Informazione

http://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2014/06/09/fasc-j09.html

Nationalism and fascism in Ukraine: A historical overview

Part one

By Konrad Kreft and Clara Weiss

9 June 2014

This is the first part of a two-part article.

The Western media is seeking to downplay the prominent role of fascists in the new Ukrainian government. Several of the regime’s ministries are headed by members of the far-right Svoboda party, and the militias of the neo-fascist Right Sector are active in violently repressing resistance in the east of the country.

Both Svoboda and Right Sector played a crucial role in the February 22 coup in Kiev, which was strongly backed by Berlin and Washington. This is no coincidence. The close collaboration of Germany and the US with Ukrainian fascists has a long history, reaching back over the last hundred years.

The roots of Ukrainian nationalism

In contrast to many other European countries, there has never been a strong bourgeois national movement in Ukraine. Ukraine has been divided between Poland and Russia since the late Middle Ages. After the carve-up of Poland at the end of the eighteenth century, Ukraine became part of the Russian Empire. Only a section of what is now western Ukraine was integrated into the Hapsburg Empire.

The weakness of the Ukrainian national movement was due on the one hand to the country’s economic backwardness and lack of a strong middle class. Significant industrialisation occurred only in the era of the Soviet Union. On the other hand, a large proportion of the urban population consisted of Russians, Germans and Jews, while the rural population was mainly Ukrainian.

When bourgeois forces finally erected a Ukrainian nation-state, following the 1917 February Revolution’s overthrow of the tsar in Russia, they were immediately confronted with a revolutionary working class. The Bolsheviks, who seized power in Russia in October, received powerful support from the workers of Ukraine. Ever since then, bourgeois nationalism in Ukraine has been characterised by virulent anti-communism, pogroms against revolutionary workers and Jews, and attempts to win the support of imperialist powers.

The Social Democratic-dominated Rada (parliament), which proclaimed Ukraine’s independence in January 1918, tried to reach an agreement with Germany. After the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, however, the Soviet government was forced to cede Ukraine to Germany. When German troops marched into the country, the military dispensed with the Rada and established a dictatorship under Hetman (pre-eminent military commander) Pavlo Skoropadskyi, a landowner and former tsarist general. Skoropadskyi proceeded to make Kiev a rallying point for extreme right-wing and anti-Semitic politicians and military officers from all over Russia. (See: Anti-Semitism and the Russian Revolution: Part two)

Germany’s defeat in the First World War led to its forced retreat from Ukraine. Bloody battles engulfed Ukraine during the ensuing civil war in Russia. Supported by Western powers on Ukrainian soil in its fight against the Soviet government, the volunteer army under General Denikin committed horrific crimes and organised anti-Jewish pogroms. An estimated 50,000 Jews were murdered by the Whites in the second half of 1919 alone.

Symon Petliura, one the many Social Democrats who became nationalists, headed a directorate that took power in Kiev. This body also sought the backing of the Western powers in its war against the Soviet government and was responsible for the murder of more than 30,000 Jews. Both Petliura and Stepan Bandera, who emerged later as a leading figure, are regarded as role models by present-day Ukrainian nationalists.

Lenin advocated self-determination for Ukraine, and this democratic demand played a crucial role in winning the oppressed Ukrainian workers and peasants to the side of the Bolsheviks, who eventually won the civil war in 1921. In 1922, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic officially became part of the newly formed Soviet Union. However, western Ukraine remained under Polish rule.

Genuine independence from imperialism and development of national culture were possible in Ukraine only during the early years of the Soviet Union. These advances emerged from Lenin and Trotsky’s nationalities policy, which conceded to the nations within the Soviet confederation a comprehensive right to self-determination. The oppression of nationalities, as was common in the tsarist empire, was decisively rejected by the Bolsheviks.

The cultural life and material living standards of the Ukrainian masses underwent a dramatic improvement in the 1920s. The illiteracy rate declined sharply, as educational institutions and universities were established throughout the country. The Ukrainian language and culture were widely promoted, and this greatly stimulated intellectual life. As Leon Trotsky wrote in 1939, thanks to this policy, Soviet Ukraine became extremely attractive to the workers, peasants and revolutionary intelligentsia of western Ukraine, which remained enslaved by Poland.

However, the rise of the Stalinist bureaucracy brought an end to this nationalities policy. Lenin had attacked Stalin because of his centralist and bureaucratic tendencies in relation to the Georgian and Ukrainian questions. But after Lenin’s death, Stalin became increasingly ruthless in his attacks on non-Russian nationalities.

“The bureaucracy strangled and plundered the people within Great Russia, too,” wrote Trotsky in 1939. “But in the Ukraine matters were further complicated by the massacre of national hopes. Nowhere did restrictions, purges, repressions and in general all forms of bureaucratic hooliganism assume such murderous sweep as they did in the Ukraine in the struggle against the powerful, deeply-rooted longings of the Ukrainian masses for greater freedom and independence.” [1]

The Ukrainian peasants were particularly affected by the forced collectivisation of the late 1920s and early 1930s. Approximately 3.3 million people fell victim to this policy.

The devastating consequences of the nationalist polities of the Stalinist bureaucracy strengthened “nationalist underground groups… which were led by fanatical anti-Communists, successors of Petliura’s supporters and forerunners of Bandera’s people,” writes Vadim Rogovin in his book Stalin’s War Communism. [2]

Stalin’s murderous policies of repression played into the hands of Ukrainian nationalists and fascists, who agitated in the western parts of the divided Ukraine and collaborated with Hitler when he invaded the Soviet Union in 1941. Despite the crimes of Stalinism, however, the great majority of Ukrainians fought in the Red Army to defend the Soviet Union.

The crimes of the Ukrainian fascists in World War II

Among the most significant organisations that collaborated with the Nazis was the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN). Its members were recruited mainly from veterans of the Civil War who had fought on the side of Petliura against the Bolsheviks.

During the 1930s, the OUN carried out numerous terrorist attacks in Ukraine, Poland, Romania and Czechoslovakia. Its ideological head was Dmytro Dontsov (1883-1973), who became one of the leading ideologues of the Ukrainian extreme right-wing through his journalistic activities, among which were Ukrainian translations of Mussolini’s Dottrina del Fascismo ( The Doctrine of Fascism ) and excerpts from Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf .

Dontsov had earlier developed his thesis of “amorality.” According to historian Frank Golczewski, this asserted the obligation “to collaborate with every enemy of Great Russia, regardless of their own political goals.” It “created an ideological justification for the subsequent collaboration with the Germans” and the lineup of Ukrainian nationalists behind the United States during the Cold War. [3]

In 1940, the OUN split into the Bandera (B) and Melnyk (M) factions, which bitterly fought each other. Bandera’s more extreme group was able to attract more followers than Melnyk’s. It began by establishing Ukrainian militia (the Roland and Nightingale Legions) on German-occupied territory in Poland which, in league with the Wehrmacht (German army), invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941.

After the withdrawal of the Red Army from areas conquered by the Germans, the legions and special militias acted as auxiliary troops in countless massacres of Jews. Following the entry of the OUN-B into Lviv on June 29, 1941, the Bandera militias (Nightingale Legion) unleashed murderous pogroms against the Jews lasting several days. Ukrainian militia continued massacring Jews in Ternopil, Stanislau (today Ivano-Fankisk) and other places. Documentary evidence relating to the first few days of the Wehrmacht’s advance reveals that about 140 pogroms were perpetrated in western Ukraine, in which 13,000 to 35,000 Jews were murdered. [4]

On June 30, 1941, Bandera and his deputy head of the OUN-B, Yaroslav Stetsko, proclaimed the independence of Ukraine in Lviv. Stepan Lenkavski, the OUN-B government’s director of propaganda, openly advocated the physical extermination of Ukrainian Jewry.

The Nazis used their Ukrainian collaborators to commit murders and acts of brutality that were too disturbing even for the SS units. For example, SS task force 4a in Ukraine confined itself to “the shooting of adults while commanding its Ukrainian helpers to shoot [the] children.” [5]

Dealing with Ukrainian and other collaborators in the Soviet Union was a controversial issue in the Nazi leadership. While Alfred Rosenberg, one of the main Nazis responsible for the Holocaust, urged greater involvement of local fascist forces, Hitler opposed the nationalists’ so-called independence projects. On Hitler’s orders, the OUN-B leaders were eventually arrested and the Ukrainian legions disarmed and relocated.

From 1942, the Ukrainian militia served the Third Reich in the “anti-partisan campaign” in Belarus, in the “security service,” and as armed personnel in concentration camps. Bandera and Stetsko remained in custody in Sachsenhausen concentration camp until September 1944.

When Hitler’s armies went into retreat after their defeat at Stalingrad, members of the OUN legions returned to Ukraine and formed the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) in 1943. Immediately after his release by the German authorities, Bandera headed back to Ukraine to lead the UPA.

The UPA was supplied with German weapons and attempted to implement an extensive ethnic cleansing program in order to create the conditions for an ethnically pure Ukrainian state. In 1943 and 1944, the UPA organised massacres that claimed the lives of 90,000 Poles and thousands of Jews. It also brutally terrorised, tortured and executed Ukrainian peasants and workers who wanted to join the Soviet Union. The UPA went on to kill some 20,000 Ukrainians before the insurrection was completely crushed in 1953.

To be continued

Notes

[1] Leon Trotsky, “Problem of the Ukraine,” Trotsky Internet Archive

[2] Vadim Rogovin: Stalins Kriegskommunismus, Essen 2006, p. 377

[3] Frank Golczewski: Die ukrainische Emigration, (Hrsg.): Geschichte der Ukraine, Göttingen 1993, p. 236

[4] Per Anders Rudling: “The Return of the Ukrainian Far Right. The Case of VO Svoboda,” in: Ruth Wodak, John E. Richardson (ed.): Analyzing Fascist Discourse: European Fascism in Talk and Text, London 2013, pp. 228-255. The article is accessible online.

