne un altro o lasciare il progetto.

Proseguiranno? Speriamo di sì.

Oggi, tra Serbia e Bosnia, siamo a quasi 600 bambini (595 per

l’esattezza), due anni fa erano 700.

Oggi diciamo:

non vogliamo scendere sotto i 600 bambini affidati.

dobbiamo, quindi, recuperarne cinque e mantenere gli altri. Stiamo

tentando di fare questo perché c’è ancora bisogno di aiuto.

Non possiamo dimenticare alcune cose: quanto è accaduto a quella gente

è anche colpa nostra; due, sono nostri vicini e ci divide da loro un

braccio di mare; tre, ci amano, nonostante tutto; quattro, hanno

passato un sacco di guai e ancora ne passano.

Non sappiamo quello che sarà possibile fare nel futuro prossimo.

Dipende da voi, dalla vostra volontà di continuare a sostenere il

progetto di affido a distanza di giovani serbi e bosniaci; dalla nostra

capacità di comunicare come stanno veramente le cose.

Scusate, ora cominciamo a raccontarvi quello che abbiamo visto.

Domenica 16 - Siamo a Backa Topola, in Vojvodina. Seduti davanti al

televisore, in casa di amici, facciamo lezione di Politica. Vediamo

scorrere sul piccolo schermo le immagini di quelli che saranno i

protagonisti delle elezioni presidenziali del 13 giugno. Il favorito,

Tomislav Nikolic del Partito radicale serbo (per intenderci quello di

Seselj, in prigione all’Aja) accreditato, secondo uno degli ultimi

sondaggi, con il 29,9% dei voti, seguito da Boris Tadic (18,8%) del

Partito democratico (quello di Zoran Djindjic), arriva, buon ultimo, il

“Signor nessuno”, come lo hanno ribattezzato alcuni giornali serbi,

vale a dire Dragan Marsicanin, candidato di governo del Partito

democratico serbo (quello di Kostunica). Si attaccano tra loro e ognuno

parla male dell’altro. I problemi sono tanti, enormi! Riusciamo a

capire che l’attuale governo, di minoranza, è formato dal DSS (Partito

Democratico Serbo, conservatore), dal G17 (centrista liberale) e dal

SPO (Movimento per il Rinnovamento Serbo, monarchici conservatori), il

tutto con l’appoggio esterno del SPS (Partito socialista serbo, quello

di Milosevic). Nonostante il numero limitato dei seggi ottenuti (il

primo partito alle ultime politiche dello scorso dicembre è stato Il

Partito Radicale Serbo, ultranazionalista, che ha conquistato 82 dei

250 seggi del parlamento serbo, mentre il secondo, appunto quello di

Kostunica, ne ha presi 53 e quello del defunto Djindjic 37) Kostunica è

stato capace di assicurare al suo partito nove ministeri su 17 e

controlla, così, le cose importanti: economia, polizia, scuola ed

esercito. Anche a Backa Topola si usa fare lo “zapping” e così ci

ritroviamo sulla rete (una delle due che ha) di Bogoljub Karic,

candidato outsider alle presidenziali e uomo più ricco della Serbia,

proprio nel momento in cui nomina il partito che, comunque andranno le

presidenziali, intende fondare: “Napred Serbia”, vale a dire: “Forza

Serbia”. Sentiamo anche il nome del nostro primo ministro, Silvio

Berlusconi, quando, rispondendo alla domanda di un giornalista, Karic

dice: “abbiamo molto in comune”.

I politici hanno i macro-problemi da risolvere, la gente comune,

invece, deve confrontarsi con i maxi-problemi quotidiani. Quali?

Semplificando, pane e lavoro. Ce ne rendiamo conto quando cominciamo il

nostro giro nelle scuole e nelle fabbriche per consegnare le borse di

studio.

Lunedì 17 - La nostra prima tappa è Kriavaja, una scuola ad una decina

di chilometri da Backa Topola. Tutti, come sempre, gentili e cordiali.

Ci aspetta una sorpresa: tre fratellini, Nicola Gianluca (10 anni),

Stefano (9) e Cinzia (8), oriundi italiani. Mamma serba e padre

italiano (evidentemente molto prolifico, in tre anni tre figli). Mamma

ora in Serbia, sola e povera e senza alcun aiuto, papà italiano

“riparato” chissà dove. Situazione disperata, come tante altre. Non

possiamo fare finta di niente anche perché restiamo interdetti a

sentirli parlare italiano! Li aiutiamo in qualche maniera. Le cose non

sono quasi mai semplici e le emergenze si rincorrono, così, nella

scuola ungherese “Caki Lajos”, veniamo a sapere che c’è un bambino

pressoché denutrito. Ma perché non ci pensano loro? Ci pensano, ma i

casi sono tanti e se possono coinvolgere qualcun altro, tanto meglio.

E’ giusto! Interveniamo anche qui. Pensiamo: è un bambino

serbo-ungherese (ne abbiamo affidati anche altri) e, nel nostro

“piccolissimo”, vogliamo dare il nostro contributo al dialogo tra la

comunità ungherese e quella serba in una cittadina, Backa Topola, e in

una regione, la Backa (che insieme alla Srem e alla Banat forma la

Vojvodina), che si sta complicando la vita. Infatti, le forze

autonomiste sono aumentate, tanto che nello scorso aprile hanno

organizzato una “convention” con lo scopo di formare una coalizione

unitaria in vista delle prossime elezioni locali. Cosa chiedono? Alcuni

di andare, con tutta la terra, in Ungheria, altri si rivolgono alla

comunità internazionale perché difenda le ambizioni della provincia

autonoma a divenire “una moderna regione europea”, mentre i serbi, la

maggioranza assoluta, cominciano a temere la vichiana teoria dei corsi

e ricorsi storici, anche perché la ferita del Kosovo è ancora aperta.

