Informazione

Conferenza

Mercato della guerra: dall'Iraq al Piemonte

Guerra e globalizzazione

Lunedì 31 maggio 2004 ore 12:30

Aula Magna Politecnico di Torino

corso Duca degli Abruzzi 24

-Quale futuro per l'Iraq? - Sherif El Sebaie, redattore di AlJazira.it

-Conflitti dimenticati - Fulvio Poglio, redattore di Warnews.it

-Il mestiere delle armi in Piemonte - Francesco Bonavita, FIOM CGIL Alenia

-Ideologia del libero mercato, guerra e movimento per la pace -

Vittorio Agnoletto (Forum Sociale Mondiale)

Ore 14:30

Proiezione dei film

-`L'arcobaleno e il deserto - Emergency in Iraq' di Antonio Di Peppo e

Guido Morozzi

durata 25 minuti

-`Fotoricordo' di Tamara Bellone e Piera Tacchino durata 35 minuti

con interventi su "Cultura di pace e diritti umani" di collaboratori

di Peacereporter, Emergency, CGIL Lavoro e Società, AlJazera,

Coordinamento Nazionale per la Jugoslavia, R.S.U. Politecnico.

Mercato della guerra: dall'Iraq al Piemonte

Guerra e globalizzazione

Lunedì 31 maggio 2004 ore 12:30

Aula Magna Politecnico di Torino

corso Duca degli Abruzzi 24

-Quale futuro per l'Iraq? - Sherif El Sebaie, redattore di AlJazira.it

-Conflitti dimenticati - Fulvio Poglio, redattore di Warnews.it

-Il mestiere delle armi in Piemonte - Francesco Bonavita, FIOM CGIL Alenia

-Ideologia del libero mercato, guerra e movimento per la pace -

Vittorio Agnoletto (Forum Sociale Mondiale)

Ore 14:30

Proiezione dei film

-`L'arcobaleno e il deserto - Emergency in Iraq' di Antonio Di Peppo e

Guido Morozzi

durata 25 minuti

-`Fotoricordo' di Tamara Bellone e Piera Tacchino durata 35 minuti

con interventi su "Cultura di pace e diritti umani" di collaboratori

di Peacereporter, Emergency, CGIL Lavoro e Società, AlJazera,

Coordinamento Nazionale per la Jugoslavia, R.S.U. Politecnico.

From: "Roland Marounek"

Date: Mon, 24 May 2004 00:15:54 +0200

To: <alerte_otan @ yahoogroupes.fr>

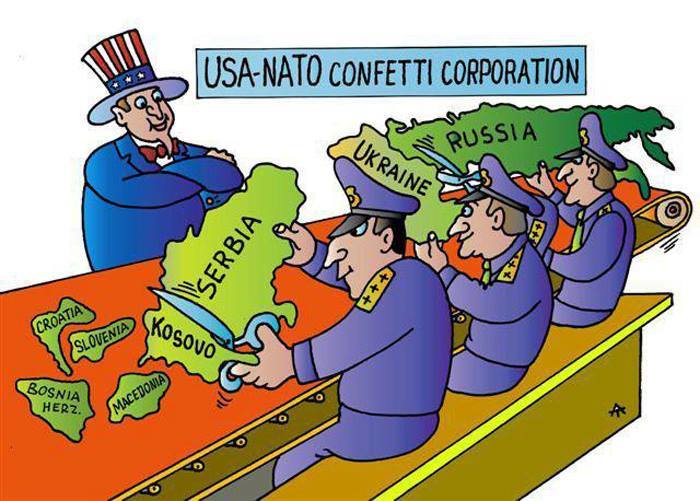

Subject: [alerte_otan] DE LA YOUGOSLAVIE A L'IRAK : L'EUROPE FACE AUX

GUERRES D'AUJOURD'HUI ET DE DEMAIN

DE LA YOUGOSLAVIE A L’IRAK

L’EUROPE FACE AUX GUERRES D’AUJOURD’HUI ET DE DEMAIN

BILAN ET RESPONSABILITES DES INTERVENTIONS MILITAIRES OCCIDENTALES

Un ancien Ministre belge occupant d’importantes fonctions lors du

déclenchement des guerres balkaniques reconnaît avoir été alors

conditionné par la médiatisation ambiante de ce conflit et dénonce

aujourd’hui les grandes impostures qui servirent à justifier

l’agression de l’OTAN contre la Yougoslavie. Il dialoguera et débattra

de la scène internationale et des responsabilités actuelles et passées

de l’Europe avec un économiste égyptien, observateur lucide et engagé

de la situation internationale, et avec le Directeur de la revue

«Alternatives Sud» et co-fondateur du Forum Social Mondial, à

l’invitation de l’Espace Marx.

VENDREDI 28 MAI A 19H30 : CONFERENCE-DEBAT

A l’Espace Marx : 4, rue Rouppe – 1000 Bruxelles

Avec la participation de :

Samir AMIN

(professeur universitaire et écrivain égyptien, Directeur du Forum du

Tiers Monde)

Guy SPITAELS

(ancien Ministre, auteur du livre « L’improbable équilibre »),

François HOUTART

(Directeur du Centre Tricontinental et Président du BRrussels Tribunal)

Modérateur : Vladimir CALLER (journaliste)

P.A.F. : 4 euros

(étudiants, chômeurs : 1,50 euros)

Attention : LA SEANCE COMMENCERA A 19 HEURES 30 PRECISES.

SOUS LES AUSPICES DE LA FONDATION JACQUEMOTTE

(fjj.timmermans.eliane @ skynet.be)

Pour vous désabonner de cette liste de diffusion, envoyez un email à :

alerte_otan-unsubscribe@...

Pour retrouver les messages précédemment envoyés:

http://fr.groups.yahoo.com/group/alerte_otan/messages

Cette liste est gérée par des membres du Comité de Surveillance OTAN.

Les opinions éventuellement exprimées n'engagent que les auteurs des

messages, et non le CSO.

Date: Mon, 24 May 2004 00:15:54 +0200

To: <alerte_otan @ yahoogroupes.fr>

Subject: [alerte_otan] DE LA YOUGOSLAVIE A L'IRAK : L'EUROPE FACE AUX

GUERRES D'AUJOURD'HUI ET DE DEMAIN

DE LA YOUGOSLAVIE A L’IRAK

L’EUROPE FACE AUX GUERRES D’AUJOURD’HUI ET DE DEMAIN

BILAN ET RESPONSABILITES DES INTERVENTIONS MILITAIRES OCCIDENTALES

Un ancien Ministre belge occupant d’importantes fonctions lors du

déclenchement des guerres balkaniques reconnaît avoir été alors

conditionné par la médiatisation ambiante de ce conflit et dénonce

aujourd’hui les grandes impostures qui servirent à justifier

l’agression de l’OTAN contre la Yougoslavie. Il dialoguera et débattra

de la scène internationale et des responsabilités actuelles et passées

de l’Europe avec un économiste égyptien, observateur lucide et engagé

de la situation internationale, et avec le Directeur de la revue

«Alternatives Sud» et co-fondateur du Forum Social Mondial, à

l’invitation de l’Espace Marx.

VENDREDI 28 MAI A 19H30 : CONFERENCE-DEBAT

A l’Espace Marx : 4, rue Rouppe – 1000 Bruxelles

Avec la participation de :

Samir AMIN

(professeur universitaire et écrivain égyptien, Directeur du Forum du

Tiers Monde)

Guy SPITAELS

(ancien Ministre, auteur du livre « L’improbable équilibre »),

François HOUTART

(Directeur du Centre Tricontinental et Président du BRrussels Tribunal)

Modérateur : Vladimir CALLER (journaliste)

P.A.F. : 4 euros

(étudiants, chômeurs : 1,50 euros)

Attention : LA SEANCE COMMENCERA A 19 HEURES 30 PRECISES.

SOUS LES AUSPICES DE LA FONDATION JACQUEMOTTE

(fjj.timmermans.eliane @ skynet.be)

Pour vous désabonner de cette liste de diffusion, envoyez un email à :

alerte_otan-unsubscribe@...

Pour retrouver les messages précédemment envoyés:

http://fr.groups.yahoo.com/group/alerte_otan/messages

Cette liste est gérée par des membres du Comité de Surveillance OTAN.

Les opinions éventuellement exprimées n'engagent que les auteurs des

messages, et non le CSO.

(deutsch / english / srpskohrvatski)

[ Il settimanale tedesco DER SPIEGEL, in un recente articolo dai toni

allarmati sulla esplosione dei pogrom lo scorso marzo e sul perdurare

delle violenze degli irredentisti pan-albanesi, definisce semplicemente

"conigli" i soldati tedeschi dell'UNMIK apparentemente incapaci di

difendere le persone ed il patrimonio storico-artistico della

provincia... ]

THE RABBITS OF KOSOVO

DIE HASEN VOM AMSELFELD

ZECEVI SA KOSOVA

(R. Flottau, O. Ihlau, A. Szandar, & A. Ulrich - DER SPIEGEL)

=== ENGLISH ===

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/decani/message/81752

Der Spiegel, Germany

May 3, 2004

German soldiers: The Rabbits of Kosovo*

*In German Original: Amsfeld - Field of blackbirds (in Serbian - Kosovo

Polje)

Serious criticism of the German KFOR contingent in the restless

province of Kosovo: German UN policemen accuse the Bundeswehr (German

Army) of humiliation and defeat during violence by Albanian extremists.

By Renate Flottau, Olaf Ihlau, Alexander Szandar, Andreas Ulrich

The voice of the German UN policeman betrayed panic. "When will you

finally came," pleaded the man over the radio, "For God's sake, we

urgently need support."

In front of the building of the UN police in the town of Prizren, in

the sector of the German KFOR peacekeeping force in the restless

province Kosovo, the unbridled mass of Albanian nationalists raged for

hours. They set out on a hunt for Serbs and their alleged protectors.