[5] Quoted in Christopher Simpson: Blowback. America’s Recruitment of Nazis and Its Effects on the Cold War, London 1988, p. 25

Nationalism and fascism in Ukraine: A historical overview

Part two

By Konrad Kreft and Clara Weiss

10 June 2014

This is the second of a two-part article. Part one was posted June 9.

The Ukrainian fascists during the Cold War

Immediately after World War II, the American secret service and military began recruiting high-ranking Nazis and Nazi collaborators for the ideological, political and military struggle against the Soviet Union. Fascists and war criminals from Germany and Eastern Europe who had been directly involved in the Holocaust and the murder of millions of Soviet civilians were utilized for covert activities by the US intelligence agencies or worked for propaganda outlets like Radio Free Europe.

According to Harry Rositzke, who was responsible at the CIA for secret operations inside the Soviet Union, “any bastard” was good “as long as he’s anti-Communist.” [6] The network that the CIA built up in the 1940s and 1950s in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union rested heavily on the web of Nazi collaborators.

A key role was played by Reinhard Gehlen, who had led Hitler’s military intelligence service on the Eastern Front and later became the first president of West Germany’s Federal Intelligence Agency (BND), responsible for foreign intelligence operations. From 1946, he worked for Washington and was able to utilise his old contacts among Ukrainian collaborators, within the anti-Soviet army of Russian General Vlasov, and within other Nazi networks.

The CIA’s first large-scale projects to destabilise the Soviet Union included intervention in the Ukrainian civil war. The predecessor to the CIA, the OSS, together with the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), had already supplied the underground war being waged by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) and the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists-Bandera (OUN-B) with materiel and logistics before the end of the world war. As well as military training, this included the parachute drop of agents into Soviet and Polish territory. [7] The guerrilla war in Ukraine became the prototype for similar operations by the CIA throughout the world during the Cold War.

The most important UPA liaison officer for the CIA was Mykola Lebed, whom American military intelligence had described in 1946 as a “well known sadist and collaborator of the Germans.” [8] In 1949, the CIA sponsored his entry into the United States and covered up his war crimes. In emigration, he led the OUN-Z, a split-off from Bandera’s arm of the OUN, which was funded by the United States. He provided the contact between the US and the UPA fighters.

After 1953, Lebed was involved in the management of the émigré publishing house Prolog, financed by the CIA, which disseminated nationalist, anticommunist and historically revisionist literature. From 1945 to 1975, Prolog also published material in Munich depicting the Ukrainian fascists as freedom fighters against communism and either denying or varnishing their participation in war crimes.

Since 1943, the UPA has worked on the myth of the “democratic freedom fighter” to make itself acceptable as an ally of American imperialism. The standard lie runs: the OUN/UPA fought for democracy against both the Nazis and the communists.

The Swedish historian Per Anders Rudling writes of the propaganda of the fascistic Ukrainian diaspora: “The line between scholarship and diaspora politics was often blurred, as nationalist scholars combined propaganda and activism with scholarly work. Lebed’s circle never condemned the crimes or the mass murders of the OUN, let alone admitted that they had taken place. On the contrary, it made denial, obfuscation, and white-washing of the wartime activities of the OUN and the UPA a central aspect of its intellectual activities.” [9]

For years, “The main conduits for smuggling” literature produced by the Western secret services “into Soviet Ukraine and Lviv in Western Ukraine were through Poland and Czechoslovakia.” [10]

When Polish-born Zbigniew Brzezinski became President Jimmy Carter’s national security adviser, the US increased its funding for anti-Soviet Ukrainian propaganda. In addition to literature and radio broadcasts, videocassettes were produced.

Under President Reagan, the strategy of destabilising the Soviet Union by boosting the nationalities question was intensified. The CIA produced material that was addressed to different ethnic groups in the Soviet Union and encouraged separatist-nationalist tendencies. In 1983, President Reagan received OUN-B leader and war criminal Yaroslav Stetsko at the White House, pledging, “Your struggle is our struggle. Your dream is our dream.” [11]

According to the Ukrainian nationalist historian Taras Kuzio, Prolog was able to produce $3.5 million worth of propaganda in the Soviet Ukraine thanks to the financial support of the US. This paid for publications and the use of new technologies, which, according to Kuzio, “had a great impact upon sustaining and increasing anti-regime activities and opposition groups in the late 1980s in the final push towards Ukrainian independence.” [12]

In West Germany, the BND, in which countless former Nazis were active, supported exiled nationalists in their anti-Soviet work. In Munich, where the BND is headquartered, a Ukrainian émigré centre was established after the war that distributed propaganda literature. Bandera and Stetsko, the two most important OUN-B leaders, also lived there under false names. In October 1959, Bandera was uncovered by the Soviet KGB and murdered in Munich. Stetsko, the exiled leader of the OUN-B, lived there until his death in 1986.

Many academics have covered up Western cooperation with Ukrainian fascists. During the 1950s, many books were published about the Second World War concealing the role of collaborators in Ukraine and Eastern Europe, or glorifying them. The media, too, largely kept quiet.

In his 1988 book Blowback: America‘s Recruitment of Nazis and Its Effects on the Cold War, American journalist Christopher Simpson, who uncovered the network of old Nazis in the service of the CIA, noted:

“Until recently, the US media usually could be counted on to maintain a discreet silence about émigré leaders with Nazi backgrounds accused of working for the CIA. According to declassified records obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, several mass media organizations in this country—at times working in direct concert with the CIA—became instrumental in promoting Cold War myths transforming certain exiled Nazi collaborators of World War II into ‘freedom fighters’ and heroes of the renewed struggle against communism.” [13]

Today’s war propaganda glorifying the fascists in Ukraine as model democrats and freedom fighters stands in this tradition.

The rise of Svoboda after 1991

After independence in 1991, Ukraine, like the rest of the former Soviet Union, saw far-right groups springing up like mushrooms. These ultra-right forces were encouraged by the imperialist powers and the Ukrainian state.

A systematic rehabilitation of the OUN and UPA began in the 1990s. In 1997, under the second Ukrainian president, Leonid Kuchma, a government commission on the OUN and UPA was established in which prominent historians participated. The reports produced by the commission in 2000 and 2005 whitewashed the role of the fascists, especially the OUN-B.

The commission’s objective was the ideological preparation of a law giving veterans of the Red Army and the OUN/UPA equal status. The breakthrough in the rehabilitation of these forces followed under President Viktor Yushchenko, who came to power in 2004 as a result of the Western-backed “Orange Revolution.” He then passed the law giving them the imprimatur of the state.

Svoboda supported Yushchenko in the “Orange Revolution.” Its chairman, Oleh Tyahnybok, elected as an independent parliamentary deputy, joined Yushchenko’s bloc Nasha Ukraina (Our Ukraine) and became a member of the parliamentary budget committee.

At that time, Tyahnybok said of the UPA/OUN-B veterans: “You fought against Moskali (a derogatory term for Russians), Germans, Yids and other scum… You are feared by the Mafia of the Moskali-Yids in the Ukraine the most.” This speech can be found on YouTube.

As a result of public pressure, Yushchenko’s bloc was unable to keep Tyahnybok and expelled him the same year. However, criminal charges for incitement were rejected.

Tyahnybok’s party was formed in 1991 under the name Social-National Party of Ukraine (SNPU) through the merger of various right-wing groups and student bodies. It renamed itself Svoboda (freedom) shortly before the Orange Revolution.

Immediately after he took office, Yushchenko began a broad-based campaign to rehabilitate the Ukrainian fascists and their collaboration with the Nazis. In July 2005, he founded an “Institute of National Remembrance,” committed the Ukrainian secret service SBU (once part of the KGB) to carry out propaganda, and supported the establishment of a Museum of the Former Soviet Occupation. As the director of the institute, he appointed Volodomyr Viatrovych, who as an ultranationalist activist was also director of the Centre for Research of the Liberation Movement, an institution of OUN-B successors. [14]

Several OUN and UPA fighters and nationalist leaders like Symon Petliura were officially honoured, with the state producing special stamps and commemorative coins bearing their portraits.

During his last year in power, Yushchenko ensured that the mass media, such as Channel 5, gave Svoboda a disproportionate amount of coverage. Tyahnybok and party ideologist Yuriy Mykhalchyshyn appeared on popular talk shows such as “Velyka polityka” (Big Politics) and “Shuster Live.” Especially following Svoboda’s electoral success in western Ukraine in 2009, the party achieved widespread media coverage. [15]

Yushchenko had monuments built in Lviv and Ternopil to commemorate war criminal Stepan Bandera, whom he declared to be a hero of Ukraine just days before the end of his presidency in 2010. After protests from Poland and the EU, the new president, Viktor Yanukovych, rescinded this honour, as well as that for the fascist Roman Shukhevych.

Swedish historian Per Anders Rudling described the ideological climate in 2013 with the words: “The hegemonic nationalist narrative is reflected also in academia, where the line between ‘legitimate’ scholarship and ultra-nationalist propaganda often is blurred. Mainstream book stores often carry Holocaust denial and anti-Semitic literature, some of which finds its way into the academic mainstream.” [16]

The Yushchenko regime’s collaboration with fascists was not limited to Svoboda. The openly anti-Semitic Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists (KUN), founded in 1992 as the successor organisation to the OUN with the participation of Stetsko’s widow Slava, joined Yushchenko’s bloc Our Ukraine in 2002 and remained in parliament until 2012. Party Chairman Svarytsh was in the first government of Yulia Tymoshenko and was justice minister in 2006 in Yanukovych’s anti-crisis alliance.

Under these conditions, Svoboda was able to triple its membership between 2004 and 2010, according to its own figures. Nonetheless, the party performed only modestly in elections. In the 2007 parliamentary elections, Svoboda won 0.78 percent of the vote, and in presidential elections in 2009, 1.43 percent.

By contrast, its vote in regional elections in western Ukraine was significantly higher. In local elections in 2010, the party achieved between 20 and 30 percent of the vote in eastern Galicia, and won 5.2 percent nationally. Since then, Svoboda’s stronghold has been the city of Lviv, where the OUN-B proclaimed the short-lived independent Ukraine in 1941.