Non vogliamo interferire in nulla, non è nel nostro modo di lavorare,

ma, alla prima occasione, vorremmo chiedere alla direttrice della “Caki

Lajos” (VEDERE CHI E’) perché va in Ungheria a comprare i libri

scolastici per i suoi alunni quando ce ne sono di serbi, naturalmente

in ungherese, ottimi. In questo contesto, sarebbe anche interessante

capire perché il governo ungherese eroga crediti agli ungheresi in

Vojvodina per consentirgli di comprare le aziende serbe che con la

privatizzazione sono in svendita. Chi ha ragione? Tutti e nessuno, come

il solito.

Anche con i bambini funziona così. Ci sono cose incomprensibili che

ormai accettiamo rassegnati: la mamma di una bambina di nome Jelena

rifiuta la nostra offerta di far controllare da un dermatologo la sua

piccola che ha la guancia sinistra rovinata da una dermatite o da un

angioma. Ci dice semplicemente e graziosamente: “No grazie!”. Perché?

Sembrerebbe appartenere ad una non meglio identificata setta (forse

quella del “Golgota”? Alcuni dicono sovvenzionata da servizi segreti

occidentali) che gli ha insegnato la rassegnazione, ad accettare quel

che arriva dal Cielo, in questo caso, probabilmente, le conseguenze

ambientali dell’inquinamento da bombardamenti o per colpa dell’acqua

inquinatissima del Canale grande di Backa, parte integrante

dell’idrosistema Danubio-Tisa-Danubio, che non si riesce a bonificare

per un conflitto di competenze, anche se il governo norvegese ha già

stanziato un milione e mezzo di Euro per l’opera di risanamento.

Martedì 18 – Andiamo a Nov Sad, alla scuola “Svetozar Markovic Toza”.

Novi Sad, seconda città serba e capoluogo della Vojvodina, presenta un

quadro politico opposto a quello nazionale: sono i Ds (quelli di

Diindjic, per intenderci) a governare, mentre chi gestisce il governo

centrale qui è all’opposizione. La Vojvodina, e in particolare Novi

Sad, è un po’ il bastian contrario dl Paese: il partito di maggioranza

relativa a livello nazionale, i Radicali, qui è stato emarginato con

successo, ed anche i Dss, che governano insieme con altri il Paese,

sono all’opposizione. Sarà forse perché tre dei sessanta ponti

bombardati sono a Novi Sad? L’”infarto” fluviale, come qualcuno chiama

il danno economico causato dallo sprofondamento di sei ponti sul

Danubio, ha complicato la vita un po’ a tutti: serbi, per ovvi motivi,

ungheresi, perché sono costretti a far fare a grano e mais assurdi

itinerari via terra, tedeschi e austriaci perché non arrivano più,

dall’Ucraina e dalla Romania cemento e materiale siderurgico.

Comunque: a dicembre, grazie soprattutto agli aiuti dei paesi

“danubiani” saranno ultimati i lavori al ponte della Libertà. Gli

altri ponti? Uno è finito e il terzo è in progetto. Ancora oggi, il

ponte provvisorio che unisce la collina all’università, ogni due

giorni, è aperto per consentire il passaggio delle chiatte con i loro

carichi.

Arriviamo davanti alla scuola. Abbiamo una foto fatta pochi giorni dopo

i bombardamenti (maggio ’99) dove si vedono i danni causati da una

bomba impazzita. Un’auto con le ruote verso il cielo ribaltata dallo

spostamento d’aria ricoperta di terra. Dietro, le finestre dissestate

della scuola. Cerchiamo lo stesso luogo e facciamo una foto, il prima e

il dopo, il passato, da non dimenticare, e il presente da cambiare.

Il direttore, Dragan, lentamente sta cominciando ad apprezzare la

nostra presenza. S'intrattiene a parlare con noi e ci accompagna a

visitare la scuola. Arranchiamo dietro di lui arrampicandoci sui due

piani dell’edificio: aula di fisica, di chimica, tecnica, inglese,

ungherese, lingua madre, ecc. E’ orgoglioso e frettoloso! Sempre meglio

del freddo distacco di due anni fa quando subentrò al signor Milorad

costretto a fare un bel salto indietro “degradato” a fare il maestro!

Ci accompagna persino all’esterno della scuola per mostrarci il luogo

dell’esplosione della bomba e racconta che ha aperto un cratere con un

diametro di 15 metri. Le aule di chimica e fisica ne portano, ancora

oggi, i segni. Distribuiamo le quote ed una bambina, alla domanda

cattiva “cosa farai con la borsa di studio?”, risponde: “ho promesso ad

una mia amica di pagargli il gelato”. Servono altre parole? Si parte

subito per Belgrado.

A Belgrado approdiamo dopo due ore. Belgrado è caotica, ed anche la

scuola non si sottrae a questa testimonianza di vita. La scuola è nel

sobborgo di Rakovica dove, il 17 aprile 1999, in una notte di “intenso

fuoco” fu bombardata una caserma che sorgeva in mezzo alle abitazioni,

a poche decine di metri dalla scuola “Nikola Tesla”. Per non fare

aspettare i genitori già raccolti in una grande aula andiamo subito a

consegnare le borse di studio. Riconosciamo quasi tutti. Qui, come

sempre, non riusciamo a sottrarci alle tradizionali mini-controversie:

alla fine della distribuzione delle borse di studio si presentano delle

mamme e dei papà di ragazzi ormai usciti dal progetto. Più o meno

consapevolmente, e comunque comprensibilmente, come diciamo a Roma, “ci

provano”. Spieghiamo loro che non abbiamo il denaro e non possiamo

consegnare loro alcuna quota. Lo sanno e, con cordialità, nonostante il

diniego, ci salutano e se ne vanno. Andiamo nell’ufficio del direttore.