Stones flew and Molotov cocktails, flames covered the light brown earth

next to the turned over and destroyed police cars. Confronted with this

orgy of hate, several dozen UN officials had sought sanctuary in the

police station and barricaded themselves. Many were bleeding.

"Come quickly, we need assistance," repeated the German policeman again

and again over the radio. But nobody came and the military sent no

assistance. The UN employees were probably saved from the worst only by

the circumstance that on the second day of the March riots, the madness

of the Albanians turned toward the burning of the church of Sveti Spas

(Christ the Savior) and the settlement where 2,000 Serbs had lived

before the war.

During the recent riots in Kosovo 19 people were killed, 8 Serbs and 11

Albanians, the latter primarily in self-defense by threatened UN

policemen and KFOR soldiers. According to the balance sheet of UNMIK,

the UN civil administration of this international protectorate, there

were about 900 injured, among them 65 members of the international

forces. Twenty-nine churches and monasteries, as well as about 800

houses belonging to the Serbian minority were destroyed, while several

thousand Serbs saved themselves by fleeing.

With these acts of violence probably the last illusions of a possible

reconciliation of the national communities and the building of a

multiethnic democracy have been destroyed. In the war for human rights

in 1999 NATO bombers expelled the murderous military machinery of

Serbian ruler Slobodan Milosevic from Kosovo and enabled the return of

800,000 Albanian refugees. Five years later the international community

must recognize that it has gambled away its moral and military victory

and that its ambitious mission is in danger of failing. Many of the

victims of yesterday are the criminals of today. Like the former

Belgrade despot, Albanian extremists are now carrying out bloody ethnic

cleaning in order to create a Serb-free state of Kosovo - centering on

the historic Field of Blackbirds (Kosovo Polje) where an army of

Serbian knights bled in the battle against the Turks in 1389 and

created the myth of the Serbs as victims.

"We reacted quickly," lieutenant general Kammerhoff said of the

engagement of the 20,500 KFOR troops, which he has commanded since last

October. German defense minister Peter Struck also highly praised the

"prudent behavior" of his 3,600 soldiers: "They reacted rationally,

preventing an escalation and thus protecting human lives."

That is Berlin's version. Reports of eyewitnesses in Prizren, however,

reveal a completely different picture. Not only Serbs, but also UN

officials, troops from other KFOR contingents, Albanian human rights

activists and independent journalists accuse the Bundeswehr of failure

and even cowardice. The Bundeswehr played a sad, perhaps even very

shameful role in restraining the violence. The German soldiers ran

away, hiding like rabbits in their barracks and emerged again with

armored vehicles only once the Albanian crowd had calmed down, having

completed its work of destruction. So far no other such harsh

accusation has been heard against the international missions of the

German military.

The failure to stop this naked terror reminded some Balkans observers

of Srebrenica: After the fall of the Bosnian city in July 1995, the

Dutch UN officer Karremans was toasting the Serb general Mladic while

thousands of Muslims were removed for execution.

"Their intervention was a failure, they should withdraw," said Bishop

Artemije of the Serbian Diocese of Kosovo and Metohija, speaking of the

Germans. And Father Sava Janjic, the spokesman for Decani monastery,

added: "After what the Germans have done in two world wars, we want

them to leave the Balkans."(*)

But the German UN policemen, too, felt abandoned by the German

soldiers. Herbert Fischer Drumm, the police pastor in

Rhineland-Palatinate, discovered "signs of trauma" in some of the 278

German policemen with whom he personally spoke, "because their calls

for assistance to KFOR fell on deaf ears". Many officials, the minister

said, ask themselves why the soldiers were there in the first place if

they could not offer them assistance.

Reports of the frustrated policemen have been presented, in the

meanwhile, to UNMIK. Their Finnish boss Harri Holkeri, Albanian

newspapers report, allegedly had a bitter dispute with the KFOR

commander Kammerhoff. The reports are now being evaluated. "KFOR must

reexamine its concept of security," demanded Saxonia-Anhalt interior

affairs minister Klaus Jeziorsky (CDU), who returned last week with his

colleague from Hamburg Udo Nagel from a visit to Kosovo. Nagel is also

of the opinion that "KFOR must able be to protect UN employees".

After an inspection tour of Kosovo on 5 and 6 April, the chairman of

the German task group for international police forces, North

Rhine/Westphalia police inspector Dieter Ve, summarized the results of

his findings in a report and sent it to the German interior ministry

and provincial interior ministers. His conclusion: "During violent

unrest KFOR is not adapted to calming the situation. Cooperation

between Kfor and Unmik is not coordinated."

In Prizren "despite constant requests for assistance to KFOR" not one

soldier appeared in order to support the police. KFOR "proved to be

unable to carry out its assigned tasks".

UN police commissioner Stefan Feller is also quoted in the report as

saying that KFOR is not up to calming of riots, that the military not

sufficiently trained and prepared. KFOR could not guarantee "security

tasks assigned to it and provide protection for the Serbian population".

"For weeks a steady increase in tension could be felt," German police

officers in Prizren told Der Spiegel. They do not want to give their

names and rank because they are presently under UN command and any

statement could have legal consequences.

The pressure was concretely directed against the some 100,000 Serbs

remaining in the province and against UNMIK, which has began to conduct

an investigation against the former Kosovo Liberation Army for war

crimes. The rhetoric of the Albanian nationalists became more sharp, as

did the political graffiti written on the walls. "It was clear that

something was going to happen," said one official, "we just didn't know

when." Eruptions of Albanian violence during which Serbian villages,

monasteries and churches were systematically attacked have occurred on

several occasions since the end of the war. However, earlier KFOR

peacekeeping forces with 50,000 troops were considerably more agile.

"We are expected to work miracles," complained the very first UN

administrator, Bernard Kouchner of France, after periodically

reoccurring outbursts of ethnic hate.

This time the – unproven – claim that two Albanian boys were chased by

Serbs into the river Ibar and drowned led to the explosion of violence.

First in Kosovska Mitrovica and then in almost every other town and

city in the crisis-ridden province, including Prizren.

There, according to the debriefing of German policemen, about thousand

demonstrators marched through the city center on 17 March, chanting

"UCK, UCK" (KLA, KLA) and "UNMIK, ARMIK" (Unmik is the enemy). People

from the surrounding villages joined them; obviously they were

Islamists, recognizable by their long beards.

At 5:30 p.m. the first houses in the old part of the city began to

burn. The Serbian seminary was set on fire with the approval of the

gathered residents, stones flew at the civil administration building,

automobiles were destroyed. Not a sign of KFOR, although anxious

eyewitnesses requested intervention by German officers several times by

telephone.

Only when the flames threatened to spread to the surrounding houses did

Argentine UN police special forces approach, remaining at a safe

distance of 300 meters. Their attempt to disperse the crowd with

teargas was countered with a hail of stones and bottles. The South

Americans dropped their clubs and protective shields and fled.

The German KFOR appeared for the first time when the rioters took a

fire truck and drove to the UNMIK building. The appearance of the

military had an obvious effect. The mass continued on, nothing stopping

it in its march of destruction.

Between 6 p.m. and 9 p.m. the mass rioted in the old part of town on

the slope beneath the ruins of a Byzantine castle. The houses of

Serbian refugees were set on fire. A company of KFOR soldiers, guarding

the Serbian church of St. George from behind barriers of sandbags, fled

with the clergy and the remaining Serbs into the barracks. The

demonstrators applauded, set fire to the church and 56 more houses and,

in the end, the Orthodox church of the Holy Virgin of Ljevis, not far

from the municipal building. German defense minister Struck once had

said that this church is "a symbol of lasting peace brought by our

mission".

Some extremists continued on up the river Bistrica to the monastery of

Holy Archangels. The approach road could have been easily blocked with

a few armored vehicles, especially since master sergeant Udo Wambach

and 19 soldiers of the Bundeswehr were stationed in the 14th century

monastery.

About 200 demonstrators sent a delegation under a white flag to the

Germans and ensured them that nothing bad would happen to them, that

"we only want to burn down the monastery". The KFOR protectors

evacuated six monks and their two visitors to their armored vehicles

and drove them to the other side of the Bistrica. The monastery was

then burned down.

Master sergeant Wambach was expressly commended for his "outstanding

act" in mid-April by the deputy defense minister, Walter Kolbow, during

his visit to Prizren. No medal was issued but nevertheless a note was

included in his personnel file. According to the commendation, the

sergeant avoided "by his prudent behavior and courageous action, an

escalation of violence, preventing bloodshed and protecting the human

lives entrusted to him".

When night fell, the fire from the burning of the old part of town

illuminated the sky over Prizren. The next morning, on Thursday, March

18, smoke still could be seen rising above the rubble. But now

everything was calm.

At about 12:30 p.m. the mass again went into action. Since all Serbian

institutions were destroyed, the hatred of the Albanians was directed

now against the municipal administration, the UN civil administration

and the two police stations.

The first attacks began at about 3:00 p.m. and targeted the police

station in the city center. Calls for assistance directed to KFOR

remained unanswered. Stones flew at the house, automobiles were

overturned, no soldiers anywhere were to be seen. KFOR obviously had

not used the time to consider the reexamine its concept of engagement

in order to prevent renewed unrest.

This was followed by an attack on the police headquarters only a

kilometer away. Policemen from different nations, including Germans,

were exposed to a constant hail of stones and Molotov cocktails. The

extremists were receiving support and refills from a nearby gas

station. Gunshots rang out.

"We pleaded with KFOR for assistance," reported one official. "They

told us that the soldiers were on their way but nothing happened." The

one thing which the policemen was a military vehicle from which

soldiers on a nearby hillside were observing the orgy of violence. "I

felt like scum," wrote a German policeman in his report. "The worst

thing," said another official, "is that the rioters achieved their

goals. The soldiers merely watched the progression of ethnic cleansing.

Our mission failed."

Only when the rioters in Prizren began to throw grenades into the UNMIK

building did German KFOR intervene. It sent a few armored vehicles and

the situation calmed down immediately.