In parliamentary elections in October 2012, which had the lowest turnout (58 percent) since independence, Svoboda entered the Verkhovna Rada (parliament) as the fourth-largest party, with 10.45 percent of the vote. Its highest vote percentages came from western Ukraine, with totals of between 30 and 40 percent in three administrative regions. On the other hand, the party barely achieved 1 percent in eastern Ukraine. In Lviv, Svoboda achieved more than 50 percent and in Kiev it was the second strongest party.

Svoboda leaves no doubt about its fascist orientation and its glorification of the Nazis. On 29 January 2011, on the occasion of a memorial event for the battle of Kruty in 1918, the party organised a large torchlight procession with autonomous right-wing groups and Nazi symbols.

On 28 April 2011, it celebrated the 68th anniversary of the establishment of the Galician division of the Waffen-SS. Along the route of the march, placards proclaimed “the pride of our nation.” The participants, with party ideologist Mykhalchyshyn at their head, chanted, “One race, one nation, one fatherland,” and hailed Bandera, Melnyk and Shukhevych as heroes of Ukraine.

On 30 June 2011, Svoboda commemorated the 70th anniversary of Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, as well as Stetsko’s renewal of the Ukrainian nation, in a people’s festival, where mock fighters appeared in SS uniforms.

In addition, Svoboda opened several restaurants in Lviv. In the dining room of one, an oversized portrait of Bandera was hung and jokes about Poles and Jews could be found on the toilet walls. Dishes on offer included “Hands up” (in German) and “battle serenade.” Local ultra-right football fans described Lviv on their banners as “Bandera town.” Streets in Lviv have been named after Nazi collaborators by Svoboda city councillors.

The young party ideologist Yuri Mykhalchyshyn, born in Lviv in 1982, founded a right-wing think tank in 2005 that he first named after Josef Goebbels and later Ernst Jünger. In his writings, he openly refers to the “heroic” legacy of fascists like Evgen Konovalets, Stepan Bandera and Horst Wessel. He has described the Holocaust as a “bright episode in European civilisation.”

The government and media’s hailing of fascism, which in Ukraine claimed millions of victims, has been met with disgust and opposition by large sections of the population. By contrast, the Western powers portrayed the Yushchenko regime, which pressed for the ideological and political rehabilitation of fascism, as a model democracy. At the same time, Svoboda and the right-wing paramilitary Right Sector received support from Western intelligence services and parties.

Svoboda maintains close ties to the far-right German NPD (National Democratic Party), which was described by judges in 2003 as a “state organisation” because its leadership was full of secret service operatives. In May 2004, the NPD welcomed a Svoboda delegation on a friendly visit to the state parliament in Dresden. The Christian Democratic Union-aligned Konrad Adenauer Foundation also provided Svoboda with a platform. The foundation invited Svoboda members to conferences and seminars on the lessons of the 2012 elections. At the time, Yanukovych had just been reelected.

The US Republican Party also has decades-long connections with Ukrainian fascists. The American government invested large sums of money in the preparation of the coup against Yanukovych. Victoria Nuland, US undersecretary of state for Europe, stated that Washington had “invested” around $5 billion in political projects in Ukraine over the past two decades.

On May 9, the government-aligned Russian newspaper Izvestia reported that a Right Sector member had flown to Washington at the end of April for talks with the US administration. Nuland offered Right Sector $5-$10 million to give up its weapons and transform itself into a party. But Dmytro Yarosh, leader of Right Sector, rejected the offer.

The strong support from Western governments for Ukrainian fascists is directed not only against workers in Ukraine, but against workers around the world. Berlin and Washington have deliberately built up fascist forces in Ukraine and are now using them to impose social attacks on the working class and prepare for a major war with Russia.

[PHOTOS:

1. Nazi Lt. General Reinhard Gehlen

2. Mykola Lebed

3. Stetsko meeting with Vice President Bush in 1983 ]

Notes

[6] Cited by Simpson, 1988, p. 159

[7] Taras Kuzio: US support for Ukraine’s liberation during the Cold War: a study of Prolog Research and Publishing Corporation, in Communist and Post-Communist Studies, no. 45, 2012, p. 53

[8] Simpson 1988, p. 166

[9] Per Anders Rudling: The OUN, the UPA and the Holocaust: A study in the manufacturing of historical myths, in the Carl Beck Papers in Russian & Eastern European Studies, no. 2107 (2011), p. 19. The article is accessibleonline.

[10] Kuzio, 2012, p. 56

[11] Russ Bellant: Old Nazis, the New Right and the Republican Party, Boston 1991, p. 72

[12] Kuzio 2012, p. 61

[13] Simpson 1988, p. 5

[14] Rudling 2013, p. 230

[15] Ibid ., p. 244

[16] Ibid ., p. 231

http://www.workers.org/articles/2014/06/08/nadja-tesich/

Nadja Tesich

Political activist, author, poet and filmmaker Nadja Tesich was born in Užice, Serbia, Yugoslavia, in 1939 and died Feb. 20 in New York City. She lived her life outspoken and full of righteous rage at the enormous destruction of U.S. wars and the glaring injustice and inequality that surrounded her. She felt collective pain personally, even physically, and identified with defenseless people targeted on the other side of the world or someone passing her on a busy street.

Nadja came to all events wearing always a splash of red — whether a red beret, red scarf or red jacket, or bearing red carnations. She loved Cuba and often said it was the only place she felt she could breathe.

At a memorial for Nadja on May 29, her family, friends and political comrades expressed the rainbow of ways she touched them. We remember her for her political activism, starting from defending the National Liberation Front of Vietnam in the 1960s.

From the beginning days of the International Action Center, Nadja was part of IAC life. She had fought against U.S. wars in Vietnam, coups in Congo, Chile and Greece; she was active in the mass demonstrations against the Iraq War in 1991 and again in 2003.

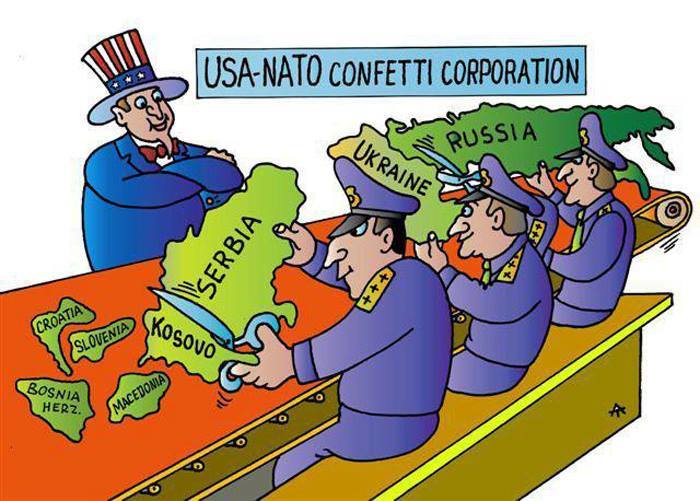

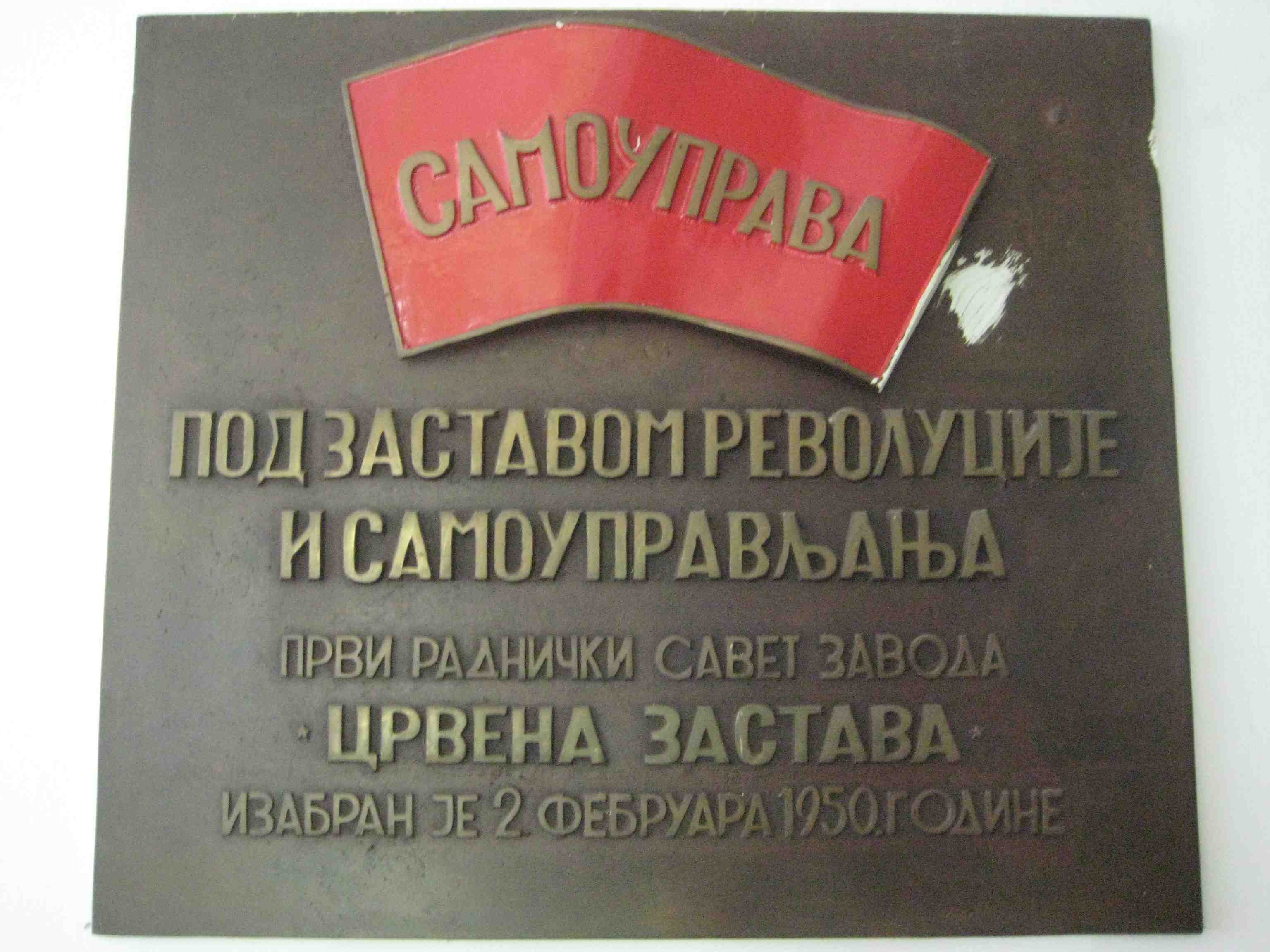

Nadja was even more intense in our common work attempting to defend her homeland, Yugoslavia, from an unrelenting assault by the imperialist governments of Western Europe and the United States. Tragically for most of the peoples of the Balkans, these years ended with the imposed disintegration of a once-sovereign socialist country into a half-dozen mini-states, now neocolonies of the NATO powers. At meetings, teach-ins and major rallies on Yugoslavia, Nadja was a driving force and a tortured soul of everything we did.