C’è anche una vecchia amica di ABC, che ha avuto importanti

responsabilità nel dicastero della Sanità serba. Cominciamo a parlare

con il direttore e definiamo tutte le situazioni lasciate in sospeso a

novembre. Molte famiglie sono state costrette a cambiare casa ed è

stato impossibile rintracciarle, altre verranno la prossima volta. I

problemi non mancano. Ne parliamo tutti insieme. La vita è difficile, i

prezzi sono stabili (inevitabilmente), ma la vita delle famiglie è

sempre più difficile e, anche se l’infazione è sotto controllo e in tre

anni è scesa dal 40,7% del 2001 al 7,8% del 2003 (dati ufficiali della

Banca Nazionale Serba), chi si alza la mattina e deve mangiare non è

confortato da questo dato. Ci sono, infatti, sempre meno soldi e, da un

documento della Banca che ci siamo portati dietro, emerge un elemento

molto negativo: rispetto al 2002 la percentuale dei disoccupati è

aumentata dal 31,2% al 33,9% della forza lavoro (in realtà è di almeno

il 40% con punte pià alte in alcune aree del Paese). Troveremo

conferma di questi dati a Kragujevac dove arriviamo la sera.

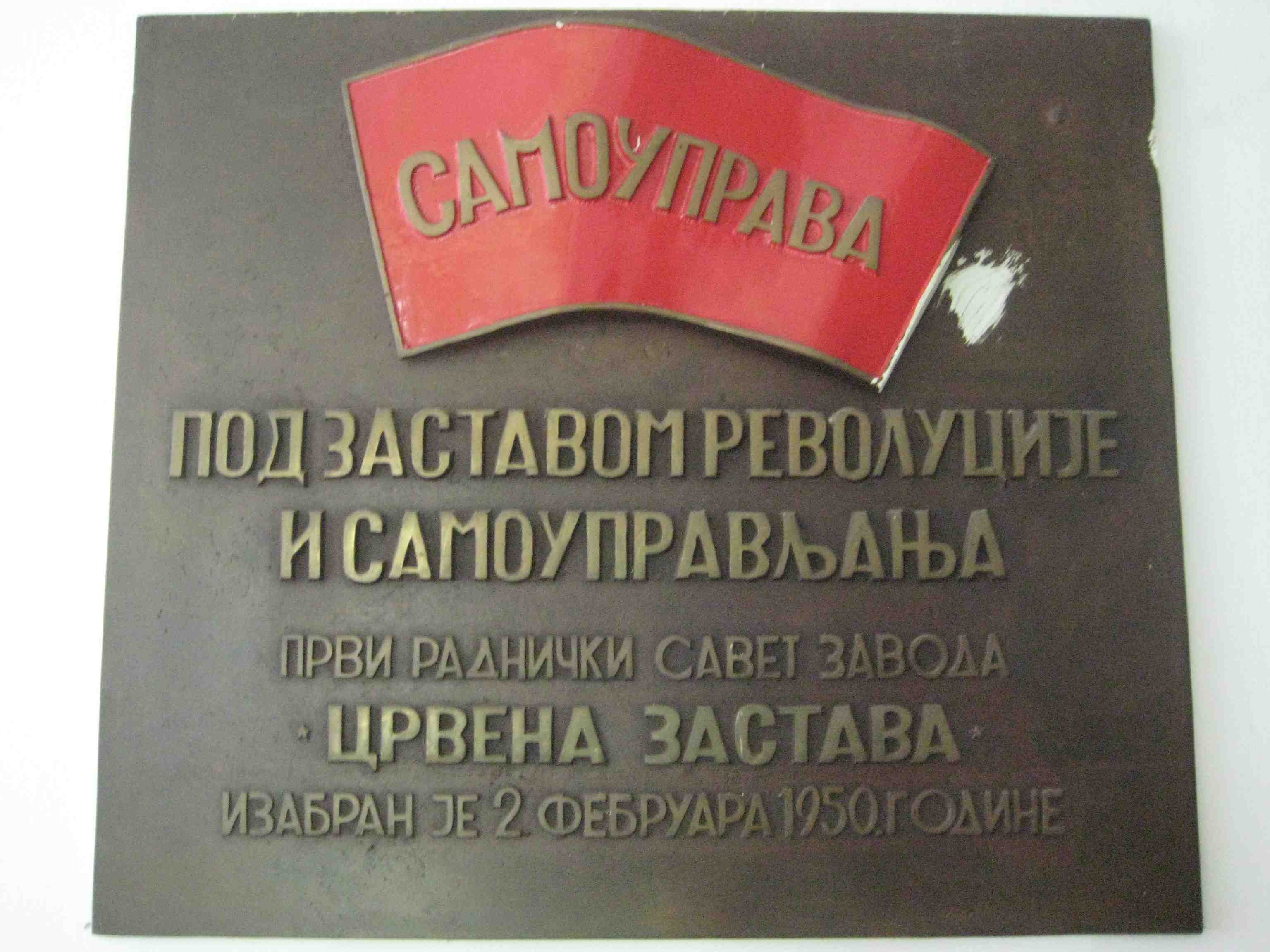

Mercoledì 19 e giovedì 20 – Siamo a Kragujevac. Abbiamo l’intenzione di

cercare dati precisi sulla situazione sanitaria dei lavoratori, che

sono poi i papà e le mamme di tutti i ragazzi affidati. Non ne

troviamo. C’è “legittima reticenza” e chi promette documenti (analisi e

altro) ci delude. Pazienza! Abbiamo notizia, verbalmente, che i morti

ci sono e che le malattie sono in aumento. Spesso, nel giro di un mese,

si svelano patologie letali e piccoli manifesti mortuari tappezzano gli

alberi che conducono al cancello della Zastava. Riusciamo però, in ogni

caso, a trovare il testo trascritto e tradotto di un’intervista, andata

in onda sull’emittente serba B92 il 15 aprile scorso, fatta ad alcuni

operai che hanno partecipato al risanamento della Zastava. Dragan

Stojanovic, responsabile di una delle équipe che ha partecipato alla

bonifica della fabbrica, spiega che la rimozione delle macerie è stata

fatta senza alcuna precauzione e che in un mese ci sono stati sei

funerali. Paunovic, invece, è stato operato ed ha un polmone in meno.