The German contingent in Prizren did not report any injuries during the

two days of chaos. That is really commendable. Other KFOR contingents,

including the Italians, the Greeks and the French, reported numerous

injuries. Didn't these KFOR soldiers have the same orders as the

Germans? Did they act on their own initiative or were they simply more

courageous?

The Swedish battalion which attempted to protect the Serbs in the

village of Caglavica from the Albanian arsonists had 14 men inured. "We

were surprised and now we are waiting for the next round," junior

officer Andersson admitted to reporters. "We will pay these Albanians

back." In Mitrovica, where most of the casualties occurred, French KFOR

troops and UN police prevented the Albanians from arriving in the

Serbian, northern part of the city.

Why was it not possible to protect the monasteries in Prizren, a

journalist from the Canadian "Chronicle Herald" asked some German

officers. Their response: "It is not in our mandate to hurt innocent

civilians in order to protect an old church."

Colonel Dieter Hintelmann, the commander of the German KFOR contingent

in Prizren, defended himself with a similar line: "We acted exactly

according to our regulations.

Protection of buildings is not the task of the Bundeswehr in Kosovo. It

is allowed to fire only in self-defense."

Every soldier has a little pocket edition of the "Rules of Engagement".

They do not foresee the protection of buildings with the use of weapons

and shooting at demonstrators who are throwing Molotov cocktails at

churches or monasteries. The chapter on "rules for the use of military

force" gives the soldier clear recommendations: "You have the right to

repel attacks against KFOR personnel, KFOR material and persons under

the protection of KFOR." It is precisely this right, the German

policemen criticize, that the Bundeswehr in Prizren unfortunately

failed to use.

"The leaders of the demonstrations knew exactly that as long as they do

not attack us, we cannot shoot," said Hintelmann. An authorization for

the raging mob? "I cannot order soldiers to shoot into a crowd of

people which includes children," said the officer. "Columns of

demonstrators including women and children blocked the military base

and prevented reinforcements."

The officer has received strong support from his superiors back at home.

"The essence of our task is to protect human lives," said the mission

command administration in Potsdam, where Hintelmann's military

commanders are located. The unit was right to concentrate "on

protecting the Serbian population and UN employees." Although German

policemen also waited for it in vain.

Accusations that the Germans withdrew in cowardly fashion are

"completely absurd" for the chief of the Bundeswehr. According to

effective German law, the military is not allowed to use teargas or

fire rubber bullets at crowds, Struck explained, merely "to fire

warning shots into the air".

The foreign affairs minister ("I am not one of those people who accuse

soldiers") has also protected the troops. "Our soldiers have carried

out a lot of things under substantial risk and enormous pressure," said

Joschka Fischer (Green Party), "They have saved many people and this

prioritization was correct."

However, both the Germans in Prizren and in Berlin grant one thing:

They were surprised by the rebellion, which in just a few hours spread

throughout the entire area of conflagration. Kfor reconnaissance units

and the secret services of several countries failed.

At the same time, none other than the Germans praised themselves for

their outstanding contacts with the population, in part thanks to a

historical bonus: during the World War II, the Albanians supported the

Wehrmacht in the fight against Serbian partisans and even sent Hitler

an entire SS division named after their national hero, Skenderbey(**).

Anyone "who attacks Serbian enclaves or cultural properties in Kosovo

in the future will confront Kfor," general-lieutenant colonel

Kammerhoff announced, suggesting by the firmer posture an implicit

acknowledgement of failure. An internal "progress report" speaks of

"the need to act in order to bring riots under control".

Minister Struck would now like to equip the Bundeswehr with teargas and

pepper spray. Unlike police, however, the Bundeswehr considers teargas

to be a chemical agent. Chemical weapons are internationally banned and

the Bundeswehr is not permitted to use them. In order to equip the

soldiers with teargas or pepper spray, the legislation must first be

changed, including the "law on the implementation of the convention on

chemical weapons". In letters addressed to internal affairs minister

Otto Schily and foreign affairs minister Joschka Fischer, Struck asked

for their "support" so that the Bundeswehr in the future during

international missions "can react adequately beneath the threshold for

the engagement of firearms".

The nationalistic demons in the Balkans may offer KFOR the opportunity

to act again very quickly. Something else can happen again at any

moment, experienced UN policemen fear: after a new incident, at the

next elections but certainly no later than 2005 if the Albanians want

to achieve the independence of the province while the Serbs, with the

support of Belgrade, seek its division into ethnic cantons.

Joerg Lembke, a policeman from Hamburg who is busy in Kosovo on the

identification of bodies from the civil war, does not trust either

UNMIK nor KFOR peacekeeping forces with security. Lembke asked his

colleagues for their correct address and, if possible, a photo of the

house where they live: "So we can prepare a evacuation plan for when we

need to withdraw as fast as possible."

ERP KIM Info-service remarks:

* Fr. Sava was referring to German army, not to Germans in general.

** More about Skenderbey SS division you can find at:

http://www.kosovo.com/skenderbeyss.html

=== DEUTSCH ===

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/decani/message/81752

Die Hasen vom Amselfeld

Renate Flottau, Olaf Ihlau, Alexander Szandar, Andreas Ulrich

DER SPIEGEL

http://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/0,1518,297969,00.html

Schwere Vorwürfe gegen die deutsche Kfor-Schutztruppe in der

Unruheprovinz Kosovo: Deutsche Uno-Polizisten werfen der Bundeswehr

vor, bei den Ausschreitungen albanischer Extremisten gekniffen und

versagt zu haben.

Die Stimme des deutschen Uno-Polizisten überschlug sich vor Panik.

"Wann kommt ihr endlich", schrie der Mann flehentlich in das Funkgerät,

"um Himmels willen, wir brauchen dringend Unterstützung."

Vor dem Gebäude der Uno-Polizei in der Provinzstadt Prizren,

Einsatzsektor der deutschen Kfor-Friedenstruppe in der Unruheprovinz

Kosovo, wütete seit Stunden der entfesselte Mob albanischer

Nationalisten. Er machte Jagd auf Serben und deren vermeintliche

Beschützer. Steine flogen und Molotow-Cocktails, Flammen züngelten auf

hellbrauner Erde neben umgekippten und demolierten Einsatzwagen. Vor

der Orgie des Hasses hatten mehrere Dutzend Uno-Beamte sich in den

Polizeiposten gerettet und verbarrikadiert. Viele bluteten.

"Kommt schnell, wir brauchen Hilfe", hämmerte der deutsche Polizist

wieder und wieder in das Sprechgerät. Doch niemand kam, das Militär

schickte keinerlei Hilfe. Wohl nur der Zufall, dass an diesem zweiten

Tag der März-Ausschreitungen im Kosovo sich in Prizren der Amoklauf der

Albaner dann dem Abfackeln der Kirche Sveti Spas sowie einer Siedlung

zuwandte, in der vor dem Krieg 2000 Serben lebten, mag die

Uno-Mitarbeiter vor dem Schlimmsten bewahrt haben.

Bei dem jüngsten Aufruhr im Kosovo wurden 19 Menschen getötet, 8 Serben

und 11 Albaner. Letztere meist in Notwehr von bedrängten Uno-Polizisten

und Kfor-Soldaten. Nach einer Bilanz der Unmik, der Uno-Zivilverwaltung

dieses internationalen Protektorats, gab es etwa 900 Verletzte,

darunter waren 65 Angehörige der internationalen Kräfte. Es wurden 29

Kirchen und Klöster sowie etwa 800 Häuser der serbischen Minderheit

zerstört, mehrere tausend Serben retteten sich durch Flucht.

Zerstoben sind mit diesen Gewalttaten wohl auch die letzten Illusionen

über eine mögliche Aussöhnung der Volksgruppen und den Aufbau einer

multiethnischen Demokratie. In einem Krieg um Menschenrechte hatten

1999 Nato-Bomber die mörderische Militärmaschinerie des

Serben-Herrschers Slobodan Milosevic aus dem Kosovo vertrieben und 800

000 albanischen Flüchtlingen die Rückkehr ermöglicht. Beklommen muss

die internationale Gemeinschaft fünf Jahre danach erkennen, dass sie

diesen moralischen und militärischen Sieg zu verspielen, ihre

ehrgeizige Mission zu scheitern droht. Viele der Opfer von gestern sind

die Täter von heute. Wie einst der Belgrader Despot, betreiben nun

albanische Extremisten das blutige Geschäft ethnischer Säuberungen, um

den "serbenfreien" Staat "Kosova" zu schaffen - rund um das historische

Amselfeld (Kosovo Polje), auf dem 1389 das serbische Ritterheer im

Kampf gegen die Türken verblutete und den Opfermythos der Serben schuf.

"Wir haben schnell reagiert", beschreibt Generalleutnant Holger

Kammerhoff den Einsatz der 20 500 Mann starken Kfor-Schutztruppe, die

er seit vergangenen Oktober kommandiert, bei den jüngsten Unruhen. Und

auch Verteidigungsminister Peter Struck lobt das "umsichtige Verhalten"

seiner 3600 Soldaten in höchsten Tönen: "Sie haben besonnen reagiert,

eine Eskalation verhindert und so Menschenleben geschützt."

Dies ist die Berliner Version. Berichte von Augenzeugen in Prizren

ergeben indes ein ganz anderes Bild. Nicht nur Serben, sondern auch

Uno-Beamte, Soldaten anderer Truppenkontingente, albanische

Menschenrechtler oder unabhängige Journalisten werfen der Bundeswehr

Versagen, ja Feigheit vor. In der Bekämpfung der Ausschreitungen habe

sie eine klägliche, wenn nicht die blamabelste Rolle gespielt. Die

deutschen Soldaten seien weggerannt, hätten sich wie Hasen in den

Kasernen versteckt und seien mit gepanzerten Fahrzeugen erst wieder

erschienen, als sich der albanische Mob ausgetobt und sein

Vernichtungswerk vollendet hatte. Solch harsche Beschuldigungen hatte

es noch bei keinem der Auslandseinsätze deutscher Militärs gegeben.