Tesich, whose family emigrated from Yugoslavia to the U.S. when she was a young teenager, has had four novels published: “Shadow Partisan” in 1996, “Native Land” in 1998, “To Die in Chicago” in 2010 and “Far from Vietnam” in 2012.

It is particularly striking to read “Shadow Partisan” and “To Die in Chicago” one after the other. The novels contrast on a close and personal level a hopeful coming-of-age in newly socialist Yugoslavia in the late 1940s with a cleareyed immigrant’s view of U.S. racism and a consumer-driven society without a future in the 1950s.

While studying in Paris in the 1960s, she worked in film as an actor and assistant to Eric Rohmer for the documentary, “Nadja in Paris.” She taught film at Brooklyn College in New York.

We should end with Nadja speaking in her own words, from her chapter in one of the IAC’s books, “NATO in the Balkans”:

“I was born in Serbia and have returned there every year, and I have also lived in France and in New York City most of my adult life. And most of my adult life, as a participant and as observer, I have opposed U.S. aggressions, murders, embargoes, wars. Some hidden, others less so.

Everything the U.S. does elsewhere — chaos and destabilization — it does equally at home. … It’s an amoral, mechanical monster whose heart is the beat of Wall Street. Up and down it goes. More and more it needs and it’s never enough. … Still it can be resisted. I remain optimistic. Machines break, after all.”

She often signed her messages “For our struggles now and for tomorrows that will sing!”

Nadja is survived by her son, Stefan; her sister-in-law, Rebecca; her grandchildren, Cole and Kaia;, her niece, Amy; and her many comrades in the struggle for peace, justice and socialism.

Nadja Tesich ¡Presente!

This article was adapted from IAC co-director Sara Flounder’s presentation at the memorial on May 29.

Annie Lacrox-Riz sulla Unione Europea e il D-Day

Mediokriteti kao osnivači Evropske Unije

Jaces-Marie Bourget

16/5/2014

Annie Lacroix-Riz podsjeća na Erica Hobsbawma, engleskog gorostasa historije, specijaliziranog za pitanje nacija i za nacionalizam. Tako je na primjer 1994 taj znanstvenik napisao „Kratko stoljeće“, knjigu koja vas zakucava za svoje istine, kao Arhimed u času kad je povikao „Eureka“! Za Hobsbawma XX stoljeće nije trajalo stotinu godina, već jedva 75 godina, od 1914 do 1991. Prije „Velikog rata“ svoje je vrijeme završavalo XIX stoljeće, gazeći po nogama stoljeća koje je nastupalo, a nakon „Zaljevskog rata“ na vrata je već kucalo XXI stoljeće. Engleski se historičar ljuti na kalendare, iako ima vlastiti način da ih ažurira. A što je bilo stom knjigom, koju uvijek treba držati u putnoj torbi, u slučaju da se treba ići na put? U Francuskoj ništa. Trebalo je čekati na prijevod u Monde diplomatique, da taj list upozna publiku sa Hobsbawmovim esejom. U Parizu, klika koja se bavi objavljivanjem knjiga sa područja historije nije imala petlje da objelodani taj britanski pogled, kojeg su odbacili, jer ga je napisao jedan marksist, dakle netko iz „predhistorije“ i neizostavno saučesnik gulaga.

Annie Lacroix-Riz proživljava slično ružno iskustvo unutar jedne „zajednice“, koja je samu sebe svela na tračarenje, a radi se o našim službenim historičarima, što svoja djela pišu u direktnom prijenosu televizije, sjedeći na koljenima Bernard Henri Lévyja. Oni su najčešće u prošlosti bili sjekire Komunističke partije Francuske (PCF) i kao svi konvertiti, pretvorili su se u Savanarole. Tim gore, jer ova povijesna istraživačica ima dobru reputaciju na ostatku planete i kod Anglosaksonaca, ima je čak i među vlastitim vrlo reakcionarnim kolegama. To što ti istraživači cijene jest radna sposobnost te gospođe, koja se hrani po kojim sedvičem u arhivima i na kraju u njima i prespava. Ona čita sve i sva na svim jezicima i sa Lacroix-Riz ulazimo u brutalnost činjenica: njeni navodi čine od njezinih čitalaca svjedoke historije.

Upravo je objavila knjigu o kojoj, budite u to sasvim sigurni, nećete nikada ništa čuti, a naziv joj je: „Aux origines du carcan européen (1900-1960“)/(„Izvor evropskih vratnih željeznih veriga (1900-1960)“/, izdanje kuće Le temps des Cirises.

U ovo vrijeme izbora njene riječi imaju izvjesnog smisla. Podsjetimo se na zahtjev, koji opravdava Evropsku Uniju kao dokaz: „Evropa je sredstvo za izbjegavanje rata“... U izvjesnim rečenicama Lacroix-Riz ga ponavlja i to podsjećajući na ratove u Jugoslaviji, na nasilne podjele i na današnju dramu Ukrajine. Povod je uvijek isti: kako bi potakle i promovirale vlastite interese Sjedinjene Države nastavljaju koristiti Evropu kao sredstvo. Ovoga puta u obračunu s Rusojom.

Rad francuske historičarke ide sve do izvorišta ovo sheme, do onog što bi se moglo nazvati „Euroamerikom“. Jer su klice još u ljusci ove današnje Evrope postojale mnogo prije stisaka ruku između De Gaullea ili Mitteranda i njemačkih kancelara.

Na kraju knjige bilanca istraživanje je: Evropa nije ništa drugo do redanje oportunih dogovora između velikih financijskih grupacija Njemačke i Francuske, dok su SAD imale ulogu čuvara uvažavanja sklopljenog bračnog ugovora. U početku radilo se o prikrivanoj idili, u najbrutalnijoj fazi rata 1914 godine. Sukob, koji je pobio ljude, doveo je do procvata industrije. Tako, podsjeća nas Lacroix-Riz, u augustu mjesecu 1914, kad su Nijemci ušli u Brey, došlo je do tajnog dogovora da se „ne bombardiraju“ postrojenja odnosno fabrike gospodina De Wandela. Golemi plakati sa natpisima „treba sačuvati“ bili su obješeni da se neka bitanga ne bi usudila oštetiti sveto vlasništvo te familije. Drugi primjer vrlo srdačnog sporazuma bila je onaj Henry Galla i njegovog kemijskog trusta Ugine. Taj je, preko svoje fabrike u švicarskom mjestu na rijeci Lonza, prodavao sve svoje električne proizvode i nužne kemijske artikle Njemačkoj, kako bi ova proizvodila strašno oružje kao cijanimid. Među poduzećima i za vrijeme rata vladao je mir.

Kao demonstracija te prekogranične strategije može poslužiti izostanak ratificiranja Versailleskog mira. Taj mir, koji je bio akt prestanka rata iz 1914 i koji je stavljao Njemačku pod teške sankcije, Sjedinjene Države su vrlo marljivo sabotirale, jer su se bojale „imperijalizma“ Francuske, koja bi bila isuviše jaka i isuviše laička. Dana 13 novembra Raymond Poincaré morao je popustiti pritiscima Washingtona. Dogovor je glasio ovako: vi ćete se povući iz Ruhra, prihvatit ćete dolazak jednog Komiteta američkih stručnjaka i financijaša, a mi ćemo prestati špekulirati i ometati vaš franak. Državni sekretar Hugues je predstavio taj ultimatum u ime bankara JP Morgana, a radi se o istoj banci, koja se danas nalazi u izvorištu svjetske financijske krize. U tom prekooceanskom ukazu /ediktu/proznaje se sakrivena ruka, koja će malo po malo napraviti i ispuniti unutarnjim sadržajem Evropu, koju poznajemo.

Evo jedne angdote. Mjeseca augusta 1928 , kad je Eaymod Poincaré predložio Gustavu Stresemannu, njemačkom ministru vanjskih poslova (koji je godine 1923 kratko vrijeme bio i kancelar) da naprave „zajednički front“ protiv „američke religije u odnosu na novac i protiv boljševičke opasnosti“, ovaj je to odbio. Za Lacroix-Riz Stresemann je jedan od „otaca Evrope“, zacijelo jako slabo poznat, on je pedala banaka sa Wall Street i uprvo pedala JP Morgana ili Younga. Godine 1925, u vrijeme potpisivanja ugovora u Locarnu, koji iscrtava ponovo granice posljeratne Evrope, baš tog Sresemanna predlaže Washngton kao velikog arhitekta, dok Aristide Briand i Francuska moraju spustiti vlastite guzove na rub ponuđene hoklice.

Stresemann će potpisati nešto što on u tajnosti smatra za „komad papira ukrašen izvjesnim brojem maraka“. Vlada Reicha je već potpisala tajne ugovore sa stranim nacionalistima, koji su joj skloni. Stresemann zna da je taj ugovor od samog svog rođenja prevaziđen, ali ipak, kad Hitler bude pokucao na vrata „Locarno“ će ostati sveta riječ u govorima političke desnice, bit će sinonim mira, iako je ustvari bio samo maska nacizma.

