Informazione

The Balkan floods and the break-up of Yugoslavia

By Paul Mitchell

20 May 2014

At least 44 people have died and tens of thousands have been left homeless in the worst-ever flooding to hit the Balkans.

Three months’ worth of rain fell in three days last week, causing the River Sava to burst its banks. It rises in the Alps of western Slovenia, forms the border between Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina and continues through Serbia to the capital Belgrade, where it joins the Danube. Thousands of landslides have been reported, destroying roads, railway lines and entire villages.

At least 27 people have died in Bosnia, including nine from the northeastern town of Doboj, devastated by what the regional police chief called a 3-4 metre high “tsunami” of water. About a third of the country is under water, affecting more than 1 million people.

The chairman of the Bosnian three-man presidency, Bakir Izetbegovic, declared that his country faced a “horrible catastrophe… We are still not fully aware of its actual dimensions.”

In Serbia, 12 bodies were recovered in the flooded town of Obrenovac, about 20 miles from the capital, Belgrade. More than 25,000 people have been evacuated and many more remain stranded.

The Nikola Tesla electricity plant in Obrenovac, which supplies most of Belgrade, is threatened, as is the coal-fired power plant at Kostolac, which provides over 20 percent of Serbia’s electricity needs.

Serbian Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic said, “What happened to us happens once in a thousand years, not hundred, but thousand.”

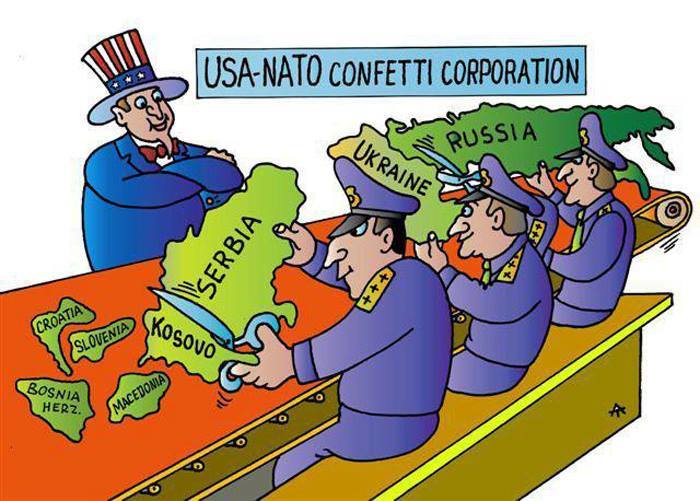

It is clear that the severity of the floods has been compounded by the fall-out from the break-up of the former Yugoslavia, the Bosnian War (1991-95) and the NATO bombardment of Serbia in 1999. Political tensions between the Balkan countries and the economic disaster, worsened by the 2008 global crisis, have continued to take their toll.

These factors have been ignored in most news reports, with comment limited to the danger from the exposure of some of the 120,000 landmines that remain from the Bosnian War and the disappearance of signs warning of minefields. Some 500 people have been killed by mines since 1995. Some reports also quote Sarajevo Mine Action Centre official Sasa Obradovic, who said, “Besides the mines, a lot of weapons were thrown into the rivers, lying idle for almost 20 years.” But that is as far as it goes.

In 1972, the Yugoslav government first attempted to monitor and control the River Sava, the country’s most important inland waterway, linking Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia and Montenegro. Its Sava River Basin Management Plan was one of the first in the world and attempted to reconcile the differing demands of the various republics—hydroelectric power in Slovenia, navigation for Croatia to its large inland port at Sisak, and agricultural needs in Bosnia and Serbia. Levees and reservoirs were built and waterways dredged. Further plans to improve navigation, prevent flooding and tackle pollution were drawn up in the 1980s.

However, these were thwarted by the break-up of the Yugoslav Republic and its descent into war. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the US and Germany both set about dismantling Yugoslavia by recognizing the breakaway republics of the old federation—Slovenia, Croatia, and then Bosnia—as independent sovereign states. The US was intent on exploiting the power vacuum created by the Soviet collapse to project its power eastward and gain control over the vast untapped reserves of oil and natural gas in the newly-independent Central Asian republics of the old USSR. The European powers, led by Germany, were anxious to stake their own claim.