Con i 4.500 dinari (circa 65 euro) del sussidio deve sopravvivere e

comprare le medicine. In tutto questo, asseriscono entrambi, l’aspetto

che dispiace di più è che l’azienda non riconosce l’esistenza di questi

problemi e si defila da qualsiasi sostegno agli operai che hanno avuto

patologie derivate dal lavoro all’interno della fabbrica. Dice Matic:

“se l’uranio si può bere come una limonata io mi scuserò”. Ma,

evidentemente, l’uranio delle bombe non è limonata anche perché, non a

caso, lo scorso novembre siamo stati testimoni diretti della presenza

di una delegazione dell’UNEP (United Nations Environmental Programme,

Programma Ambientale delle Nazioni Unite). La commissione dell’UNEP

cosa stava facendo a Kragujevac? Era in ferie? Probabilmente ha ragione

Knut Krusewitz, professore all’università di Berlino di Pianificazione

ambientale, che ha tentato, inascoltato, di spiegare al mondo quello

che era accaduto, contrapponendo la sua relazione a quella dell’UNEP.

Riportiamo soltanto le ultime righe del suo lavoro: “si tratta del

significativo danneggiamento delle risorse naturali ed economiche, in

un caso per lo sprigionamento di PCDDs (la diossina di Seveso) e di

PCDs e per l’altro per l’effetto di prodotti radiotossici e

chemiotossici derivati dalla disintegrazione delle munizioni all’uranio

impoverito. I cancerogeni saranno immagazzinati prevalentemente nei

prodotti agricoli e, al 95%, introdotti nella catena alimentare”. Siamo

propensi a dare ragione a lui e all’operaio Matic: l’uranio e la

diossina non sono limonata.

In due giorni a Kragujevac distribuiamo più di 250 borse di studio. I

ragazzi ci sono quasi tutti. La maggior parte dei non presenti sono

impegnati nei compiti in classe. Continuamo a fare foto. Alla fine del

viaggio saranno più di 1.200. I ragazzi assenti le consegneranno al

sindacato che le spedirà in Italia. Durante la distribuzione delle

quote vediamo le stesse persone. C’è “il ministro” (il suo soprannome

deriva dal fatto che ha preso a schiaffi il vecchio ministro del

Lavoro), il marito della signora Al Mamuri tornato dall’Iraq in Serbia

per eludere il destino beffardo, dopo un periodo di “riposo” con le tre

mogli irachene e per sfuggire alla situazione locale. La sera partiamo

per Nis.

Venerdì 21 – Tomasevic Bojana, alla Min Fitip, una delle affidate,

arriva accompagnata dal nonno. Sì, lo riconoscono, è proprio lui, l’ex

direttore generale della fabbrica. Un signore simpatico e dimesso che

sorride senza alcun compiacimento e che firma la ricevuta della borsa

di studio per sua nipote come uno dei tanti operai che sono stati suoi

dipendenti. Arrivano tutti, pian piano. Ci salutano. Vorremmo scattare

qualche foto all’interno della fabbrica. Ci spiegano che non è

possibile. Lo sapevamo, ma abbiamo tentato. Probabilmente anche la

Min-Fitip è nell’elenco delle aziende, grandi e piccole, in vendita.

Nel luglio 2001 è stata creata, appositamente, un’Agenzia per le

Privatizzazioni e, secondo i dati ufficiali che ha pubblicato, nel

2002, su 366 aziende in privatizzazione, 274 sono state vendute con un

introito di 350 milioni di dollari (fonte: Banca Nazionale Serba). A

quanto saranno vendute la Min-Fitip e l’Elktronska Industria? Ogni

volta che una fabbrica o un’azienda sono alienate aumentano il numero

dei disoccupati, la povertà, le malattie, la disperazione, la sfiducia

nelle istituzioni, la rabbia, e chi più ne ha più ne metta. Si è poveri

e lo si diventa sempre di più.

A Nis siamo ospiti di amici a Niska Banja dove, nel pomeriggio, andiamo

a distribuire le “skolska stipendia” nella scuola “Ivan Goran Kovacic”.

Nell’atrio ci attendono i ragazzi. Non appena entriamo

cominciano a cantare. Sono tornati da poco da una “gara canora” tra

tutte le scuole della Serbia e sono arrivati secondi. Sono bravi!

Subito dopo cominciamo a consegnare le borse di studio. I problemi

anche qui non mancano: cerchiamo di capire come affrontare tre

emergenze. Un bambino leucemico, un secondo con problemi di crescita e

la terza operata al cuore e con una deformazione del palato.

Tenteremo di trovare tra i tanti amici dell’associazione una

possibilità di cura per il piccolo leucemico, un farmaco, il

Genotropin, per il secondo, e faremo controllare in Serbia la terza dal

medico che l’ha in cura e che, coincidenza positiva, è il figliolo di

una nostra cara amica serba. Ci capita di chiedere a molti affidati se

hanno corrispondenza con i loro amici italiani, alcuni dicono di sì,

altri no, altri ancora ci dicono di avere scritto ma di non avere avuto

risposta. Spieghiamo a tutti che come per loro non c’è alcun obbligo a

corrispondere con i loro sostenitori, così non c’è per chi li aiuta.

Comunque, la “skolska stipendia” è già un segno d’amicizia importante e

tangibile.

Sabato 22, riposo. Con alcuni amici parliamo del Kosovo partendo da una

domanda: cosa ne pensate della possibilità, prefigurata da Kostunica,

di una cantonalizzazione (un’ amministrazione serba e albanese

all’interno della provincia sul modello della divisione interna della

Bosnia ed Erzegovina) partendo dal presupposto che un “paradiso

multietnico” non è realizzabile? Quasi tutti sono convinti che è

impossibile convivere con gli albanesi, la maggior parte vede nella

cantonalizzazione l’unica strada, pochi pensano che si debbano mandare

(dimenticando gli accordi internazionali che lo impediscono) esercito e

polizia serbi. Molti parlano bene dei militari italiani che hanno

difeso i serbi e i loro monasteri, dove possibile. Tutti dimentichiamo

due cose: 1) la Ue continua a sostenere un’unica soluzione: una regione

multietnica; 2) contro la cantonalizzazione si è schierato il leader

albanese Rugova il quale ha detto che è una cosa impossibile. Rugova,

d’altra parte, ormai si comporta da verso e conciliante padrone di

casa: ha promesso ai serbi che farà ricostruire le loro case e le loro

chiese distrutte dai suoi amici lo scorso marzo.