In dem Versagen vor dem nackten Terror glaubten einige

Balkan-Beobachter gar einen Hauch von Srebrenica zu verspüren: Als nach

dem Fall der bosnischen Stadt im Juli 1995 der holländische

Uno-Offizier Karremans dem Serben-General Mladic zuprostete, während

Tausende Muslime zur Exekution abtransportiert wurden.

"Ihr Einsatz war ein Fehlschlag, sie sollten abziehen", grollte Bischof

Artemije von der serbischen Diözese Kosovo-Metohija über die Deutschen.

Und Vater Sava Jancic, Sprecher des Klosters Decani, fügte hinzu: "Nach

dem, was die Deutschen in zwei Weltkriegen getan haben, wünschen wir

uns, sie würden vom Balkan verschwinden."

Doch auch die deutschen Uno-Polizisten fühlten sich von den deutschen

Soldaten im Stich gelassen. "Anzeichen von Traumatisierung" hat Herbert

Fischer-Drumm, Polizeipfarrer in Rheinland-Pfalz, bei manchem der 278

deutschen Polizisten in persönlichen Gesprächen registriert, "weil ihre

Hilferufe an die Kfor auf taube Ohren stießen". Viele Beamte, so der

Pfarrer, fragten sich, wozu die Soldaten überhaupt da seien, wenn sie

ihnen nicht Beistand leisten könnten.

Berichte der frustrierten Polizisten liegen unterdessen der

Unmik-Verwaltung vor. Deren finnischer Chef Harri Holkeri, melden

albanische Zeitungen, soll dazu einen vehementen Disput mit dem

Kfor-Kommandeur Kammerhoff geführt haben. Die Berichte werden jetzt

ausgewertet. "Die Kfor muss ihr Sicherheitskonzept überdenken", fordert

Sachsen-Anhalts Innenminister Klaus Jeziorsky (CDU), der vergangene

Woche mit seinem Hamburger Kollegen Udo Nagel von einem Besuch im

Kosovo zurückkehrte. Auch Nagel ist der Ansicht, "Kfor muss in der Lage

sein, die Uno-Mitarbeiter zu schützen".

Nach einer Inspektionsreise am 5. und 6. April fasste der Vorsitzende

der Bund-Länder-Arbeitsgruppe International Police Task Force, der

nordrhein-westfälische Polizeiinspektor Dieter Wehe, die Ergebnisse in

einem Bericht zusammen und schickte sie an das Bundesinnenministerium

sowie die Innenminister der Länder. Wehe kommt zu dem Schluss: "Die

Kfor ist bei gewalttätigen Unruhen zur Lagebewältigung nicht geeignet.

Die Zusammenarbeit zwischen Kfor und Unmik ist nicht abgestimmt."

In Prizren sei "trotz ständiger Hilfeersuchen an die Kfor" kein Militär

erschienen, um die Polizei zu unterstützen. Die Kfor "erwies sich als

unfähig, die ihr übertragenen Aufgaben zu gewährleisten".

Auch Uno-Polizeichef Stefan Feller wird in dem Bericht mit den Worten

zitiert, die Kfor sei den Unruhen nicht gewachsen gewesen, das Militär

nicht ausreichend ausgebildet und vorbereitet. Die Kfor konnte "die ihr

zugewiesenen Objektschutzaufgaben nicht gewährleisten und auch nicht

den Schutz der serbischen Bevölkerung aufrechterhalten".

"Seit Wochen schon wurde die Stimmung immer angespannter", berichten in

Prizren deutsche Polizeibeamte dem SPIEGEL. Sie wollen Namen und

Dienstgrad nicht genannt sehen, weil sie derzeit der Uno unterstellt

sind und jede Aussage rechtliche Folgen hätte.

Der Druck habe sich konkret gegen die noch etwa 100 000 Serben der

Provinz und die Unmik gerichtet, die wegen Kriegsverbrechen auch gegen

die einstige Kosovo-Befreiungsarmee UÇK zu ermitteln begann. Reden

albanischer Nationalisten wurden schärfer, ebenso die politischen

Schmierereien an Häuserwänden. "Es war klar, dass etwas passieren

würde", so ein Beamter, "nur nicht wann." Eruptionen albanischer

Gewalt, bei denen Sprengkommandos systematisch serbische Dörfer,

Klöster und Kirchen attackierten, hatte es seit Kriegsende mehrfach

gegeben. Nur war seinerzeit die Kfor-Schutztruppe mit 50 000 Mann noch

wesentlich agiler. "Man erwartet von uns Wunder", stöhnte schon als

erster Uno-Verwalter der Franzose Bernard Kouchner über die periodisch

wiederkehrenden Ausbrüche des ethnischen Hasses.

Diesmal führte die - unbewiesene - Behauptung, zwei albanische Jungen

seien von Serben in den Fluss Ibar getrieben worden und dort ertrunken,

zur Gewaltexplosion. Zunächst in Kosovska Mitrovica und dann in fast

allen Städten der Krisenprovinz, auch in Prizren.

Dort marschieren, so der Einsatzbericht deutscher Polizisten, am 17.

März etwa tausend Demonstranten durch das Zentrum, skandieren "UÇK -

UÇK" und "Unmik - armik", die Unmik ist der Feind. Menschen aus den

umliegenden Dörfern stoßen hinzu, offenkundig auch Islamisten, an ihren

langen Bärten erkennbar.

Um 17.30 Uhr brennen die ersten Häuser in der Altstadt. Die

Theologische Fakultät der Serben wird unter dem Beifall der Bevölkerung

in Brand gesetzt, Steine fliegen gegen die Zivilverwaltung, Autos

werden demoliert. Von der Kfor ist nichts zu sehen, obwohl besorgte

Augenzeugen mehrmals die deutschen Offiziere telefonisch zum Eingreifen

aufgefordert haben.

Erst als die Flammen auch auf die umliegenden Häuser überzugreifen

drohen, nähern sich Spezialeinheiten der argentinischen Uno-Polizei.

Allerdings nur mit einem Sicherheitsabstand von 300 Metern. Ihr

Versuch, die Menge mit Tränengas aufzulösen, wird mit einem Hagel von

Steinen und Flaschen gekontert. Die Südamerikaner lassen Knüppel und

Schutzschilde fallen und fliehen.

Die deutsche Kfor lässt sich erstmals blicken, als die Randalierer ein

Löschfahrzeug kapern und zum Unmik-Gebäude fahren. Das Erscheinen des

Militärs zeigt offenbar Wirkung. Der Mob zieht weiter, wird an seinem

Vernichtungsmarsch nicht gehindert.

Zwischen 18 und 21 Uhr wütet der Pöbel in der Altstadt am Hang

unterhalb der Ruine einer byzantinischen Burg. Die Häuser serbischer

Flüchtlinge werden angezündet. Ein Zug Kfor-Soldaten, der hinter

Sandsackbarrieren die serbische Kirche St. Georg bewacht, flüchtet mit

Geistlichen und den verbliebenen Serben in eine Kaserne. Die

Demonstranten applaudieren, räuchern die Kirche aus, zünden 56 Häuser

an und schließlich auch, nicht weit vom Bürgermeisteramt, die

griechisch-orthodoxe Kirche Heilige Jungfrau von Ljeviska. Über die

hatte Verteidigungsminister Struck einst gesagt, sie sei ein "Symbol,

dass der Frieden währt und unser Einsatz ihn brachte".

Einige Extremisten ziehen weiter, flussaufwärts an der Bistrica entlang

zum Kloster des Heiligen Erzengels Michael. Der Zufahrtsweg wäre mit

ein paar Panzern zu blockieren, zumal an dem Bauwerk aus dem 14.

Jahrhundert die Bundeswehr stationiert ist - Hauptfeldwebel Udo Wambach

mit 19 Soldaten.

Die etwa 200 Demonstranten schicken eine Delegation mit weißer Fahne zu

den Deutschen und versichern, ihnen werde kein Leid geschehen, "wir

wollen nur das Kloster abfackeln". Die Kfor-Beschützer setzen sechs

Mönche und zwei Besucher in ihre gepanzerten Fahrzeuge und fahren durch

das Niedrigwasser der Bistrica davon. Das Kloster wird niedergebrannt.

Hauptfeldwebel Wambach wird für seine "hervorragende Einzeltat" Mitte

April bei einem Prizren-Besuch von Verteidigungsstaatssekretär Walter

Kolbow ausdrücklich belobigt. Kein Orden, aber immerhin ein Vermerk in

der Personalakte. Der Feldwebel habe, so die Würdigung, "durch

umsichtiges Verhalten, mutiges Verhandeln eine Eskalation der Gewalt

vermieden, Blutvergießen verhindert und die ihm anvertrauten

Menschenleben geschützt".

Als die Nacht einbricht, erhellt der Feuerschein der brennenden

Altstadt den Himmel über Prizren. Am nächsten Morgen, Donnerstag, 18.

März, rauchen die Trümmer noch immer. Aber es bleibt zunächst ruhig.

Gegen 12.30 Uhr tritt der Pöbel erneut in Aktion. Da sämtliche

serbischen Einrichtungen zerstört sind, richtet sich der Hass der

Albaner nun gegen die Stadtverwaltung, die Uno-Zivilverwaltung und die

beiden Polizeistationen.

Die erste Attacke trifft gegen 15 Uhr die Polizeiwache in der

Innenstadt. Hilferufe an die Kfor bleiben erfolglos. Steine fliegen

gegen das Haus, Autos werden umgeworfen, von Soldaten ist nichts zu

sehen. Die Kfor hatte die Zeit offenkundig nicht genutzt, das

Einsatzkonzept zu überdenken, um erneuten Unruhen zu begegnen.