Following years during which flood protection measures were ignored and infrastructure left unrepaired, numerous initiatives and commissions have been created to coordinate action, but these have borne little fruit as a result of the continuing economic and political situation.

In 2001, Bosnia-Herzegovina, the then-Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Croatia and Slovenia signed a “Letter of Intent” to set up “the Sava River Basin Initiative” to “utilize, protect and control the Sava River Basin water resources in a manner that would enable ‘better life conditions and raising the standard of population in the region’, and to find appropriate institutional frame [sic] in order to enhance the cooperation.”

A few years later the International Sava River Basin Commission was established. The River Sava, the largest tributary of the Danube, was also included in the International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River, which “commits the contracting parties to join their efforts in sustainable water management, including conservation of surface and ground water, pollution reduction, and the prevention and control of floods, accidents and ice hazards.”

In 2004, the United Nations weighed in with its “Development of Sava River basin Management Plan—Pilot Project,” saying, “There is a need of co-ordination, integration and data exchange for the whole basin. This includes co-ordination of operations in the Sava basin’s retention areas and water reservoirs to avoid the coincidence of floodwaters as well as the maintenance of high flow conditions in the Sava and Drina. National emergency plans, flood forecasting and intervention plans are essential in case of accidents.”

It called for the reconstruction of flood protection embankments and a new early warning system, which had been destroyed during the war.

Nearly 10 years later all that has really materialised is the Sava’s inclusion in the new European Flood Awareness System (EFAS), which came into operational service in 2012. Flood prevention and maintenance largely remain in the hands of national governments, which see these activities as low priority or easy targets when imposing austerity measures.

According to the book Water and Post-Conflict Peacebuilding, published earlier this year, the Sava River basin still remains “less developed than other river basins in Europe, water management suffers from inadequate institutional structures, inefficient operations, lack of water and sewage treatment plants and reduced financial capacity.”

Disputes continue over building hydroelectric power plants on the river and its tributaries. Large ships are still unable to navigate the top third of the river due to erosion, obstruction from bombed bridges, destruction of navigation infrastructure and mines due to the Balkan War and the NATO bombing of Serbia. The oil embargo on the country also gave rise to “severe deforestation” and soil erosion, increasing the risk of flooding. Sanctions prevented its scientists from attending international conferences.

Water and Post-Conflict Peacebuilding points out that a unified approach to the Sava River has also been thwarted by political tensions. The Montenegrin government has refused to take part in discussions over its future since its split from Serbia in 2006. Authorities of the two component parts of Bosnia-Herzegovina—Republica Srpska and the Croat-Muslim federation—hardly speak to each other and, in 2009, the Serbian government filed a lawsuit in the World Court accusing Croatia of genocide during the Balkan War in response to one filed by Croatia in 1999.

2) Riferimenti indicati nella comunicazione odierna della Ambasciata della rep. di Serbia a Roma -