Gubitak francuske kontrole nad područjem Ruhra je tada prilika za potpisivanjem istinskog mira, mira za poslove. I tu se rađa „Međunarodni sporazum o čeliku“, koja će stvoriti „Pool ugljen-čelik“ a to znači našu Evropu, što su je ostvarile banke. Njemačka je prema dogovoru dobila 40,45% od Sporazuma, a Francuska 31,8%: rat je završen, jedan drugi rat sada može otpočeti. I taj drugi rat je došao. Godine 1943 Sjedinjene Države i Engleska stavljaju na papir „monetarni status“, koji mora stupiti na snagu po završetku ratnog konflikta. Pobjednik, Sjedinjene Države, „nametnut će državama, koje budu sudjelovale odustajanje od dijela vlastitog suvereniteta, kako bi održale fiksnim monetarni paritet“. Ta je želja upotrijebila dosta vremena da dočeka vlastito ostvarenje, ali sa ulogom koju danas igraju agencije za davanje obavjesti o rejtingu /rating/ te s obvezom, koja prisiljava Ujedinjene države Evrope da traže zajmove iskljčivo na privatnom tržištu, taj se plan napokon ostvaruje i respektira.

Dana 12 jula 1947 započela je u Parizu „Konferencija šesnaestorice“. Nacistički topovi su još bili vrući, kad su se Njemačka i Sjedinjene Države rasplakale nad sudbinom Ruhra. Tako da na margini Konferencije, Anglo-Amerikanci i Nijemci održvaju paralelne sastanke, kako bi ogulili kožu francuskim željama. No ovog puta barem Pariz se drži čvrsto. Izvan sebe od bijesa Amerikanci šaljuposebnog emisara da „ponovo napiše opći izvještaj sa Konferencije“. I da taj izvještaj bude razuman. Naročito su važne 6 točaka, koje je izdiktirao Clayton, državni sekretar za trgovinu. Te točke rezimiraju trgovinski i financijski program cijelog svijeta, dakle i Evrope, i to iz Washingtona. Sjedinjene Države zahtijevaju stvaranje izvjesne „trajne evropske organizacije, čiji će zadatak biti nadgledanje izvršenja evropskog programa“. Ta će naredba ugledati svjetlo pod nazivom organizacija za Evropsku Ekonomsku Kooperaciju (OECE), koja će biti anticipacija „naše“ Evrope. I Charles Henri Spaak , prvi predsjednik OECE je samo kancelar, koji primijenjuje ono što Amerikanci naređuju.

Što se tiče „očeva Evrope“, heroja koje danas slavimo glasanjem za Evropu, treba čitati ono što piše Lacroix-Riz, ukoliko ne želimo biti njezini sinovi. Jean Monnet? Bio je proglašen nesposobnim za vojnu službu 1914, a trgovao je alkoholnim pićima u vrijeme prohibicije, osnivač je Bancaamercana u San Francisku, bio je savjetnik Čang-Kaj-Šeka za račun Ameikanaca. Zatim se našao u Londonu 1940 godine te odbio da pristane uz Slobodnu Francusku, kako bi postao, 1943, Roosveltov izaslanik kod generala Girauda...Evo čovjeka idealnog profila za stvaranje slobodne Evrope. U toj porodičnoj igri, hoćete li još jednog „oca“ Evrope? Evo vam Robert Schuman, još jedna današnja ikona. U ljeto 1940 glasao je da se sva vlast dadne Pétainu, a kao nagradu za to, prihvatio je ulazak u njegovu vladu. Nakon rata Schuman je bio stavljen u status pokajanja, što je za katolika vrlo dobra praksa. Poslije, zaboravivši na prošlost, gurat će i navijati za kapitalističku Euro-Ameriku, kršćansku i takvu, koja će se razvijati u natkrivenim gredicama plastenika NATO-a.

Prije /i posloije/ „evropskog“ glasanja od 25 maja, treba pročitati „Aux origines du carcan européen“ /Porijeklo vratnih željeznih veriga Evrope/, jernakon te knjige kralj ostaje gol. Oni koji su, kao i François Hollande, uvjereni da „napustiti Evropu znači napustiti historiju“ moći će se uvjeriti kako predsjednik Francuske govori istinu, jer zaista treba napustiti historiju, koju ispisuju američki bankari.

(prijevod: Jasna Tkalec)

Le débarquement du 6 juin 1944 du mythe d’aujourd’hui à la réalité historique )

Annie Lacroix-Riz * | lafauteadiderot.net

Traduzione per Resistenze.org a cura del Centro di Cultura e Documentazione Popolare

Giugno 2014

Il trionfo del mito della liberazione americana dell'Europa

Nel giugno 2004, all'epoca del 60° anniversario (e primo decennale celebrato nel XXI secolo) dello sbarco alleato in Normandia, alla domanda "Quale è, secondo voi, la nazione che più ha contribuito alla disfatta della Germania", l'Ifop [Institut français d'opinion publique, agenzia francese di indagini statistiche e di mercato, ndt] diffuse una risposta rigorosamente inversa da quella raccolta nel maggio 1945: cioè rispettivamente 58 e 20% per gli Stati uniti e 20 e 57% per l'Urss [1]. Tra la primavera e l'estate 2004 c'èra stato un martellamento sul fatto che i soldati americani avevano, dal 6 giugno 1944 al 8 maggio 1945, attraversato l'Europa "occidentale" per restituirle l'indipendenza e la libertà rubata dall'occupante tedesco e minacciata dall'avanzata dell'Armata rossa verso ovest. Sul ruolo dell'Urss, vittima di questa "tanto spettacolare [inversione di percentuali] nel tempo" [2], non ci furono domande. Il 2014 (e il 70°) promette anche di peggio nella rispettiva presentazione degli "Alleati" della Seconda guerra mondiale, con sullo sfondo le invettive contro l'annessionismo russo in Ucraina e altrove [3].

La leggenda è cresciuta con l'espansione americana sul continente europeo, pianificata da Washington sin dal 1942 e portata a compimento con l'aiuto del Vaticano, tutore delle zone cattoliche e amministratore, prima, durante e dopo la Seconda guerra mondiale, della "sfera di influenza occidentale" [4]. Condotta in compagnia e in concorrenza con la Rft (poi con la Germania riunificata), questa spinta verso est ha preso un ritmo sfrenato dalla caduta del Muro di Berlino (1989): ha polverizzato gli "obiettivi di guerra" che Mosca aveva rivendicato nel luglio 1941 e raggiunto nel 1944 (recupero del territorio al 1939-1940) e nel 1945 (acquisizione di una sfera di influenza che riprendesse il vecchio "cordone sanitario" dell'Europa centrale e orientale, vecchia via germanica di invasione della Russia) [5]. Il progetto americano avanzava così rapidamente che Armand Bérard, diplomatico a Vichy e, dopo la Liberazione, consigliere d'ambasciata a Washington (dicembre 1944) e Bonn (agosto 1949), nel febbraio 1952 predisse che: "i collaboratori del Cancelliere [Adenauer] considerano in generale che il giorno in cui l'America sarà in grado di mettere in fila una forza superiore, l'Urss si presterà ad abbandonare i territori dell'Europa centrale e orientale che attualmente domina" [6]. Le premonizioni, allora sconcertanti, della "Cassandra" Bérard, sono nel maggio-giugno 2014 superate: l'antica Urss, ridotta alla Russia dal 1991, è minacciata alla sua porta ucraina.

L'egemonia ideologica "occidentale" che accompagna questo Drang nach Osten [Spinta verso Est] è stata assecondata dal tempo trascorso dalla Seconda guerra mondiale. Prima della Débâcle, "l'opinione francese" si era fatta "ingannare dalle campagne ideologiche" che avevano trasformato l'Urss in lupo e il Reich in agnello. La grande stampa, proprietà del capitale finanziario, l'aveva persuasa che l'abbandono dell'alleato cecoslovacco avrebbe preservato una pace duratura. "Una tale annessione sarà e può essere solamente il preludio di una guerra che diventerà inevitabile e, terminati gli orrori di questa, la Francia correrà il rischio più grande di conoscere la disfatta, lo smembramento e la vassalizzazione di ciò che rimarrà del territorio nazionale come stato in apparenza indipendente", aveva avvertito, due settimane prima di Monaco, un'altra Cassandra dell'alto Stato maggiore dell'esercito [7]. Ingannata e tradita dalle sue élite, "la Francia conobbe il destino annunciato ma i suoi operai e impiegati, subendo il 50% del taglio dei salari reali e perdendo 10-12 kg di peso tra il 1940 e il 1944, si lasciarono meno "ingannare dalle campagne ideologiche".

Percepirono la realtà militare certo più tardi rispetto "gli ambienti bene informati ", ma, in numero crescente col passare dei mesi, seguirono sugli atlanti o le carte della stampa collaborazionista l'evoluzione del "fronte est". Compresero che l'Urss, che richiedeva invano dal luglio 1941 l'apertura di un secondo fronte ad ovest che alleggerisse il suo martirio, portava da sola il peso della guerra. L'"entusiasmo" che suscitò in loro la notizia dello sbarco anglo-americano in nord Africa (8 novembre 1942), si era "spento" nella primavera successiva: "Oggi tutte le speranze sono rivolte alla Russia, i cui successi riempiono di gioia la popolazione tutta intera […] Ogni propaganda del partito comunista è diventata inutile […] il troppo facile confronto tra l'inspiegabile inattività degli uni e l'eroica azione degli altri preparano giorni difficili a coloro che si inquietano per il pericolo bolscevico", affermava un rapporto dell'aprile 1943 destinato al gaullista Bcra [Bureau Central de Renseignements et d'Action, il servizio informazioni francese, ndt] [8].