Dann der Angriff auf das einen Kilometer weiter gelegene

Polizeihauptquartier. Polizisten aus verschiedenen Nationen, auch

deutsche, sind einem Dauerfeuer aus Steinen und Molotow-Cocktails

ausgesetzt, von der nahen Tankstelle kriegen die Extremisten immer

wieder Nachschub. Schüsse fallen.

"Wir haben die Kfor um Hilfe angefleht", berichtet ein Beamter. Die

Soldaten kämen gleich, heißt es. Doch nichts geschieht. Das Einzige,

was die Polizisten sehen, ist ein Militärauto, in dem Soldaten von

einem nahen Hügel aus die Gewaltorgie beobachten. "Ich kam mir vor wie

der letzte Dreck", schreibt ein deutscher Polizist in seinem Rapport.

"Das Schlimmste" sei, so ein anderer Beamter, dass die Randalierer ihre

Ziele erreicht hätten: Die Soldaten schauten zu, als die ethnische

Säuberung ein Stück weiter vorangetrieben wurde, "unsere Mission ist

gescheitert".

Erst als die Randalierer von Prizren in den Hof des Unmik-Gebäudes

Granaten werfen, greift die deutsche Kfor-Truppe ein. Sie schickt

gepanzerte Fahrzeuge, und die Situation beruhigt sich sofort.

Das deutsche Kontingent in Prizren hatte während des zweitägigen Chaos

keine Verletzten zu beklagen. Das ist schön. Aus anderen

Kfor-Kontingenten wurden zahlreiche Verletzte gemeldet, zum Beispiel

bei den Italienern, Griechen, Franzosen. Hatten diese Kfor-Soldaten

nicht dieselben Direktiven wie die Deutschen? Handelten sie auf eigene

Faust, oder waren sie schlicht mutiger?

14 Verwundete gab es beim schwedischen Bataillon, das versuchte, das

Serben-Dorf -aglavica vor den albanischen Feuerteufeln zu schützen.

"Wir waren überrascht und warten jetzt auf die nächste Runde",

vertraute Unteroffizier Andersson Reportern an, "wir werden das diesen

Albanern heimzahlen." In Mitrovica, wo es die meisten Toten gab,

verhinderten französische Kfor-Soldaten und Uno-Polizei, dass die

Albaner in den serbischen Nordteil der Stadt gelangen konnten.

Warum es denn nicht möglich war, die Klöster zu schützen, werden in

Prizren deutsche Offiziere von einem Journalisten des kanadischen

"Chronicle Herald" gefragt. Ihre Antwort: "Es ist nicht unser Mandat,

unschuldige Zivilisten zu verletzen, um eine alte Kirche zu schützen."

Auf ähnlicher Linie wehrt sich Oberst Dieter Hintelmann, der Führer des

deutschen Kfor-Kontingents in Prizren: "Wir haben genau nach unseren

Bestimmungen gehandelt."

Objektschutz ist nicht die Aufgabe der Bundeswehr im Kosovo. Geschossen

werden darf nur in Notwehr.

Jeder Soldat hat eine kleine "Taschenkarte" mit den "Rules of

Engagement", den Einsatzvorschriften, dabei. Gebäude mit Waffengewalt

zu schützen und auf Demonstranten zu schießen, die MolotowCocktails in

Kirchen oder Klöster schleudern, ist darin nicht vorgesehen. Das

Kapitel "Regeln für die Anwendung militärischer Gewalt" macht den

Soldaten eindeutige Vorgaben: "Sie haben das Recht, Angriffe

abzuwehren, die sich gegen Kfor-Personal, Kfor-Material und unter

Schutz von Kfor stehende Personen richten." Doch von diesem Recht,

schimpfen deutsche Polizisten, machte die Bundeswehr in Prizren leider

keinen Gebrauch.

"Die Anführer der Demonstrationen wussten genau, solange sie uns nicht

angreifen, können wir nicht schießen", sagt Hintelmann. Also ein

Freibrief für den rasenden Pöbel? "Ich kann doch nicht auf eine

Menschenmenge schießen lassen, in der sich auch Kinder befanden",

erklärt der Offizier. Demonstrationszüge, in denen auch Frauen und

Kinder waren, hätten das Feldlager blockiert und so das Ausrücken von

Verstärkung verhindert.

Massive Rückendeckung erhält der Offizier von Vorgesetzten in der

Heimat.

"Kern unserer Aufgabe ist es, Menschenleben zu schützen", so das

Einsatzführungskommando in Potsdam, Hintelmanns vorgesetzte

militärische Dienststelle. Zu Recht habe sich die Truppe "darauf

konzentriert, serbische Bevölkerung und Uno-Mitarbeiter zu schützen".

Darauf allerdings warteten die deutschen Polizisten vergebens.

Vorwürfe, die Deutschen hätten feige gekniffen, sind auch für den

Bundeswehrchef "völlig absurd". Nach den geltenden deutschen Gesetzen

dürften die Soldaten weder Tränengas einsetzen noch mit Gummigeschossen

in eine Menschenmenge schießen, sondern, erläutert Struck, nur

"Warnschüsse in die Luft abgeben".

Auch der Außenminister ("Ich gehöre nicht zu denen, die Vorwürfe gegen

die Soldaten erheben") nimmt die Truppe in Schutz. "Unsere Soldaten

haben unter erheblichem Risiko und unter enormem Druck Großes

geleistet", so der Grüne Joschka Fischer, "sie haben viele Menschen

gerettet, diese Priorität war richtig."

Eines hingegen räumen die Deutschen in Prizren wie in Berlin

mittlerweile ein: Sie wurden von dem Aufstand, der sich binnen Stunden

zum Flächenbrand ausweitete, völlig überrascht. Die Kfor-Aufklärung und

diverse nationale Geheimdienste hatten versagt.

Dabei hatten sich gerade die Deutschen gerühmt, ihre Kontakte zur

Bevölkerung seien hervorragend, wobei ihnen auch ein historischer Bonus

zugute kam: Im Zweiten Weltkrieg unterstützten Albaner die Wehrmacht im

Kampf gegen serbische Partisanen und schickten Hitler sogar eine

SS-Division, benannt nach ihrem Nationalhelden Skanderbeg.

Wer im Kosovo "künftig einen Angriff auf serbische Enklaven oder

Kulturgüter startet, wird auf die Kfor stoßen", kündigte

Generalleutnant Kammerhoff unterdessen eine härtere Gangart an, damit

implizit ein Fehlverhalten einräumend. Von einem "Handlungsbedarf für

die Aufgabe riot-control" spricht ein interner "Sachstandsbericht" der

Truppe.

Minister Struck möchte die Bundeswehr nun mit Tränengas und

Pfefferspray ausrüsten. Anders als bei der Polizei gilt Tränengas für

das deutsche Militär als chemischer Kampfstoff. Chemiewaffen aber sind

international geächtet, ihre Anwendung ist der Bundeswehr nicht

erlaubt. Um die Soldaten mit Tränengas oder Pfefferspray auszurüsten,

müssen erst Rechtsvorschriften geändert werden, darunter das

"Ausführungsgesetz zum Chemiewaffenübereinkommen". In Briefen an

Innenminister Otto Schily und Außenminister Joschka Fischer bat Struck

um "Unterstützung", damit die Bundeswehr künftig bei Auslandseinsätzen

"unterhalb der Schwelle des Schusswaffeneinsatzes angemessen reagieren"

könne.

Die nationalistischen Dämonen auf dem Balkan dürften der Kfor schon

sehr bald erneut Gelegenheit zum Handeln bieten. Es könne jederzeit

wieder losgehen, fürchten erfahrene Uno-Polizisten: Nach irgendeinem

neuen Zwischenfall, bei den nächsten Wahlen, spätestens aber 2005, wenn

die Albaner die Unabhängigkeit der Provinz durchpauken wollen und die

Serben, von Belgrad gestützt, eine Aufteilung in ethnische Kantone

(siehe Kostunica-Interview Seite 146).

Jörg Lembke, Polizist aus Hamburg und im Kosovo mit der Identifizierung

von Leichen aus dem Bürgerkrieg beschäftigt, traut jedenfalls in Sachen

Sicherheit weder der Unmik noch der Kfor-Schutztruppe. Seine Kollegen

hat Lembke aufgefordert, ihre exakte Anschrift, möglichst mit einem

Foto ihres Hauses abzugeben: "Dann können wir einen Evakuierungsplan

ausarbeiten, damit wir möglichst schnell rauskommen."

=== SRPSKOHRVATSKI ===

http://www.apisgroup.org/article.html?id=1859

Der Spiegel, Nemacka

3 maj, 2004

Kukavicluk nemackih vojnika

ZECEVI SA KOSOVA

Ozbiljni prekori upuceni nemackim snagama KFOR-a u nemirnoj pokrajini

Kosovo: Nemacki UN policajci optuzuju Nemacku vojsku (Bundeswehr) da su

ponizeni i porazeni u nasilju albanskih ekstremista

Renate Flottau, Olaf Ihlau, Aleksander Szandar, Andreas Ulrich

Hamburg, 3. maja - Glas nemackog policajca UN odavao je paniku. "Kad

cete vec jednom doci", molio je covek preko radio-veze, "za boga

miloga, hitno nam je potrebna podrska".

Ispred zgrade policije UN u Prizrenu, sektoru nemackih snaga Kfora na

Kosovu, razularena masa albanskih nacionalista je satima pravila nered.

Oni su krenuli u lov na Srbe i njihove navodne zastitnike. Letele su

kamenice i molotovljevi kokteli, plamen je prekrio svetlo braon zemlju

pored prevrnutih i demoliranih vozila. Pred takvom orgijom mrznje vise

desetina sluzbenika UN se sklonilo u zgradu policije gde se

zabarikadiralo. Mnogi su krvarili.

"Dodjite brzo, potebna nam je pomoc", ponovio je nemacki policajac vise

puta preko radio-veze. Ali, niko nije dosao, vojska nije poslala pomoc.

Saradnike UN je od najgoreg spasila slucajnost to sto se drugog dana

martovskih nemira na Kosovu ludilo Albanaca u Prizrenu okrenulo ka

paljenju crkve Svetog spasa i naselju u kojem je pre rata zivelo 2.000

Srba.