vedasi l'immagine qui riportata ed anche: http://roma.mfa.gov.rs/news.php

<photo id="1" />

*** E' INCOMINCIATA ANCHE LA RACCOLTA PER LE SPEDIZIONI IMMEDIATE DI MATERIALI E VIVERI !

URGENTNE POTREBE UGROŽENOG STANOVNIŠTVA

HRANA

- konzerve – mesne prerađevine, riba,

- dječija hrana

- tjestenina

- so

- šećer

- riža

- grah

- ulje

- voda

HIGIJENA

- sredstva za dezinfekciju

- zaštitne maske

- higijenske rukavice

- radne rukavice

- sapuni

- deterđent za veš

- kaladont

- dječija higijena

- higijena za žene

OPREMA ZA SMEJŠTAJ UGROŽENIH

- poljski kreveti

- dušeci

- ćebad

- spužve

- posteljina – komplet

- sanitarni čvor

- odjeća i obuća

- šatori

- poljske kuhinje

- vreće za spavanje

- prostirke

OSTALE POTREBE

- lopate

- metle

- četke

- pumpe za izbacivanje vode

- isušivači prostorija

- pribor za dezifekciju

- boje za zidove

- pribor za bojanje

- drva - briketi

- sjemena

- peći za loženje

- grijalice

- plinski rešo – komplet sa bocom

- Lattine - Prodotti a base di carne, pesce,

- Alimenti per bambini

- Pasta

- Sale

- Zucchero

- Riso

- Fagioli

- Olio

- Acqua

IGIENE

- Disinfettanti

- Maschere di protezione

- Guanti igienici

- Guanti di lavoro

- Saponi

- Detergente per il lavaggio

- Dentifricio

- L'igiene dei bambini: pannolini

- Igiene per le donne: assorbenti

ATTREZZATURE PER SISTEMAZIONE DEGLI SFOLLATI

- Brandina Pieghevole con Materassino

- Materassi

- Coperte

- Spugne

- Biancheria da letto - Kit

- Toilette

- Abbigliamento e calzature

- Tende

- Fornelli da campeggio

- Sacchi a pelo

- Tappeti

- Forno per la cottura

- Riscaldatori

- Piastra al gas - completa di bottiglia

ALTRE ESIGENZE

- Pale

- Scope

- Pennelli

- Pompe d'acqua

- Unità essiccatoi

- acessori per disinfezione

- Colori per pareti

- Accessori per la pittura

- Legno

- Semi

BAMBINI

- giochi

- pennarelli

- matite colorate

- album da colorare

Milano 21:25 milano lampugnano

Brescia 23:00 via solferino autostazione

Verona 00:50 autostazione internazionale

Vicenza 02:00 autostazione viale milano

Padova 02:30 stazione centrale

sabato 24 maggio in piazza della vittoria genova parte il pullman Lasta prima delle ore 20:00 come rappresentate sul territorio vi chiedo un aiuto ... fate girare

Ko hoce da pomogne u subotu 24 maggio krece autobus Lasta Italia pre 20:00 ko predstavnik na teritorijum Lasta italije trazimo pomoc za Srbiju …. hranu dugo trajanje (pasta, paradais u konzervu pirinac … ) garderoba ... >>

(a cura del Coord. Naz. per la Jugoslavia ONLUS - https://www.cnj.it)

Da: Kappa Vu sas <kappavu.ud @ gmail.com>Oggetto: Presentazioni questa settimanaData: 19 maggio 2014 16:23:26 GMT+01:00

Knjigu će predstaviti prof. Jože Pirjevec, Stefano Lusa, Borut Klabjan i sam autor uz Gorazda Bajca kao moderatora. Predstavljanje će se odvijati na talijanskom jeziku.

German army conducts biggest military exercises since Cold War

By Sven Heymann

19 May 2014

Since last Monday, the German army has been conducting its largest military exercises since the 1980s. The entire orientation of the exercise makes clear that, amid the escalating tensions with Russia due to the crisis in Ukraine, the German army and its Western allies are once again preparing for a major war with Russia.

The operation, named “Jawtex” (Joint Air Warfare Tactical Exercise), has been planned for three years. Around 4,500 soldiers are involved from a total of 12 countries, including Germany, France, the US, Italy, Slovenia, Greece, Turkey, the Netherlands, and the non-NATO states Austria, Switzerland and Finland.

According to German army sources, it is not officially a NATO operation. However, other countries are involved—leaving no doubt that the cooperation is to be expanded and deepened within NATO, under the leadership of the German army. Finland’s involvement was particularly significant, since it is a state that is a non-NATO member with a 1,300-kilometre (808-mile) border with Russia.

Through the end of this week, practically the entire spectrum of tasks for “air combat forces” will be tested, according to the German army. The exercise is not confined to the air force, however. Jawtex was a “joined combined exercise,” involving the entire German army, Chief Lieutenant Gero Finke told Deutschlandfunk. The “collaboration between the air force, army and navy” is also to be tested.

According to German army sources, they will practice “overlapping combat scenarios between the air force, navy and ground units.” Another aim is to practice “comprehensive armed forces firing support.”

The sheer scale of the exercise confirms that the German army and its Western allies are already preparing for an open and major war, rather than the so-called special forces interventions in distant crisis regions of recent years.