Se abbindolare le generazioni che avevano conservato il ricordo del conflitto era una questione complessa, l'esercizio è oggi divenuto agevole. Alla progressiva scomparsa dei suoi testimoni e attori, si è aggiunto il cedimento del movimento operaio radicale. Il Pcf, "partito dei fucilati", ha informato largamente e per molto tempo, ben al di là dei suoi ranghi, sulle realtà di questa guerra. Argomento che tratta meno volentieri in casa propria, sulla sua stampa, essa stessa in via di sparizione, battendo addirittura sulle colpe di un passato "stalinista" contemporaneo alla sua Resistenza. L'ideologia dominante, sbarazzatasi di un serio ostacolo, ha conquistato l'egemonia su questo come sugli altri campi. I circoli accademici non si oppongono più (addirittura associandosi) all'intossicazione scatenata sulla stampa scritta e audiovisiva o al cinema [9]. Pertanto, i preparativi e gli obiettivi del 6 giugno 1944 non sono chiariti dal film "Salvate il soldato Ryan" né dal lungo documentario "Apocalypse".

La Pax Americana vista da Armand Bérard nel luglio 1941

E' ben prima del "tornante" di Stalingrado (gennaio-febbraio 1943) che le élite francesi compresero le conseguenze americane della situazione militare nata dalla "resistenza […] feroce del soldato russo". Lo testimonia il rapporto datato metà luglio 1941 che il generale Paul Doyen, presidente della delegazione francese alla Commissione tedesca di armistizio di Wiesbaden, fece redigere dal suo collaboratore diplomatico Armand Bérard [10]:

1. Il Blitzkrieg era morto. "L'andamento dalle operazioni" contraddiceva le previsioni dei "dirigenti [del] III Reich [che…] non avevano previsto una resistenza tanto feroce del soldato russo, un fanatismo tanto appassionato della popolazione, una guerriglia tanto estenuante nelle retrovie, delle perdite tanto serie, un così tanto spazio davanti all'invasore, delle difficoltà tanto considerevoli di rifornimento e di comunicazioni. Le gigantesche battaglie di carri armati e aerei, la necessità, in assenza di vagoni a scartamento adatto, di assicurare i trasporti lungo strade dissestate per parecchie centinaia di chilometri comportano, per l'esercito tedesco, un consumo di materiale e di benzina che rischiano di diminuire pericolosamente le scorte insostituibili di carburanti e di gomma. Sappiamo che lo Stato maggiore tedesco ha predisposto riserve di benzina per tre mesi. Occorre che una campagna di tre mesi gli permetta di sottomettere il comunismo sovietico, di ristabilire l'ordine in Russia sotto un regime nuovo, di porre sotto sfruttamento tutte le ricchezze naturali del paese, in particolare i giacimenti del Caucaso. Tuttavia, senza preoccuparsi di ciò che mangerà domani, il russo incendia con il lancia-fiamme i suoi raccolti, fa saltare in aria i suoi villaggi, distrugge il suo materiale rotabile, sabota le sue aziende".

2. Il rischio di una disfatta tedesca (lungamente descritto da Bérard), costringeva i padroni della Francia a schierare un altro protettore all'imperialismo "continentale" scelto dopo la "Riconciliazione" degli anni 1920. Una tale svolta si rivelerà impossibile "nei mesi a venire", con il passaggio ineluttabile dall'egemonia tedesca a quella americana. Perché "gli Stati uniti, gia usciti soli vincitori dalla guerra del 1918, otterranno ancor di più dal conflitto attuale. Il loro potere economico, la loro alta civiltà, il numero della loro popolazione, la loro influenza crescente su tutti i continenti, l'indebolimento degli stati europei che potevano rivaleggiare con loro fa sì che, qualunque cosa accada, il mondo dovrà, nei prossimi decenni, sottoporsi alla volontà degli Stati uniti" [11]. Bérard scorgeva dunque fin dal luglio 1941 il futuro vincitore militare sovietico - che il Vaticano identificò chiaramente poco dopo [12] -, comprendeva che andava esaurendosi la guerra di attrito tedesca, del "solo vincitore ", per "potenza economica", che avrebbe praticato, in questa guerra come nella precedente, la "strategia periferica".

"Strategia periferica" e Pax americana contro l'Urss

Gli Stati uniti, non avendo mai subito l'occupazione straniera, né alcuna distruzione dopo la sottomissione del Sud agricolo (schiavistico) al Nord industriale, avevano relegato il loro esercito permanente a missioni tanto spietate quanto agevoli, prima di (ed eventualmente da) l'era imperialistica: liquidazione delle popolazioni indigene, sottomissione dei vicini deboli (il"cortile" latino-americano) e repressione interna. Per l'espansione imperiale, la consegna del cantore dell'imperialismo Alfred Mahan - sviluppare illimitatamente la Marina -, si era arricchita sotto i suoi successori delle stesse prescrizioni per l'aviazione [13]. Ma la modestia delle loro forze armate terrestri ne decretava l'inadeguatezza in un conflitto europeo. Una volta acquisita la vittoria per interposto paese, fornitore della "carne da cannone" (canon fodder), le forze americane si sarebbero dispiegate più tardi, come a partire dalla primavera 1918, sul territorio da controllare: sarebbero dunque partite dalle basi aeronavali straniere, quelle in Africa settentrionale che si aggiungevano dal novembre 1942 a quelle britanniche [14].

La Triplice intesa (Francia, Inghilterra, Russia) nel 1914 aveva condiviso l'impegno militare, spostatosi alla fine, visto il ritiro russo, soprattutto sulla Francia. E questa volta se lo sarebbe assunto l'Urss da sola, questa volta in una guerra americana che, secondo lo studio segreto del dicembre 1942 del Comitato dei capi di Stato maggiore congiunti (Joint Chiefs of Staff, JCS) si dava per regola di "ignorare le considerazioni di sovranità nazionale" dei paesi stranieri. Nel 1942-1943, il JCS: 1) sul conflitto in corso (e il precedente) giunse alla conclusione che la prossima guerra avrebbe avuto come spina dorsale i bombardieri strategici americani e che, semplice "strumento della politica americana, un esercito internazionale" incaricato di compiti subalterni (terrestri) avrebbe "internazionalizzato e legittimato la potenza americana"; e 2) innalzò l'interminabile e universale elenco delle basi nel dopoguerra, colonie degli "alleati" comprese (JCS 570). Niente avrebbe reso possibile il "tollerare delle restrizioni alla nostra capacità di far sostare e operare l'aereo militare nei e sopra certi territori sotto sovranità straniera", sentenziava il generale Henry Arnold, capo di Stato maggiore dell'Aviazione, nel novembre 1943 [15].

La "Guerra fredda" che trasforma l'Urss in "orco sovietico" [16] avrebbe disgiunto le confessioni sulla tattica che subordina l'utilizzo della "carne da cannone" degli alleati (momentanei), dagli obiettivi dei "bombardamenti strategici americani". Nel maggio 1949, firmato il Patto atlantico (4 aprile), Clarence Cannon, presidente della commissione delle Finanze della Camera dei rappresentanti (House Committee on Appropriations), glorificò i molto costosi "bombardieri terrestri pesanti capaci di trasportare la bomba atomica, che in tre settimane avrebbero polverizzato tutti i centri militari sovietici" e si rallegrò del "contributo che possono portare i nostri alleati […] inviando i giovani necessari ad occupare il territorio nemico dopo che l'avremo demoralizzato e annientato con i nostri attacchi aerei. […] Abbiamo seguito un piano simile durante l'ultima guerra" [17].

Gli storici americani Michael Sherry e Martin Sherwin lo hanno mostrato: era l'Urss, strumento militare della vittoria, il bersaglio simultaneo delle future guerre di conquista - e non il Reich, ufficialmente designato come nemico "delle Nazioni unite" [18]. Si comprende il perché leggendo William Appleman Williams, uno dei fondatori della "scuola revisionista" (progressista) americana. La sua tesi sulle "relazioni americano-russe dal 1781 al 1947" (1952) ha dimostrato che l'imperialismo americano non sopportava alcuna limitazione della sua sfera di influenzamondiale, che la "Guerra fredda", nata nel 1917 e non nel 1945-1947, aveva fondamenti non ideologici ma economici, e che la russofobia americana datava dall'epoca imperialista [19]. "L'intesa [russo-americana] vile e informale […] si era infranta sui diritti di passaggio delle ferrovie [russe] della Manciuria meridionale e dell'est cinese tra il 1895 e 1912". I sovietici ebbero in più l'audacia di sfruttare da sé la loro caverna di Ali Baba, sottraendo ai capitali americani il loro immenso territorio (22 milioni di kmq). Ecco ciò che generò "la continuità, da Theodore Roosevelt e John Hay a Franklin Roosevelt passando per Wilson, Hugues e Hoover, della politica americana in Estremo oriente" [20] - ma anche in Africa e in Europa, altri campi privilegiati "di una divisione e ripartizione del mondo" [21] americana rinnovata senza sosta dal 1880-1890.

Washington pretendeva di operare questa "divisione-ripartizione" a suo esclusivo beneficio, ragione fondamentale per la quale Roosevelt mise il veto a ogni discussione in tempo di guerra con Stalin e Churchill sulla ripartizione delle "zone di influenza". La cessazione delle ostilità gli avrebbe assicurato la vittoria militare a costi zero, visto lo stato pietoso del suo grande rivale russo, devastato dall'assalto tedesco [22]. Nel febbraio-marzo 1944, il miliardario Harriman, ambasciatore a Mosca dal 1943, faceva riferimento a due rapporti dei servizi "russi" del Dipartimento di stato ("Alcuni aspetti della politica sovietica attuale " e "La Russia e l'Europa orientale") per ritenere che l'Urss, "impoverita dalla guerra e a caccia della nostra assistenza economica […] una delle nostre principali leve per orientare un'azione politica compatibile ai nostri principi", non avrebbe avuto neanche la forza di sconfinare nell'Europa dell'est, di lì a poco americana. Si sarebbe accontentata per il dopoguerra di una promessa americana di aiuti, cosa che avrebbe permesso "di evitarci la creazione di una sfera di influenza dell'Unione sovietica sull'Europa orientale e i Balcani" [23]. Previsione da cui traspare un ottimismo eccessivo, visto che l'Urss non ha mai rinunciato ad assicurarsene una.