Domenica 23. La famiglia Zuza parte per l’America. Profughi dalla

Bosnia, per la precisione da Konjic, tra Mostar e Sarajevo, da più

dieci anni vivono, madre, padre e due figli, un maschio, Miroslav, 15

anni, e una femmina (affidata), Jovana, 16 anni, nell’hotel “Serbja” di

Niska Banja. Il Commissariato per i rifugiati delle Nazioni Unite gli

ha dato questa possibilità. Partono per Las Vegas. Andiamo a salutarli,

insieme ad altri amici. Manca un’ora alla partenza. Piangono e noi con

loro. Ci tratteniamo il tempo per augurargli ogni bene. Lo meritano.

Hanno il coraggio della disperazione indispensabile per un passo del

genere. Vorremmo poter comunicare meglio di quanto non sappiamo fare

quello che percepiamo in loro: paura dell’ignoto e speranza in un

futuro migliore. Alle 8 prendono i loro bagagli. Arriva l’autobus per

Belgrado. La disperazione dei genitori, vecchi, che sanno di non poter

più vedere i loro figli; il pianto degli amici, giovani, che presto

dimenticheranno. Non rischiamo il patetico! Andiamo avanti!

Sono i ragazzi e i genitori della piccola scuola di Donja Vrezina, dove

andiamo dopo la partenza della famiglia Zuza, a farci dimenticare la

tristezza di queste prime ore di domenica. Mentre distribuiamo le quote

arriva, a piedi, un vecchio giornalista che vuole sapere qualcosa sul

nostro lavoro. E’ stato a Roma per diversi anni ed ora è rientrato in

Serbia e per arrotondare una pensione inesistente si è messo a fare il

“free-lance”. Fa foto e si informa. Il Comitato dei genitori della

scuolina ha preparato un gran rinfresco. Ci dicono che i serbi sono

fatti così: sono disposti a non mangiare pur di accogliere bene degli

amici. I bambini sono tutti lì ed anche i genitori che si prendono in

giro. Il “soggetto” è soprattutto il marito di una bella signora che

torna ogni due mesi dalla Slovenia dove è andato è riuscito a trovare

lavoro.

Facili allusioni, ma meno facile ironia quella del destino di Predrag:

trovare lavoro proprio dove avvennero i primi scontri, nel giugno del

1991, tra la Difesa territoriale slovena e l’armata jugoslava. Ma sono

passati 13 anni… e quasi tutti bambini che oggi hanno preso la “skolska

stipendjia” , per fortuna, a quel tempo non erano neanche nati. E

questa è la grande speranza, dimenticare e ricominciare!

Lunedì 24 – Fa un freddo cane! All’orizzonte vediamo le montagne

bulgare. Entriamo nell’Elektronska Indusrtrija, ex colosso locale e

nazionale che produceva elettrodomestici. All’E.I. le cose vanno ancor

peggio che alla Min- Fitip. Dei circa 20.000 dipendenti sono 800 quelli

che lavorano e 2.400 quelli a disposizione che sperano di essere

chiamati. Gli altri sono disoccupati. Le retribuzioni vanno dai 4.000

ai 18.000 dinari , vale a dire da 60 a 250 euro (a prendere 18.000

dinari sono soltanto 15 tecnici superspecializzati). Andiamo dai

bambini e dai genitori riuniti, come il solito, nella vastissima mensa.

Stiamo al buio: non si accende la luce e non c’è acqua. Ci si è

abituati a risparmiare in qualsiasi circostanza e per tutto. Cominciamo

a chiamare e, come abbiamo fatto, in tutte le scuole e le fabbriche,

spieghiamo che scatteremo due foto da spedire ai loro amici italiani.

Sono lì “docili” e pazienti. Cominciamo la consegna delle “skolska

stipendia” e, com’è avvenuto in tutti i posti dove siamo stati, anche

qui sul volto di questa gente rassegnazione. Parlando con loro sentiamo

che sono scoraggiati. Hanno poche speranze nel futuro e credono poco

nella classe politica che li governa. Sono sempre gli stessi (non

possiamo dargli torto), anche i partiti sono sempre gli stessi (anche

questo è vero), se capita la disgrazia di ammalarsi ci si può anche

rassegnare a morire (verissimo, tanto che tutt’intorno è tappezzato di

piccoli manifesti con l’annuncio della morte di qualcuno, spesso

prematuramente), il lavoro non c’è e i giovani non hanno un futuro. C’è

anche chi ha un sussulto e si arrabbia mentre parla, ma la maggior

parte sono quieti.

Da un caro amico, riusciamo ad avere, per la prima volta durante il

nostro viaggio, un documento ufficiale sottoscritto dal direttore

dell’Ufficio di collocamento. Proviamo a capirci qualcosa. Scopriamo

che i disoccupati a Nis, al 5 aprile scorso, sono 46.036 dei quali

24.488 donne. I posti disponibili, all’Ufficio di collocamento, sono

invece 5.540 (2.363 a tempo indeterminato e 3.177 a termine). Proviamo

a capire di quale tipo di lavori si tratta, ma non ci riusciamo.

Facendo i conti a “maniera nostra” la percentuale ufficiale dei

disoccupati a Nis, anche se non possiamo essere precisi perché non

conosciamo il totale della forza lavoro locale, dovrebbe essere di

circa il 40% (la Banca Nazionale Serba parla, per il 2003, di 33,7%).