Prilikom nedavne pobune na Kosovu ubijeno je 19 ljudi, osam Srba i 11

Albanaca koje su uglavnom ubili ugrozeni policajci UN i vojnici Kfora u

samoodbrani. Prema bilansu Unmika, civilne uprave UN ovog medjunarodnog

protektorata, bilo je oko 900 povre- djenih, medju kojima 65 pripadnika

medjunarodnih snaga. Unisteno je 29 crkava i manastira kao i oko 800

kuca pripadnika srpske manjine, dok je vise hiljada Srba pobeglo i tako

se spasilo.

Ovim nasiljem srusene su i poslednje iluzije o mogucem pomirenju

nacionalnih zajednica i izgradnji multietnicke demokratije. U ratu za

ljudska prava NATO bombarderi su 1999. godine proterali ubilacku vojnu

masineriju srpskog despota Slobodana Milosevica sa Kosova i omogucili

povratak 800.000 albanskih izbeglica. Medjunarodna zajednica sada posle

pet godina mora da prizna da je proigrala ovu moralnu i vojnu pobedu,

njena ambiciozna misija preti da propadne. Mnoge tadasnje zrtve su

danasnji zlocinci. Kao nekad beogradski despot sada albanski

ekstremisti vrse krvavo etnicko ciscenje da bi stvorili drzavu Kosovo

bez Srba - oko istorijskog Kosova Polja na kojem su srpski vitezovi

1389. godine krvarili u borbi protiv Turaka i stvorili mit o Srbima kao

zrtvama.

"Mi smo brzo reagovali", opisuje general-potpukovnik Holger Kamerhof

angazovanje 20.500 ljudi u sastavu Kfora kojima on komanduje od oktobra

prosle godine. I nemacki ministar odbrane Peter Struk hvali "oprezno

ponasanje" svojih 3.600 vojnika: "Oni su reagovali razumno, sprecili su

eskalaciju i tako zastitili ljudske zivote".

Ovo je verzija Berlina. Izjave ocevidaca u Prizrenu, medjutim, na kraju

odaju drugaciju sliku. Ne samo Srbi, vec i sluzbenici UN, vojnici

drugih kontingenata, albanski borci za ljudska prava ili nezavisni

novinari prebacuju Bundesveru da je zakazao pa cak i da se poneo

kukavicki. U suzbijanju nemira Bundesver je odigrao jednu zalosnu, ako

ne i najsramotniju ulogu. Nemacki vojnici su pobegli, sklonili se poput

zeceva u kasarnu i ponovo izasli sa oklopnim vozilima tek kada se

albanska rulja smirila i zavrsila svoj rusilacki posao. Do sada se nije

mogla cuti ovako teska optuzba na racun nemacke vojske u nekoj drugoj

misiji u inostranstvu.

Neuspeh da se spreci ovaj teror mnoge balkanske posmatrace podseca na

Srebrenicu: kada je nakon pada ovog bosanskog grada u julu 1995. godine

holandski oficir UN Karemans nazdravio srpskom generalu Mladicu dok su

hiljade muslimana odvodjene na egzekuciju.

"Njihova intervencija bila je neuspesna, oni bi trebalo da se povuku",

rekao je vladika rasko-prizrenski Artemije o Nemcima. A otac Sava

Janjic, portparol manastira Decani, dodao je: "Nakon onoga sto su Nemci

ucinili u dva svetska rata, mi zelimo da oni odu sa Balkana".

Medjutim, i nemacki policajci UN su osecali da su ih nemacki vojnici

ostavili na cedilu. "Znake traumatizacije", primetio je Herbert

Fiser-Drum, pastor pri policiji u Rajnsko-falackoj oblasti, kod nekih

od 278 nemackih policajaca sa kojima je licno razgovarao, "zato sto

njihovi pozivi u pomoc upuceni Kforu nisu naisli na prijem". Mnogi

sluzbenici, kaze ovaj svestenik, pitali su se zasto su vojnici uopste

bili tu kada nisu mogli da im pruze podrsku.

Svedocenja razocaranih policajaca predocena su, medjutim, upravi

Unmika. Njihov sef Hari Holkeri, izvestavaju albanske novine, navodno

je imao zestoku raspravu sa komandantom Kfora Kamerkofom. Izvestaji se

sada proveravaju. "Kfor mora da preispita svoj koncept bezbednosti",

zahteva ministar unutrasnjih poslova pokrajine Saksonija Anhalt - Klaus

Jeciorski, koji se prosle nedelje vratio sa svojim hamburskim kolegom

Udom Nagelom iz posete Kosovu. I Nagel je misljenja da "Kfor mora da

bude u stanju da zastiti saradnike UN."

Nakon posete Kosovu 5. i 6. aprila predsedavajuci nemacke radne grupe

za medjunarodne policijske snage policijski inspektor Severne Rajne i

Vestfalije Diter Ve, sazeo je rezultate svoje provere u izvestaj i

poslao ga saveznom ministarstvu unutrasnjih poslova kao i ppokrajinskim

ministrima unutrasnjih poslova. On je dosao do zakljucka: "U nasilnim

nemirima Kfor nije prigodan za smirivanje situacije. Saradnja izmedju

Kfora i Unmika nije uskladjena".

U Prizrenu se "uprkos stalnim pozivima u pomoc upucenim Kforu" nije

pojavio nijedan vojnik da zastiti policiju. Kfor "se pokazao

nesposobnim da obavlja zadatke koji su mu dodeljeni".

U izvestaju se navode i reci sefa policije UN Stefan Feler da Kfor nije

dorastao smirivanju nemira, da vojska nije dovoljno obucena i

pripremljena. Kfor nije mogao da garantuje "zadatke zastite objekata

koji su mu dodeljeni i da pruzi zastitu srpskom narodu".

"Vec nedeljama se osecala sve napetija atmosfera", kazu nemacki

policijski sluzbenici u Prizrenu. Oni nisu zeleli da se navedu njihova

imena i cinovi jer su sada pod komandom UN i svaki iskaz povlaci pravnu

posledicu.

Pritisak se konkretno usmerio na nekih 100.000 Srba u pokrajini i na

Unmik koji je zbog ratnih zlocina poceo da vodi istragu protiv

nekadasnje Oslobodilacke vojske Kosova. Retorika albanskih nacionalista

je postojala ostrija, bas kao i politicke poruke na zidovima kuca.

"Bilo je jasno da ce se nesto dogoditi", rekao je jedan sluzbenik,

"samo se nije znalo kad". Erupcija albanskog nasilja prilikom cega su

se sistematski napadala srpska sela, manastiri i crkve bilo je u vise

navrata od kraja rata. Samo sto su svojevremeno zastitne snage Kfora sa

50.000 vojnika bile znatno agilnije. "Od nas se ocekuje cudo", jadao se

je jos prvi administrator UN Francuz Bernar Kusner povodom izliva

medjunacionalne mrznje koji su se periodicno ponavljali.

Ovog puta je - nepotvrdjena - tvrdnja da su Srbi naterali dva albanska

decaka da skoce u Ibar u kome su se udavili, dovela do eksplozije

nasilja. Najpre u Kosovskoj Mitrovici, a onda u gotovo svim gradovima

ove krizne pokrajine, pa i u Prizrenu.

Tamo, prema pricanju nemackih policajaca, 17. marta marsira oko hiljadu

demonstranata kroz centar grada skandirajuci "OVK - OVK" i "Unmik -

armik", Unmik je neprijatelj. Ljudi iz obliznjih sela su se

prikljucivali, ocigledno da su bili islamisti jer su imali duge brade.

U 17.30 sati pocinju da gore prve kuce u starom gradu. Srpska

Bogoslovija je zapaljena uz odobravanje okupljenih stanovnika, kamenice

su bacane na civilnu administraciju, automobili su demolirani. Od Kfora

ni traga, mada su zabrinuti ocevici vise puta telefonom trazili od

nemackih oficira da intervenisu.

Tek kada je vatra pretila da zahvati okolne kuce priblizavaju se

specijalne jedinice argentinske policije UN. Doduse, ostaju na

bezbednom odstojanju od 300 metara. Njihov pokusaj da rasteraju gomilu

pomocu suzavca izazvao je bacanje kamenica i flasa. Juznoamerikanci su

bacili palice i zastitne oklope i pobegli.

Nemacki Kfor se mogao videti tek kada su nasilnici uzeli vatrogasno

vozilo i dovezli se do zgrade Unmika. Pojava vojske ocigledno je imala

efekta. Masa nastavlja, nista je ne sprecava u njenom rusilac kom marsu.

Izmedju 18 i 21 cas masa pravi nerede u starom gradu na obronku ispod

ostataka vizantijske tvrdjave. Kuce srpskih izbeglica su zapaljene.

Jedna ceta vojnika Kfora, koja iza barikada od dzakova peska stiti

srpsku crkvu Svetog Georgija, bezi sa duhovnicima i preostalim Srbima u

jednu kasarnu. Demonstranti aplaudiraju, pale crkvu i jos 56 kuca i

konacno, nedaleko od opstine, pravoslavni Hram bogorodice Ljeviske. O

njoj je nemacki ministar odbrane Struk svojevremeno rekao da

predstavlja "simbol ocuvanja mira koji je donela nasa misija".

Neki ekstremisti nastavljaju dalje uzvodno duz Bistrice do manastira

Svetih arhangela. Put do tamo se mogao blokirati sa nekoliko oklopnih

vozila pogotovo sto je u toj gradjevini iz 14. veka stacioniran

Bundesver - narednik Udo Vambah sa 19 vojnika.

Oko 200 demonstranata salje delegaciju sa belom zastavicom kod Nemaca i

uverava ih da im se nece desiti nista lose, "mi zelimo samo da zapalimo

manastir". Zastitnici iz redova Kfora sklanjaju sest monaha i dva

posmatraca u svoja oklopna vozila i odvoze ih preko Bistrice. Manastir

je spaljen.