La Pax Americana nella parte francese della zona di influenza

I piani di pace sinarchici

Questa "leva" finanziaria era, tanto all'ovest che ad est, "una delle armi più efficaci a nostra disposizione per influire sugli avvenimenti politici europei nella direzione da noi desiderata" [24].

In vista di questa Pax americana, l'alta finanza sinarchica, cuore dell'imperialismo francese particolarmente rappresentato oltremare - Lemaigre-Dubreuil, capo degli olii Lesieur (e di società petrolifere), il presidente della banca di Indocina Paul Baudouin, ultimo ministro degli Affari esteri di Reynaud e primo di Pétain, ecc. -, negoziò, più attivamente dal secondo semestre 1941, col finanziere Robert Murphy, delegato speciale di Roosevelt in nord Africa. Futuro primo consigliere del governatore militare della zona di occupazione americana in Germania e uno dei capi dei servizi informazione, dall'Office of Strategic Services (OSS) di guerra alla Central Intelligence Agency del 1947, Murphy si era installato ad Algeri nel dicembre 1940. Questo cattolico integralista preparava lo sbarco degli Stati uniti in Africa settentrionale, trampolino verso l'occupazione dell'Europa, che sarebbe cominciata dal territorio francese quando l'Urss si apprestava a superare le sue frontiere del 1940-1941 per liberare i paesi occupati [25]. Queste trattative segrete furono tenute in zona non occupata, nell'"impero", tramite i "neutrali" filo-hitleriani Salazar e Franco, sensibili alle sirene americane, agli svizzeri e agli svedesi, e tramite il Vaticano, tanto preoccupato del 1917-1918 da assicurare una pace dolce al Reich vinto. Prolungati fino alla fine della guerra, inclusero sin dal 1942 dei piani di "ribaltamento dei fronti ", contro l'Urss, che trapelarono prima della capitolazione tedesca [26] ma non ebbero pieno effetto che dopo l'8-9 maggio 1945.

Trattando di affari economici immediati (in Africa settentrionale) e futuri (metropolitani e coloniali per il dopo-Liberazione), coi grandi sinarchici, Washington contava anche su di questi per escludere De Gaulle, ugualmente odiato delle due parti. In nessun caso perché fosse una sorta di dittatore militare insopportabile, conformemente a una duratura leggenda, al grande democratico Roosevelt. De Gaulle era sgradito solamente perché, per reazionario che fosse o fu, traeva la sua popolarità e la sua forza dalla Resistenza interna (soprattutto comunista): è a questo titolo che avrebbe intralciato il dominio totale degli Stati uniti, mentre una "Vichy senza Vichy" avrebbe offerto dei partner vilipesi dal popolo, dunque docili "perinde ac cadaver"[come cadaveri] alle disposizioni americane. Questa formula americana, alla fine destinata all'insuccesso visto il rapporto di forze generali e francesi, ebbe dunque per eroi successivi, dal 1941 al 1943, i cagoulards [terroristi di fede fascista, ndt] vichysti Weygand, Darlan poi Giraud, campioni riconosciuti della dittatura militare [27], così rappresentativi dei gusti di Washington per gli stranieri conquistati alla libertà dei suoi capitali e all'installazione delle sue basi aeronavali [28].

Spaventati dall'esito della battaglia di Stalingrado, gli stessi finanzieri francesi inviarono subito a Roma il loro devoto Emmanuel Suhard, strumento dal 1926 dei loro piani di liquidazione della Repubblica. Il cardinale-arcivescovo (di Reims) fu il Cagoule che nell'aprile 1940 aveva opportunamente liquidato il suo predecessore Verdier, chiamato a Parigi in maggio appena dopo l'invasione tedesca (del 10 maggio): i suoi mandanti e Paul Reynaud, complice dell' imminente putsch Pétain-Laval, lo spedirono a Madrid il 15 maggio, via Franco, a imbastire le trattative di "Pace" (capitolazione) col Reich [29]. Suhard fu dunque di nuovo incaricato di preparare, in vista della Pax americana, le trattative col nuovo tutore: doveva chiedere a Pio XII di porre "a Washington", via Myron Taylor, ex presidente dell'US Steel e dall'estate 1939 rappresentante personale di Roosevelt "vicino al papa", la seguente domanda: "Se le truppe americane saranno costrette a penetrare in Francia, il governo di Washington si impegna a che l'occupazione americana sia totale quanto l'occupazione tedesca?", all'esclusione di ogni altra "occupazione straniera (sovietica). Washington rispose che gli Stati uniti si sarebbero disinteressati della futura forma del governo della Francia e che si impegnavano a non lasciare che il comunismo si insediasse nel paese" [30]. La borghesia, notava un informatore del Bcra a fine luglio 1943, "non credendo più alla vittoria tedesca, conta […] sull'America per evitare il bolscevismo. Aspetta lo sbarco anglo-americano con impazienza, ogni ritardo gli appare come una sorta di tradimento". Questo ritornello fu cantato fino alla messa in opera dell'operazione "Overlord" [31].

… contro le speranze popolari

Al "borghese francese [che aveva] sempre considerato il soldato americano o britannico come naturalmente al suo servizio nel caso di una vittoria bolscevica", le RG [Renseignements généraux, servizio informazioni della Polizia nazionale, ndt] opponevano dal febbraio 1943 "il proletariato", che esultava: "i timori di vedere la sua vittoria sottratta dall'alta finanza internazionale si smorzano con la caduta di Stalingrado e l'avanzata generale dei sovietici" [32]. Da questo lato, al rancore contro l'inoperosità militare degli anglosassoni contro l'Asse si aggiunse la collera provocata dalla loro guerra aerea contro i civili, quelli delle "Nazioni unite" compresi. I "bombardamenti strategici americani", ininterrotti dal 1942, colpivano le popolazioni ma risparmiavano i Konzerne [complessi industriali] partner, IG Farben in testa come riportava a novembre "un industriale svedese molto importante e in strette relazioni con [il gigante chimico], di ritorno da un viaggio d'affari in Germania": a Francoforte, "le fabbriche non hanno sofferto", a Ludwigshafen "i danni sono insignificanti ", a Leverkusen "le fabbriche dell'IG Farben […] non sono state bombardate" [33].

Niente cambiò fino al 1944, quando un lungo rapporto di marzo sui "bombardamenti dell'aviazione anglo-americana e le reazioni della popolazione francese" denunciò gli effetti di questi "raid omicidi ed inefficaci": dal 1943 l'indignazione gonfiava tanto che scuoteva la base del controllo americano imminente del territorio. Dal settembre 1943 si erano intensificati gli attacchi contro la periferia di Parigi, dove le bombe erano "gettate a caso, senza scopo preciso e senza la minima preoccupazione di risparmiare delle vite umane". Quindi era toccato a Nantes, Strasburgo, La Bocca, Annecy, poi Tolone, che aveva "portato al colmo la collera degli operai contro gli anglosassoni": sempre le stesse morti operaie e poco o niente gli obiettivi industriali colpiti. Le operazioni preservavano sempre l'economia di guerra tedesca, come se gli anglosassoni "temessero di vedere finire troppo rapidamente la guerra". Così troneggiavano intatti gli altiforni la cui distruzione avrebbe paralizzato immediatamente le industrie della trasformazione, smettendo di funzionare per mancanza di materie prime". Si diffondeva "un'opinione molto pericolosa […] in certe parti della popolazione operaia che è stata colpita duramente dai raid. Ed è che i capitalisti anglosassoni non sono dispiaciuti di eliminare dei concorrenti commerciali e, allo stesso tempo, di decimare la classe operaia, di sprofondarla in uno stato di sconforto e di miseria che dopo la guerra gli renderà più difficile portare le sue rivendicazioni sociali. Sarebbe vano nascondere che l'opinione francese si è, da qualche tempo, raffreddata considerevolmente al riguardo degli anglo-americani" che indietreggiano sempre davanti "allo sbarco promesso […]. La Francia soffre indicibilmente […] Le forze vive del paese si esauriscono a una cadenza che si accelera di giorno in giorno, e la fiducia negli alleati prende una curva discendente. […] Istruiti dalla crudele realtà dei fatti, la maggior parte degli operai ripone oramai tutte le sue speranze nella Russia, il cui esercito è, a loro avviso, l'unico che possa superare in un futuro prossimo la resistenza dei tedeschi" [34].

È dunque in un'atmosfera di rancore contro questi "alleati" tanto benevoli con il Reich, prima e dopo il 1918, che ebbe luogo il loro sbarco del 6 giugno 1944. Collera e sovietofilia popolari si mantennero, dando al PCF un'eco che inquietava l'incombente stato gollista: "lo sbarco ha tolto alla sua propaganda una parte della forza di penetrazione", ma "il tempo abbastanza lungo impiegato dagli eserciti anglo-americani a sbarcare sul suolo francese è stato sfruttato per dimostrare che solo l'esercito russo era in grado di lottare efficacemente contro i nazisti. Le morti provocate dai bombardamenti e i dolori che suscitano servono anche da elementi favorevoli a una propaganda che pretende che i russi si battano secondo i metodi tradizionali e non se la prendano con la popolazione civile" [35].