Con i sindacalisti cerchiamo di capire poi la situazione politica. E’

praticamente dall’inizio del viaggio che andiamo in giro con un pezzo

di carta, dove abbiamo disegnato un semicerchio (il Parlamento serbo) e

scritto, cercando di collocarli nella loro posizione “fisiologica” , i

nomi dei partiti. Da questo schema esatto e semplice, ne viene fuori

un’immagine sbilanciata completamente a destra del Parlamento, anche se

il Partito democratico (ex Djindjic) lo scorso ottobre è entrato

nell’Internazionale socialista. A sinistra sembrerebbe essere presente

soltanto il Partito socialista serbo (ex Milosevic), messo storicamente

fuori gioco dagli eventi. Tutti, dopo aver osservato lo schema,

concordano che è una situazione sbagliata. Alcuni affermano che ci sono

dei piccoli partiti a sinistra, altri che hanno tentato di riempire

questo vuoto con un nuovo partito il “Labour”, ma per ora l’esperienza

è fallita, altri ancora che un partito di sinistra c’è, quello di

Milosevic. Tutti concordano su una cosa: non c’è nessuna figura

politica, a sinistra, capace di raccogliere consensi e democratizzare

così un parlamento sbilanciato e litigioso.

Martedì 25 – Partenza per la Bosnia. Nel primo pomeriggio siamo a

Rogatica alla scuola “Sveti Sava”. Sono 1.200 i bambini che la

frequentano distribuiti su tre turni (si comincia alle 7,20 e si

finisce alle 18 circa). Quest’anno hanno cominciato la scuola anche

bambini di sei anni. Qui, contrariamente a quanto avviene in Serbia (la

legge non ha trovato attuazione in seguito al cambiamento del governo),

la riforma della scuola è stata applicata. Siamo un po’ confusi!

Entriamo con bambini e genitori in un’aula per distribuire le quote di

affido. Una mamma sale al primo piano della scuola arracampicandosi con

l’aiuto di una stampella. Non sta bene, ma vuole salutarci egualmente.

Comincia la distribuzione delle “borse di studio”. Un Papà è solo: il

piccolo Mihali è all’ospedale. Pochi mesi fa è morta la moglie e ora il

bambino, paraplegico, sta accusando il colpo. Storie di disperazione.

Vorremmo evitare di raccontarle, ma sono testimonianze importanti. Ci

sono però anche i momenti lieti: l’accoglienza di genitori e ragazzi,

le letterine per gli affidatari, i piccoli regali fatti con il cuore e

il sacrifico, le foto fatte insieme.

Chiacchieriamo un po’ con il vice preside della scuola. Sarà il tempo

che passa, ma ci rendiamo conto che c’è una maggiore disponibilità, in

tutti, a parlare di più, ad affrontare argomenti da anni elusi (con

l’eccezione di Lukavica, dove il direttore, continua a dirci, in

italiano, “Milan, grande squadra”). Durante il colloquio annotiamo

delle cose significative dette dal nostro amico: “passo la frontiera

con la Serbia decine di volte al mese e ogni volta devo mostrare il

passaporto. Io sono serbo, come i serbi di Serbia! E’ umilitante!”.

“Davanti c’è una persona, ma dietro ce n’è sempre un’altra”. “In ogni

casa della Republika Srpska, anche la più sperduta, l’ospite è sacro e

ci sarà sempre per lui un pasto!”. Stereotipi? No.

Risaliamo in macchina e via verso Pale, ex roccaforte di Radovan

Karadzic, capo dei serbi di Bosnia e ricercato numero uno per crimini

di guerra. Pale, ex capitale della Republika scalzata dalla più

moderata Banja Luka. La casa dove siamo ospitati è vicinissima alla

chiesa e alla canonica dove il primo aprile scorso, un commando della

Sfor (veniamo a sapere casualmente da “alcuni italiani” che si sarebbe

trattato di militari americani che “non vanno per il sottile”) ha fatto

saltare la porta con una carica di esplosivo ferendo gravemente il

parroco e il figlio. “L’esplosione ha frantumato i vetri delle

abitazioni circostanti (ad una sessantina di metri perché chiesa e

canonica sono al centro di una piazza-giardino) e non ci si poteva

affacciare perché i militari che circondavano gli edifici puntavano i

fucili”, ci dicono. Ma lasciamo stare queste cose!

Mercoledì 26 – La scuola “Pale” di Pale nel 2005 compirà cent’anni! Non

pochi! I bambini affidati sono una trentina e quasi tutti per arrivare

a scuola devono percorrere, ogni giorno, diversi chilometri a piedi. Ad

attenderci c’è anche Donato, un socio di San Donato Milanese, che è

venuto a trovare il suo “figlioccio”, Bosko, ed è ospite della famiglia

del bambino. E’ entusiasta di questa esperienza e ci parla di come è

stato accolto e della situazione difficile della famiglia. Per lui è

stata organizzata una gran festa alla quale hanno partecipato tutti i

vicini.

Ognuno ha portato qualcosa e, in poco tempo, è stato allestito un vero

e proprio banchetto! Cominciamo a distribuire le borse di studio e

facciamo le foto. Al direttore chiediamo, come abbiamo fatto in tutte

le altre città, schede di nuovi ragazzi da affidare. Finiamo presto.

Vorremmo andare a fare una camminata nei boschi. Ce lo sconsigliano.

Ancora troppi posti contaminati da mine e ordigni inesplosi. Notizia

ufficiale: in Bosnia sono 1.366 i centri abitati contaminati e, secondo

il Centro per lo sminamento, sono registrati oltre 10.000 campi minati.

Meglio evitare per non correre il rischio di aumentare il numero delle

vittime, 1.048, registrate dalla fine della guerra (1995).

Nel pomeriggio andiamo a Lukavica, enclave serba alla periferia di

Sarajevo. Il direttore della scuola “Sveti Sava”, milanista

“sfegatato”, è alle prese con il Consiglio d’istituto e ci accoglie il

suo vice. Entriamo nell’aula dove ci aspettano i bambini con i

genitori. Tra loro Blazic Sasa, “recordboy”: undici tra fratelli e

sorelle. A vedere il papà, un poco malridotto, zoppica e si sostiene

con una stampella, non ci sembra possibile che sia così “prolifico”. Ci

asteniamo da commenti, anche se alcuni suggerimenti gli servirebbero.