Narednika Vambaha je za njegovo "istaknuto delo" sredinom aprila

izricito pohvalio zamenik ministra odbrane Valter Kolbov prilikom

posete Prizrenu. Nema ordena, ali beleska ulazi u dosije. On je, kako

glasi ocena, "opreznim ponasanjem i odvaznim delovanjem izbegao

eskalaciju nasilja, sprecio krvoprolice i zastitio ljudske zivote koji

su mu povereni".

Kada se spustila noc vatra iz starog grada je obasjavala nebo iznad

Prizrena. Sledeceg jutra u cetvrtak 18. marta iz rusevina se jos uvek

vije dim. Ali za sada je sve mirno.

Oko 12.30 masa ponovo stupa akciju. Unistene su sve srpske ustanove,

mrznja Albanaca se sada usmerava na gradsku upravu, civilnu

administraciju UN i dve policijske stanice.

Prvi napadi pocinju oko 15 casova i pogadjaju policijsku strazu u

centru grada. Pozivi u pomoc upuceni Kforu ostaju bez uspeha. Kamenice

lete na kuce, prevrcu se automobili, a vojnici se ne mogu nigde videti.

Kfor ocigledno nije iskoristio ovo vreme da preispita svoj koncept

angazovanja kako bi sprecio nove nemire.

Zatim sledi napad na glavni policijski stab udaljen kilometar odatle.

Policajci iz razlicitih drzava, medju njima i Nemci, izlozeni su

konstantnim napadima kamenica i molotovljevih koktela. Iz obliznje

pumpe ekstremisti dobijaju podrsku. Puca se.

"Mi smo molili Kfor za pomoc" kaze jedan sluzbenik. Rekli su nam da

vojnici stizu odmah. Ali, nista se ne desava. Jedino sto policajci vide

jeste vojni automobil u kojem vojnici sa obliznjeg brezuljka posmatraju

orgijanje nasilja. "Osetio sam se kao poslednji bednik", pise nemacki

policajac u svom izvestaju. "Najgore je", kaze jedan drugi sluzbenik,

sto su izgrednici postigli svoje ciljeve: vojnici su posmatrali kako je

etnicko ciscenje otislo korak dalje, "nasa misija je propala".

Tek kada su nasilnici u Prizrenu bacili granate u dvoriste zgrade

Unmika nemacki Kfor se umesao. Poslao je oklopna vozila i situacija se

odmah smirila.

Nemacki kontingent u Prizrenu nije tokom dvodnevnog haosa prijavio da

je imao povredjene. To je bas lepo. Drugi kontingenti Kfora su

prijavili veci broj povre- djenih, na primer Italijani, Grci, Francuzi.

Zar ovi vojnici Kfora nisu imali iste direktive kao i Nemci? Da li su

oni radili na svoju ruku ili su jednostavno bili odvazniji?

U svedskom bataljonu koji je pokusao da zastiti Srbe u selu Caglavica

od albanskih vatrenih djavola bilo je 14 povredjenih. "Mi smo bili

iznenadjeni i sada cekamo sledecu rundu", priznao je podoficir Anderson

reporterima, "mi cemo se osvetiti ovim Albancima". U Mitrovici, gde je

bilo najvise mrtvih, francuski vojnici Kfora i policija UN su sprecili

da Albanci stignu u severni deo grada. Zasto nije bilo moguce zastititi

manastir pitao je nemacke oficire jedan novinar kanadskog lista

"Hronikl herald". Njihov odgovor: mi nemamo mandat da povredjujemo

neduzne civile da bismo zastitili jednu staru crkvu".

Sa slicnim recima brani se pukovnik Diter Hintelman, komandant nemackog

kontingenta Kfora u Prizrenu: "Mi smo postupali tacno po nasim

propisima".

Zastita objekata nije zadatak Bundesvera na Kosovu. On sme da puca samo

u samoodbrani.

Svaki vojnik ima kod sebe mali "dzepni spisak" sa "pravilima

postupanja". Tu nije predvidjeno da se zgrade stite uz upotrebu oruzja

i pucanje na demonstrante koji bacaju molotovljeve koktele na crkve ili

manastire. Poglavlje "pravila za upotrebu vojne sile" daje vojnicima

jasne preporuke: "Imate pravo da se branite od napada koji su usmereni

na osoblje Kfora, materijal Kfora i osobe koje se nalazi pod zastitom

Kfora". Medjutim, ovo pravo, kritikuju namacki policajci, Bundesver u

Prizrenu na zalost nije iskoristio.

"Predvodnici demonstracija su tacno znali da mi ne mozemo da pucamo ako

nas ne napadnu", kaze Hintelman. Dakle, povlastica za pobesnelu masu?

"Ja ne mogu da naredim da se puca u gomilu ljudi u kojoj se nalaze i

deca", kaze oficir. Kolone demonstranata u kojima su bile i zene i deca

blokirali su poljski logor i tako sprecili pojacanje. Snaznu podrsku

oficir dobija od pretpostavljenih u domovini.

"Sustina naseg zadatka je da zastitimo ljudske zivote", kaze komanda za

rukovodjenje misije u Potsdamu gde se nalaze Hintelmanovi vojni

pretpostavljeni. S pravom su se snage "koncentrisale na to da zastite

srpsko stanovnistvo i saradnike UN". Doduse, na to su cekali i nemacki

policajci uzaludno.

Optuzbe da su se Nemci kukavicki povukli za sefa Bundesvera su "potpuno

apsurdni". Prema vazecim nemackim zakonima vojnici ne smeju da upotrebe

suzavac niti da pucaju gumenim mecima u gomilu ljudi vec, kako obja-

snjava Struk, samo da "ispale pucnje upozorenja u vazduh".

I ministar inostranih poslova ("Ja ne pripadam onima koji optuzuju

vojnike") uzima trupe u zastitu. "Nasi vojnici su ucinili puno toga uz

ogroman rizik i pod enormnim pritiskom", rekao je Joska Fiser, "oni su

spasili puno ljudi i ovaj prioritet je bio ispravan". Nasuprot tome,

jednu stvar priznaju i Nemci u Prizrenu i oni u Berlinu: svi su bili

potpuno izena- djeni pobunom koja se za samo par casova prosirila na

celu pokrajinu. Izvidjacke jedinice Kfora i tajne sluzbe raznih drzava

su zakazale.

Pri tome su se bas Nemci hvalili da su njihovi kontakti sa stanovni-

stvom bili izuzetni pri cemu im je koristio i svojevrsni istorijski

bonus: u Drugom svetskom ratu Albanci su podrzalli Vermaht u borbi

protiv srpskih partizana i cak su poslali Hitleru jednu SS diviziju

nazvanu po njihovom nacionalnom heroju Skenderbegu.

Svako ko "ubuduce napadne srpske enklave ili kulturna dobra na Kosovu

suocice se sa Kforom", najavio je general-potpukovnik Kamerhof zescu

reakciju priznaju- ci tako implicitno pogresno pona- sanje. "O potrebi

delovanja da bi se nemiri stavili pod kontrolu" govori jedan interni

izvestaj trupa.

Ministar Struk bi sada zeleo da opremi Bundesver suzavcem i drugim

slicnim hemikalijama. Za razliku od policije suzavac za nemacku vojsku

predstavlja i hemijski borbeni materijal. Hemijsko oruzje je, medjutim,

medjunarodno zabranjeno, njegova upotreba nije dozvoljena Bundesveru.

Da bi opremio vojnike suzavcem i slicnim hemikalijama prvo moraju da se

izmene pravni propisi, medju kojima i "zakon o primeni sporazuma o

hemijskom oruzju". U pismima upucenim ministru unutrasnjih poslova Otu

Siliju i ministru inostranih poslova Joski Fiseru, Struk je zamolio za

"podrsku" kako bi Bundesver ubuduce prilikom misija u inostranstvu

mogao "da reaguje adekvatno "ispod praga upotrebe vatrenog oruzja".

Nacionalistickim demonima na Balkanu Kfor bi vrlo brzo mogao ponovo da

pruzi priliku da deluju. U svakom trenutku ponovo bi moglo da desi

nesto, strahuju iskusni policajci UN: nakon nekog novog incidenta, na

sledecim izborima, ali najkasnije 2005, ako Albanci zele da ostvare

nezavisnost pokrajine, a Srbi uz podrsku Beograda podelu na etnicke

kantone.

Jerg Lembke, policajac iz Hamburga koji se na Kosovu bavi

identifikovanjem leseva iz gradjanskog rata ne veruje po pitanju

bezbednosti ni Unmiku, a ni zastitnim snagama Kfora. Lembke je od

svojih kolega trazio njihove tacne adrese, eventualno sa fotografijom

kuce: "Onda mozemo da razradimo plan evakuacije kako bismo sto pre

mogli da se povucemo."

[ Il settimanale tedesco DER SPIEGEL, in un recente articolo dai toni

allarmati sulla esplosione dei pogrom lo scorso marzo e sul perdurare

delle violenze degli irredentisti pan-albanesi, definisce semplicemente

"conigli" i soldati tedeschi dell'UNMIK apparentemente incapaci di

difendere le persone ed il patrimonio storico-artistico della

provincia... ]

THE RABBITS OF KOSOVO

DIE HASEN VOM AMSELFELD

ZECEVI SA KOSOVA

(R. Flottau, O. Ihlau, A. Szandar, & A. Ulrich - DER SPIEGEL)

=== ENGLISH ===

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/decani/message/81752

Der Spiegel, Germany

May 3, 2004

German soldiers: The Rabbits of Kosovo*

*In German Original: Amsfeld - Field of blackbirds (in Serbian - Kosovo

Polje)

Serious criticism of the German KFOR contingent in the restless

province of Kosovo: German UN policemen accuse the Bundeswehr (German

Army) of humiliation and defeat during violence by Albanian extremists.