Il deficit di simpatia registrata nella parte iniziale della sfera di influenza americana si mantenne tra la Liberazione di Parigi e la fine della guerra in Europa, come attestano i sondaggi dell'Ifop del dopo-Liberazione parigina ("dal 28 agosto al 2 settembre 1944") e dal maggio 1945 nazionale [36]. Fu un dopoguerra, lo si è detto, all'inizio progressivamente, poi brutalmente oppressivo. E' quindi di grande significato ricordare:

che dopo la battaglia delle Ardenne (dicembre 1944-gennaio 1945), la sola importante lanciata dagli anglosassoni contro le truppe tedesche (9.000 morti americani) [37], l'alto-comando della Wehrmacht trattò febbrilmente la resa "agli eserciti anglo-americani e il trasporto delle forze ad est";

che, a fine marzo 1945, "26 divisioni tedesche rimanevano sul fronte occidentale", al solo scopo di evacuare "verso ovest" dai porti del nord, "contro 170 divisioni sul fronte est" che combatterono accanitamente fino al 9 maggio (data della liberazione di Praga) [38];

che il liberatore americano che grazie alla guerra aveva raddoppiato il suo reddito nazionale, aveva perso sui fronti del Pacifico e dell'Europa 290.000 soldati dal dicembre 1941 all'agosto 1945 [39]: cioè gli effettivi sovietici morti nelle ultime settimane della caduta di Berlino, e 1% del totale delle morti sovietiche della "Grande guerra patriottica", intorno a 30 milioni su 50.

Dal 6 giugno 1944 al 9 maggio 1945, Washington finì di mettere a posto tutto o quasi per ristabilire il cordone sanitario che i rivali imperialisti inglesi e francesi avevano costruito nel 1919 e per trasformare in bestia nera il paese più caro ai popoli d'Europa (quello francese incluso). La leggenda della "Guerra fredda" meriterebbe le stesse correzioni di quella dell'esclusiva liberazione americana dell'Europa [40].

Note

[1] Frédéric Dabi, «1938-1944 : Des accords de Munich à la libération de Paris ou l'aube des sondages d'opinion en France», février 2012, http://www.revuepolitique.fr/1938-1944-laube-des-sondages-dopinion-en-france/, chiffres extraits du tableau, p. 5. Total inférieur à 100 : 3 autres données : Angleterre; 3 pays; sans avis.

[2] Ibid., p. 4.

[3] Campagne si délirante qu'un journal électronique lié aux États-Unis a le 2 mai 2014 a prôné quelque pudeur sur l'équation CIA-démocratie http://www.huffingtonpost.fr/charles-grandjean/liberte-democratie-armes-desinformation-massive-ukraine_b_5252155.html

[4] Annie Lacroix-Riz, Le Vatican, l'Europe et le Reich 1914-1944, Paris, Armand Colin, 2010 (2e édition), passim.

[5] Lynn E. Davis, The Cold War begins […] 1941-1945, Princeton, Princeton UP, 1974; Lloyd Gardner, Spheres of influence […], 1938-1945, Chicago, Ivan R. Dee, 1993; Geoffrey Roberts, Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939-1953. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2006, traduction chez Delga, septembre 2014.

[6] Tél. 1450-1467 de Bérard, Bonn, 18 février 1952, Europe généralités 1949-1955, 22, CED, archives du ministère des Affaires étrangères (MAE).

[7] Note État-major, anonyme, 15 septembre 1938 (modèle et papier des notes Gamelin), N 579, Service historique de l'armée de terre (SHAT).

[8] Moral de la région parisienne, note reçue le 22 avril 1943, F1a, 3743, Archives nationales (AN).

[9] Lacroix-Riz, L'histoire contemporaine toujours sous influence, Paris, Delga-Le temps des cerises, 2012.

[10] Revendication de paternité, t. 1 de ses mémoires, Un ambassadeur se souvient. Au temps du danger allemand, Paris, Plon, 1976, p. 458, vraisemblable, vu sa correspondance du MAE.

[11] Rapport 556/EM/S au général Koeltz, Wiesbaden, 16 juillet 1941, W3, 210 (Laval), AN.

[12] Les difficultés «des Allemands» nous menacent, se lamenta fin août Tardini, troisième personnage de la secrétairerie d'État du Vatican, d'une issue «telle que Staline serait appelé à organiser la paix de concert avec Churchill et Roosevelt», entretien avec Léon Bérard, lettre Bérard, Rome-Saint-Siège, 4 septembre 1941, Vichy-Europe, 551, archives du ministère des Affaires étrangères (MAE).

[13] Michael Sherry, Preparation for the next war, American Plans for postwar defense, 1941-1945, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1977, chap. 1, dont p. 39.

[14] Exemples français et scandinave (naguère fief britannique), Lacroix-Riz, «Le Maghreb: allusions et silences de la chronologie Chauvel», La Revue d'Histoire Maghrébine, Tunis, février 2007, p. 39-48; Les Protectorats d'Afrique du Nord entre la France et Washington du débarquement à l'indépendance 1942-1956, Paris, L'Harmattan, 1988, chap. 1; «L'entrée de la Scandinavie dans le Pacte atlantique (1943-1949): une indispensable "révision déchirante"», guerres mondiales et conflits contemporains (gmcc), 5 articles, 1988-1994, liste, http://www.historiographie.info/cv.html.

[15] Sherry, Preparation, p. 39-47 (citations éparses).

[16] Sarcasme de l'ambassadeur américain H. Freeman Matthews, ancien directeur du bureau des Affaires européennes, dépêche de Dampierre n° 1068, Stockholm, 23 novembre 1948, Europe Généralités 1944-1949, 43, MAE.

[17] Tél. Bonnet n° 944-1947, Washington, 10 mai 1949, Europe généralités 1944-1949, 27, MAE, voir Lacroix-Riz, «L'entrée de la Scandinavie», gmcc, n° 173, 1994, p. 150-151 (150-168).

[18] Martin Sherwin, A world destroyed. The atomic bomb and the Grand Alliance, Alfred a Knopf, New York, 1975; Sherry Michael, Preparation; The rise of American Air Power: the creation of Armageddon, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1987; In the shadow of war : the US since the 1930's, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1995.

[19] Williams, Ph.D., American Russian Relations, 1781-1947, New York, Rinehart & Co., 1952, et The Tragedy of American Diplomacy, Dell Publishing C°, New York, 1972 (2e éd).

[20] Richard W. Van Alstyne, recension d'American Russian Relations, The Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 12, n° 3, 1953, p. 311.

[21] Lénine, L'impérialisme, stade suprême du capitalisme, Essai de vulgarisation, Paris, Le Temps des cerises, 2001 (1e édition, 1917), p. 172. Souligné dans le texte.

[22] Élément clé de l'analyse révisionniste, dont Gardner, Spheres of influence, essentiel.

[23] Tél. 861.01/2320 de Harriman, Moscou, 13 mars 1944, Foreign Relations of the United States 1944, IV, Europe, p 951 (en ligne).

[24] Ibid.

[25] Lacroix-Riz, «Politique et intérêts ultra-marins de la synarchie entre Blitzkrieg et Pax Americana, 1939-1944», in Hubert Bonin et al., Les entreprises et l'outre-mer français pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Pessac, MSHA, 2010, p. 59-77; «Le Maghreb: allusions et silences de la chronologie Chauvel», La Revue d'Histoire Maghrébine, Tunis, février 2007, p. 39-48.

[26] Dont la capitulation de l'armée Kesselring d'Italie, opération Sunrise négociée en mars-avril 1945 par Allen Dulles, chef de l'OSS-Europe en poste à Berne, avec Karl Wolff, «chef de l'état-major personnel de Himmler» responsable de «l'assassinat de 300 000 juifs», qui ulcéra Moscou. Lacroix-Riz, Le Vatican, chap. 10, dont p. 562-563, et Industriels et banquiers français sous l'Occupation, Paris, Armand Colin, 2013, chap. 9.

[27] Jean-Baptiste Duroselle, L'Abîme 1939-1945, Paris, Imprimerie nationale, 1982, passim; Lacroix-Riz, «Quand les Américains voulaient gouverner la France», Le Monde diplomatique, mai 2003, p. 19; Industriels, chap. 9.

[28] David F Schmitz, Thank God, they're on our side. The US and right wing dictatorships, 1921-1965, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

[29] Index Suhard Lacroix-Riz, Le choix de la défaite : les élites françaises dans les années 1930, et De Munich à Vichy, l'assassinat de la 3e République, 1938-1940, Paris, Armand Colin, 2010 (2e édition) et 2008.

[30] LIBE/9/14, 5 février 1943 (visite récente), F1a, 3784, AN. Taylor, Vatican, chap. 9-11 et index.

[31] Information d'octobre, reçue le 26 décembre 1943, F1a, 3958, AN, et Industriels, chap. 9.

[32] Lettre n° 740 du commissaire des RG au préfet de Melun, 13 février 1943, F7, 14904, AN.

[33] Renseignement 3271, arrivé le 17 février 1943, Alger-Londres, 278, MAE.

[34] Informations du 15 mai, diffusées les 5 et 9 juin 1944, F1a, 3864 et 3846, AN.

[35] Information du 13 juin, diffusée le 20 juillet 1944, «le PC à Grenoble», F1a, 3889, AN.

[36] M. Dabi, directeur du département Opinion de l'Ifop, phare de l'ignorance régnant en 2012 sur l'histoire de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale, déplore le résultat de 1944 : «une très nette majorité (61%) considèrent que l'URSS est la nation qui a le plus contribué à la défaite allemande alors que les États-Unis et l'Angleterre, pourtant libérateurs du territoire national [fin août 1944??], ne recueillent respectivement que 29,3% et 11,5%», «1938-1944», p. 4, souligné par moi.

[37] Jacques Mordal, Dictionnaire de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Paris, Larousse, 1979, t. 1, p. 109-114.

[38] Gabriel Kolko, The Politics of War. The World and the United States Foreign Policy, 1943-1945, New York, Random House, 1969, chap. 13-14.

[39] Pertes «militaires uniquement», Pieter Lagrou, «Les guerres, la mort et le deuil : bilan chiffré de la Seconde Guerre mondiale», in Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau et al., dir., La violence de guerre 1914-1945, Bruxelles, Complexe, 2002, p. 322 (313-327).

[40] Bibliographie, Jacques Pauwels, Le Mythe de la bonne guerre : les USA et la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Bruxelles, Éditions Aden, 2012, 2e édition; Lacroix-Riz, Aux origines du carcan européen, 1900-1960. La France sous influence allemande et américaine, Paris, Delga-Le temps des cerises, 2014.

* Professore emerito di storia contemporanea, università Paris VII-Denis Diderot