Jawtex is “practically being conducted across Germany’s entire northern and northeastern territory,” the German army reported on its web site. Close to 100 planes and helicopters are involved, with around 150 takeoffs and landings daily. The exercise is being led by Brigadier General Burkhard Pototzky from the Holzdorf air base in Brandenburg.

It is not only the extent of the exercise that proves the German army is readying itself for war, however. The individual operations make clear the type of plans that are being pursued. An air landing operation with 900 soldiers is to be tested involving units of paratroopers, army aviation, and artillery.

The German army wrote on its web site about a long-range reconnaissance company that is participating: “Their task is the exposure of the enemy in the operating zone deep in enemy territory. They cannot make any mistake in the process. Once they are identified by the enemy, their mission is condemned to failure.”

In air space over northern Germany, the air force is taking over several flight corridors for days. Part of the exercise includes plans for flying at low altitudes of 70 metres (230 feet).

In Jagel, Schleswig-Holstein, the air force is practicing bombing missions. “For two weeks, pilots have to try to navigate through a cordon of radars and ground-to-air defence,” the NDR radio network wrote. Colonel Hans-Jürgen Knittlmeier commented, “It is practicing how to sneak in, how the opposing air defences can be overcome without suffering any losses.”

Such statements make the purpose of the Jawtex exercise clear. It is part of the transformation of German foreign policy, which is turning east again for a third time following two world wars in the previous century. Following the organisation of a coup in Ukraine by Germany, the US and its allies, preparations are underway for a military confrontation with Russia.

An interview with former German chancellor Helmut Schmidt in Friday’s edition of the Bild newspaper reflects the seriousness of the political crisis.

The 95-year-old warned that, as in 1914, Europe was standing on the edge of the abyss. “The situation seems to me to be increasingly comparable.” Though Schmidt said he did not want “to speak too soon about a third world war,” he said that “the danger that the situation could escalate as in August 1914 is growing daily.”

http://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2014/05/10/germ-m10.html

How the revival of German militarism was prepared

By Johannes Stern

10 May 2014

The German government’s aggressive action in Ukraine and the massive propaganda campaign accompanying it have surprised many. German politicians and opinion makers have almost unanimously backed the fascist-led coup in Ukraine. They seek to outdo each other with demands for tougher measures against Moscow and denounce the German people, the majority of whom are clearly opposed to the war propaganda.

What shocked many was carefully prepared. For more than a year, 50 leading politicians, journalists, academics and military and business figures discussed a more aggressive German foreign policy in a project under the auspices of the government-aligned Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP, German Institute for International and Security Affairs) and the Washington-based think tank German Marshall Fund (GMF).

At the conclusion of the consultations last autumn, a paper was published entitled “New power, new responsibility: Elements of a German foreign and security policy for a changing world.” It provides a blueprint for the policies that are now being implemented in practice in the form of sanctions against Russia and the rearming of NATO. With the document, the German bourgeoisie is returning to militarist, great power politics following two world wars and horrific crimes.

From the start, the SWP paper makes clear that Germany has to “lead more often and more decisively in the future” to pursue its global interests. The document states: “German security policy can no longer be conceived otherwise than globally. That said, Germany’s history, its location, and scarce resources are reasons to be judicious about its specific strategic objectives.”

The paper leaves no doubt about what the ruling class understands as “judicious.” As a “trading and export nation,” Germany “benefits from globalisation like few other countries” and relies on “demand from other markets, as well as on access to international trade routes and raw materials.” Therefore, the “overriding strategic goal” has to be “the preservation, protection and adaptation of the liberal world order.”

The openness with which the document asserts German spheres of influence and calls for these to be secured militarily is remarkable. “A pragmatic German security policy, particularly concerning costly and longer-term military deployments” must “concentrate primarily on the increasingly unstable European vicinity from Northern Africa and the Middle East to Central Asia,” the paper declares.

As “instruments of German security policy,” the document speaks of “a combination of civilian, police and military forces.” Military interventions should “range from humanitarian aid to military advice, support, reconnaissance, and stabilisation operations, all the way to combat operations.”

The call for Germany to assume a “leading role” runs like a thread through the paper, and is explicitly linked to military operations within the framework of NATO. The military alliance, with its “standing political and military structures, a broad range of instruments and capabilities for collective defence” is said to be “a unique amplifier of German security policy interests.”