Distribuiamo le quote e riceviamo tre baci da ciascun affidato. Arriva

anche il direttore e, dopo i saluti, ci chiede subito se vogliamo

aiutarlo a costruire una palestra. Infatti, la scuola di Pale è un dono

della cooperazione giapponese e loro costruiscono le scuole senza

palestre. Gli diciamo che siamo una piccola associazione che non può

permettersi una spesa del genere. Di fronte al diniego ci svela che ha,

comunque, un probabile donatore. E’ una vecchia volpe mr. Milovan. Uomo

eccezionale, capace di fare il bene dei suoi alunni senza esporre se

stesso e chicchessia. Cauto al punto di rispondere “tutto OK” alla

banale domanda: “come vanno le cose a Lukavica?”. Ma basta dare

un’occhiata ai bambini e ai genitori per capire che le cose non sono

per niente OK a Lukavica che, come tutta la Republika Srpska, ha

problemi enormi: 43% di disoccupazione, miseria e fame, sporcizia e

disperazione. Giovedì ripartiamo per l’Italia!

(srpskohrvatski / english)

---

http://www.iwpr.net/index.pl?archive/bcr3/bcr3_200405_500_4_eng.txt

NOSTALGIA GROWS FOR TITO’S LOST WORLD

Social and economic instability prompt many Balkan citizens to yearn

for a time of order and prosperity.

By Marcus Tanner, Muhamet Hajrullahu in Pristina, Drago Hedl in Osijek,

Dino Bajramovic in Sarajevo, Mitko Jovanov in Skopje, Vladimir Sudar in

Belgrade and Tanja Matic in Subotica

Kaqusha Jashari, head of the Social Democratic Party of Kosovo, has

fond memories of the days when she carried the baton for Yugoslavia’s

late strongman, President Josip Broz “Tito”.

A prominent Albanian politician in the communist regime, she was

selected for the honour of carrying a baton containing a message from

the nation’s youth to the president in a relay from Slovenia in the

north to Kosovo and Macedonia in the south.

The culmination was the handing of the baton to the president in the

army stadium in Belgrade amid cheering crowds on his birthday on May

25. “The celebration of worship for Tito fitted in perfectly with the

education we had at the time,” Jashari recalled. “It was everyone’s

celebration, a festival of youth.”

Jashari’s views are less unusual than many think. While four of the six

Yugoslav republics are now independent states and Kosovo – still

technically [sic] part of Serbia– is desperate to become the fifth,

many inhabitants of the former federation, especially the elderly and

those from the poor south, recall Yugoslavia with nostalgia.

For them it was a time when food and jobs were plentiful, crime was

low, ethnic differences were downplayed and difficult political

decisions were left to the uniformed Marshal, whose stern features

stared down from thousands of portraits in offices, railways stations,

shops and homes.

“I was rich in Tito’s time, there were factories and handicraft

businesses – we had jobs, we had everything,” mused 84-year-old Mehdi

Shabani from Pristina. “The standard of life was far better,” added

Osman Krasniqi, 62, also a resident of the Kosovo capital. “With a low

salary you could build a house - you can’t do that now.”

Kosovo was the least Yugoslav area of all, for the simple reason that

it was the least Slav. “Albanians were less connected with Yugoslavia

than the other nations because they were the only non-Slavs. All we had

in common was the communist ideology, which was less personal than

sharing a language, culture and religion,” said Jashari.

Among the neighbouring Slavs of Macedonia, where locals not only got

jobs and food but their own republic, affection for Tito is far

greater. Whereas Tito’s once ubiquitous name has been torn down from

most streets and squares in ex-Yugoslavia, in the Macedonian capital of

Skopje, the largest and most elite school still sports the title “Josip

Broz Tito” and each May 25 it honours its patron saint with a folk

dance and a flower-laying ceremony.

For many Macedonians, poverty-stricken independence has proved a poor

exchange for a secure life in a large Slav federation. “There was no

division between rich and poor, everybody could afford to go to school

and have a home and a job,” maintained Makedonka Jancevska, 62, a

retired Macedonian language teacher.

“Patriotism was fostered on a broader scale; it meant respect of

everything related to the uniqueness of all the nations and

nationalities that were part of Yugoslavia.”

“The standard of living we had provided us with economic security and

many social benefits,” recalled Petar Mojsov, 46, a Macedonian

accountant. “Everyone could afford a flat and a car. I travelled to

Italy for shopping. I went to Greece for a vacation whenever I felt

like it.”

Tose Nackov, an electrical technician, remembers when whole towns in

Macedonia turned out to welcome the birthday baton that youths like

Kaqusha Jashari of Kosovo once proudly carried.

“We were impatient for the day when it would visit our town,” Nackov

said. “It was like a holiday and we would all gather in the square to

welcome it and see it off on its way to another town.”

Enthusiasm for Tito’s memory is so strong in Macedonia that last year a

new association was set up under Slobodan Ugrinovski to celebrate his

life. His 6,180 club members go on trips to (the few) institutions

still bearing Tito’s name and visit the main shrines, Tito’s final

resting place in Belgrade’s House of Flowers and his birthplace in

Kumrovec, Croatia.

As in Macedonia, the hapless inhabitants of war-torn, economically

ruined Bosnia and Herzegovina cannot help but contrast life under Tito

with what they have now. To Bosnians, Tito's name is widely associated

with “the good old times”.

Far from dimming, the cult of Tito there grows ever stronger. When the

authorities recently tried to rename the main street in Sarajevo after

Alija Izetbegovic, Bosnia’s first post-independence president, the

city’s inhabitants rose up, hanging a billboard across the boulevard

with Tito’s image on it and the slogan “This is the Street of Marshall

Tito”. Months after the initiative collapsed, this billboard remains.

“The young are turning to Tito because he personified prosperity,” said

Adnan Koric, a member of the Bosnian Association of Josip Broz Tito.

“They know that only during Tito’s time we constantly progressed for 45

years in every aspect of social and economic life.”

Koric believes Bosnians yearn for the time when they did not need

several currencies and visas to cross what was once a single territory.

“Now we cannot spend a tank of fuel driving in a straight line without

getting six visas first,” Koric joked.