By Renate Flottau, Olaf Ihlau, Alexander Szandar, Andreas Ulrich

The voice of the German UN policeman betrayed panic. "When will you

finally came," pleaded the man over the radio, "For God's sake, we

urgently need support."

In front of the building of the UN police in the town of Prizren, in

the sector of the German KFOR peacekeeping force in the restless

province Kosovo, the unbridled mass of Albanian nationalists raged for

hours. They set out on a hunt for Serbs and their alleged protectors.

Stones flew and Molotov cocktails, flames covered the light brown earth

next to the turned over and destroyed police cars. Confronted with this

orgy of hate, several dozen UN officials had sought sanctuary in the

police station and barricaded themselves. Many were bleeding.

"Come quickly, we need assistance," repeated the German policeman again

and again over the radio. But nobody came and the military sent no

assistance. The UN employees were probably saved from the worst only by

the circumstance that on the second day of the March riots, the madness

of the Albanians turned toward the burning of the church of Sveti Spas

(Christ the Savior) and the settlement where 2,000 Serbs had lived

before the war.

During the recent riots in Kosovo 19 people were killed, 8 Serbs and 11

Albanians, the latter primarily in self-defense by threatened UN

policemen and KFOR soldiers. According to the balance sheet of UNMIK,

the UN civil administration of this international protectorate, there

were about 900 injured, among them 65 members of the international

forces. Twenty-nine churches and monasteries, as well as about 800

houses belonging to the Serbian minority were destroyed, while several

thousand Serbs saved themselves by fleeing.

With these acts of violence probably the last illusions of a possible

reconciliation of the national communities and the building of a

multiethnic democracy have been destroyed. In the war for human rights

in 1999 NATO bombers expelled the murderous military machinery of

Serbian ruler Slobodan Milosevic from Kosovo and enabled the return of

800,000 Albanian refugees. Five years later the international community

must recognize that it has gambled away its moral and military victory

and that its ambitious mission is in danger of failing. Many of the

victims of yesterday are the criminals of today. Like the former

Belgrade despot, Albanian extremists are now carrying out bloody ethnic

cleaning in order to create a Serb-free state of Kosovo - centering on

the historic Field of Blackbirds (Kosovo Polje) where an army of

Serbian knights bled in the battle against the Turks in 1389 and

created the myth of the Serbs as victims.

"We reacted quickly," lieutenant general Kammerhoff said of the

engagement of the 20,500 KFOR troops, which he has commanded since last

October. German defense minister Peter Struck also highly praised the

"prudent behavior" of his 3,600 soldiers: "They reacted rationally,

preventing an escalation and thus protecting human lives."

That is Berlin's version. Reports of eyewitnesses in Prizren, however,

reveal a completely different picture. Not only Serbs, but also UN

officials, troops from other KFOR contingents, Albanian human rights

activists and independent journalists accuse the Bundeswehr of failure

and even cowardice. The Bundeswehr played a sad, perhaps even very

shameful role in restraining the violence. The German soldiers ran

away, hiding like rabbits in their barracks and emerged again with

armored vehicles only once the Albanian crowd had calmed down, having

completed its work of destruction. So far no other such harsh

accusation has been heard against the international missions of the

German military.

The failure to stop this naked terror reminded some Balkans observers

of Srebrenica: After the fall of the Bosnian city in July 1995, the

Dutch UN officer Karremans was toasting the Serb general Mladic while

thousands of Muslims were removed for execution.

"Their intervention was a failure, they should withdraw," said Bishop

Artemije of the Serbian Diocese of Kosovo and Metohija, speaking of the

Germans. And Father Sava Janjic, the spokesman for Decani monastery,

added: "After what the Germans have done in two world wars, we want

them to leave the Balkans."(*)

But the German UN policemen, too, felt abandoned by the German

soldiers. Herbert Fischer Drumm, the police pastor in

Rhineland-Palatinate, discovered "signs of trauma" in some of the 278

German policemen with whom he personally spoke, "because their calls

for assistance to KFOR fell on deaf ears". Many officials, the minister

said, ask themselves why the soldiers were there in the first place if

they could not offer them assistance.

Reports of the frustrated policemen have been presented, in the

meanwhile, to UNMIK. Their Finnish boss Harri Holkeri, Albanian

newspapers report, allegedly had a bitter dispute with the KFOR

commander Kammerhoff. The reports are now being evaluated. "KFOR must

reexamine its concept of security," demanded Saxonia-Anhalt interior

affairs minister Klaus Jeziorsky (CDU), who returned last week with his

colleague from Hamburg Udo Nagel from a visit to Kosovo. Nagel is also

of the opinion that "KFOR must able be to protect UN employees".

After an inspection tour of Kosovo on 5 and 6 April, the chairman of

the German task group for international police forces, North

Rhine/Westphalia police inspector Dieter Ve, summarized the results of

his findings in a report and sent it to the German interior ministry

and provincial interior ministers. His conclusion: "During violent

unrest KFOR is not adapted to calming the situation. Cooperation

between Kfor and Unmik is not coordinated."

In Prizren "despite constant requests for assistance to KFOR" not one

soldier appeared in order to support the police. KFOR "proved to be

unable to carry out its assigned tasks".

UN police commissioner Stefan Feller is also quoted in the report as

saying that KFOR is not up to calming of riots, that the military not

sufficiently trained and prepared. KFOR could not guarantee "security

tasks assigned to it and provide protection for the Serbian population".

"For weeks a steady increase in tension could be felt," German police

officers in Prizren told Der Spiegel. They do not want to give their

names and rank because they are presently under UN command and any

statement could have legal consequences.

The pressure was concretely directed against the some 100,000 Serbs

remaining in the province and against UNMIK, which has began to conduct

an investigation against the former Kosovo Liberation Army for war

crimes. The rhetoric of the Albanian nationalists became more sharp, as

did the political graffiti written on the walls. "It was clear that

something was going to happen," said one official, "we just didn't know

when." Eruptions of Albanian violence during which Serbian villages,

monasteries and churches were systematically attacked have occurred on

several occasions since the end of the war. However, earlier KFOR

peacekeeping forces with 50,000 troops were considerably more agile.

"We are expected to work miracles," complained the very first UN

administrator, Bernard Kouchner of France, after periodically

reoccurring outbursts of ethnic hate.

This time the – unproven – claim that two Albanian boys were chased by

Serbs into the river Ibar and drowned led to the explosion of violence.

First in Kosovska Mitrovica and then in almost every other town and

city in the crisis-ridden province, including Prizren.

There, according to the debriefing of German policemen, about thousand

demonstrators marched through the city center on 17 March, chanting

"UCK, UCK" (KLA, KLA) and "UNMIK, ARMIK" (Unmik is the enemy). People

from the surrounding villages joined them; obviously they were

Islamists, recognizable by their long beards.

At 5:30 p.m. the first houses in the old part of the city began to

burn. The Serbian seminary was set on fire with the approval of the

gathered residents, stones flew at the civil administration building,

automobiles were destroyed. Not a sign of KFOR, although anxious

eyewitnesses requested intervention by German officers several times by

telephone.

Only when the flames threatened to spread to the surrounding houses did

Argentine UN police special forces approach, remaining at a safe

distance of 300 meters. Their attempt to disperse the crowd with

teargas was countered with a hail of stones and bottles. The South

Americans dropped their clubs and protective shields and fled.

The German KFOR appeared for the first time when the rioters took a

fire truck and drove to the UNMIK building. The appearance of the

military had an obvious effect. The mass continued on, nothing stopping

it in its march of destruction.

Between 6 p.m. and 9 p.m. the mass rioted in the old part of town on

the slope beneath the ruins of a Byzantine castle. The houses of

Serbian refugees were set on fire. A company of KFOR soldiers, guarding

the Serbian church of St. George from behind barriers of sandbags, fled

with the clergy and the remaining Serbs into the barracks. The

demonstrators applauded, set fire to the church and 56 more houses and,

in the end, the Orthodox church of the Holy Virgin of Ljevis, not far

from the municipal building. German defense minister Struck once had

said that this church is "a symbol of lasting peace brought by our

mission".

Some extremists continued on up the river Bistrica to the monastery of

Holy Archangels. The approach road could have been easily blocked with

a few armored vehicles, especially since master sergeant Udo Wambach

and 19 soldiers of the Bundeswehr were stationed in the 14th century

monastery.

About 200 demonstrators sent a delegation under a white flag to the

Germans and ensured them that nothing bad would happen to them, that

"we only want to burn down the monastery". The KFOR protectors

evacuated six monks and their two visitors to their armored vehicles

and drove them to the other side of the Bistrica. The monastery was

then burned down.

Master sergeant Wambach was expressly commended for his "outstanding

act" in mid-April by the deputy defense minister, Walter Kolbow, during

his visit to Prizren. No medal was issued but nevertheless a note was

included in his personnel file. According to the commendation, the

sergeant avoided "by his prudent behavior and courageous action, an

escalation of violence, preventing bloodshed and protecting the human

lives entrusted to him".

When night fell, the fire from the burning of the old part of town

illuminated the sky over Prizren. The next morning, on Thursday, March

18, smoke still could be seen rising above the rubble. But now

everything was calm.

At about 12:30 p.m. the mass again went into action. Since all Serbian

institutions were destroyed, the hatred of the Albanians was directed

now against the municipal administration, the UN civil administration

and the two police stations.

The first attacks began at about 3:00 p.m. and targeted the police

station in the city center. Calls for assistance directed to KFOR

remained unanswered. Stones flew at the house, automobiles were

overturned, no soldiers anywhere were to be seen. KFOR obviously had

not used the time to consider the reexamine its concept of engagement

in order to prevent renewed unrest.

This was followed by an attack on the police headquarters only a

kilometer away. Policemen from different nations, including Germans,

were exposed to a constant hail of stones and Molotov cocktails. The

extremists were receiving support and refills from a nearby gas

station. Gunshots rang out.

"We pleaded with KFOR for assistance," reported one official. "They