In Sarajevo, Tito’s image has returned from the cellars and second-hand

shops to popular bars and restaurants. At Tito Bar, a popular haunt of

students, young people and professionals, walls are covered in Tito

insignia and photographs while waiters wear uniforms bearing Tito’s

still-familiar signature. “I come here to think about and live in the

past,“ said 26-year-old Amel. “Whatever some may say, our past was

brighter than our future.”

While Bosnia and Macedonia lost much and gained little from the fall of

Tito’s Yugoslavia, memories are less rosy in neighbouring Serbia and

Croatia. For more than a decade under the rule of Slobodan Milosevic,

Tito was demonised in Serbia as a Croatian enemy who had plotted the

Serbs’ downfall in Yugoslavia.

[NOTE: In reality, Tito was less demonized in Milosevic's era than he

is demonized now in Serbia; and he has been demonized much more in

Croatia than in Serbia since 1991 (think e.g. to the "Bitburg"

propaganda, and to the vehement anti-communism of HDZ). IWPR's comment

on "Milosevic's era" has much more to do with "political correctness"

in front of the western public opinion than with facts. CNJ]

But even in Serbia, the disappointments of the past decade, including

lost wars and collapsing living standards, have changed minds. Misa

Djurkovic, of the Belgrade Institute for European Studies, says a

growing nostalgia for Tito’s era is related to more than sorrow for

lost living standards.

"Yearning for [the old Yugoslavia] is also a yearning for order and

dignity,” he said. “Our ‘soft’ communist dictatorship was, after all, a

serious, well-established system in which there were none of the

robberies, chaos and anarchy that are now sadly typical.”

Djurkovic believes this nostalgia has even spread to some of the

younger generation, “Youngsters today see in Yugo-nostalgia an

instrument of protest against the rotten legacy of the Nineties, which

they have inherited.”

There is certainly no sign of the House of Flowers shutting its doors

to pilgrims, though it is a more neglected site than it was in the

Eighties, when foreign diplomats and visiting heads of state came to

the grave to pay their respects as a matter of course.

But if the crowned heads of state and presidents no longer troop past

Tito’s mausoleum, war veterans, communist party members and

non-governmental organisations, NGOs, still return on the late leader’s

birthday. Svetlana Ognjanovic, the House of Flowers spokeswoman, said

she expected up to 2,000 people for this year’s commemoration,

including a large party of Slovenian Hell’s Angels (the motorcyclists

have made an annual pilgrimage to the site since 2000).

The head of the Tito Centre NGO, retired army general Stevan Mirkovic,

also marks the day with dinners of partisan-style beans and a

re-enactment of the baton ceremony. And in Serbia’s far north, Blasko

Draskic, 73, has gone as far as you can in a campaign to restore Tito’s

memory, opening a theme park named “Yugoland” near the border town of

Subotica.

Mini-Yugoslavia has several of the geographical attributes of the

former Yugoslavia, including a hill named after its highest peak, Mt

Triglav, in Slovenia. Old flags with red stars flutter around the

entrance, while Tito’s portrait adorns every wall, showing Tito

hunting, playing the piano, reading, dancing and paying state visits.

Blasko even issues citizenship papers for Yugoland to visitors, and has

enrolled 2,500 so far.

Draskic says the abolition of the name “Yugoslavia” was a crime. “The

government [of Serbia and Montenegro] has killed off the name of the

best country, Yugoslavia, the last thing that reminded us of former

Yugoslavia, but without asking people for their consent,” he said. “I

had to save it for all Yugo-nostalgic people who can come here freely

to enjoy memories of Tito’s time.”

Although Draskic claims visitors are all of ages, the photographs of

celebrations held in Yugoland suggest Yugo-nostalgia is mainly a

middle-aged or elderly phenomenon.

Among the young people of all republics, interest is small or confined

to a ironic cult, a bit like those ex-east Germans who mock-celebrate

their communist past by driving Trabant cars and sporting badges with

communist slogans.

Aca Bogdanovic, 32, from Belgrade, said he only respected Tito “because

he was the greatest hedonist of the 20th century” - hardly the kind of

compliment real devotees appreciate. That kind of ironic appreciation

is equally evident in Tito’s Croatian homeland where only a handful

remain faithful to his political ideas, while a much larger and younger

group enjoy experimenting with Titoist motifs.

“It is mostly the young who buy these t-shirts - those who weren’t even

born when Tito died!” remarked a salesman in Osjek, in northeast

Croatia of his stack of t-shirts with Tito’s face on them.

Zagreb sociologist Drazen Lalic says that while only a few older people

can be described as truly Yugo-nostalgic, a growing interest in Tito

personally and in the country he once ruled stems from the fact that

Croatia is more at ease with itself now than it was ten years ago.

“After years of hearing that we belong solely to the Mediterranean or

Central European culture, we are now facing the fact that Croatia also

belongs to the Balkan cultural circle,” said Lalic.

“Yugo-nostalgia exists but people do not grieve for Yugoslavia as their

former state,” said Milanka Opacic, of the Social Democratic Party.

“They grieve for the quality of life they had. They think they were

much better off, safer, had a better standard of living and better

health protection than they now have.”

The plain fact is that Yugo-nostalgia no longer antagonises anyone

because no one seriously believes Yugoslavia will ever be recreated. In

Croatia, as the country heads towards the European Union,Yugoslavia is

seen as a thing of the past - an unsuccessful project that cannot and

will not be restored. As a result, Yugo-nostalgics in Croatia are now

viewed as romantics, rather than the enemies of the state they were

called during the era of Croatia’s nationalist, leader Franjo Tudjman.

Marcus Tanner is IWPR Balkan editor/trainer; Dino Bajramovic is culture

editor at the Sarajevo weekly, Slobodna Bosna; Vladimir Sudar and Mitko

Jovanov are journalists with the Belgrade weekly Reporter and the

Macedonian daily Dnevnik respectively; and Muhamet Hajrullahu, Drago

Hedl and Tanja Matic are regular IWPR contributors.

---