The document continues: “Germany must use its increased influence to contribute to shaping the future orientation of NATO. It has an interest in the continued existence of a strong and effective NATO, because the alliance is a proven framework for political consultation and military cooperation with the US.”

But, ultimately, “more contributions” at the “military-operational level” are required. Europe and Germany have to adjust to this and “develop formats for NATO operations that rely less on US contributions.” The paper adds, “This requires greater investment in military capabilities and more political leadership.”

A key component of the project is how to impose the transformation of foreign policy in the face of widespread popular opposition. The paper complains of a “sceptical public,” which calls “the future direction” into question.

In a section headed “The domestic dimension of German foreign policy,” the paper warns that “a more prominent German role on the global stage” could “exacerbate issues of legitimacy at home.” It therefore bluntly calls for “policymakers and experts” to address the “public’s lack of understanding of foreign policy.” Policymakers must “learn to communicate their foreign policy goals and concerns more effectively to convince Germany’s own citizens, as well as international public opinion.”

The extent of the conspiracy

The way the document came about is just as important as its content. For almost a year, major figures from politics, the media, business, the universities, ministries, NGOs and foreign policy think tanks discussed among themselves to arrive at a common position.

An article that appeared on Zeit Online in early February described this process in detail. Under the revealing title “A Global Course,” Zeit editors Joachim Bittner and Matthias Nass indicated how the return to German great power politics was prepared.

They wrote: “This new foreign policy alliance is no accident. The change in course has a pre-history, a pre-history that can be reconstructed. It stretches back as far as November 2012, and it took place in different locations—Bellevue Castle, the official residence of the German president, in the Foreign Office at the Werderian Market, and under the auspices of the Foundation for Political Science, the German government’s think tank. Over months of repeated round table discussions, preparations were made for what culminated in Munich.”

The change in course was prompted by Germany’s abstention from the military intervention against Libya, which provoked harsh criticism of then-Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle. The authors of the article reported that “dissatisfaction with Germany’s lethargy had been mounting in the Berlin foreign policy community.”

They continued: “Four years of Westerwelle, four years without a clear course, but with even more frustration among the alliance partners. All of this had caused dissatisfaction to increase. The grumbling had been clearly audible.”

Then “for one year, from November 2012 to October 2013, a working group met in Berlin to discuss a foreign policy strategy for Germany. Officials from the chancellor’s office and the Foreign Ministry discussed together with representatives of think tanks, professors of international law, journalists and leading foreign policy representatives from all parliamentary fractions.”

The cooptation of the media

Die Zeit neglects to mention that Joachim Bittner was himself a member of the working group that elaborated the new foreign policy.

Nikolas Busse from the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zietung (FAZ) was added to the list of participants in the project. Bittner and Busse are among those German journalists with close ties to the German and American governments, the European Union (EU), NATO and numerous foreign policy think tanks.

As correspondent for the FAZ on NATO and the EU in Brussels, Busse is well connected to leading EU politicians and NATO military figures. He writes insider reports about NATO’s rearmament in eastern Europe. Already on February 25, three days after the coup in Ukraine and a month before Crimea joined with Russia, he reported under the headline “Turmoil in Ukraine: NATO Fears New Flashpoint in Europe” that military officials had “in the meantime even developed plans to defend alliance territory against Russia.”

Bittner was Zeit correspondent for Europe and NATO from 2007 to 2011, and in 2008 and 2009 a participant and reporter at the Brussels Forum, a partnership of the German Marshall Fund and the Bertelsmann Foundation.

On November 4 of last year, he published a programmatic article in the New York Times with the headline “Rethinking German Pacifism,” which advocated a more aggressive German foreign policy. In it he agitated against the “too deeply ingrained pacifism” among Germans and called for more “military interventions.”

If one wishes to understand why the German media has virtually unanimously beat the drums of war and not raised a critical voice, a study published in 2013 by the media studies academic Uwe Krüger is worth examining. It researches the links between leading German journalists and government circles in Germany and the United States and transatlantic think tanks. The study shows how the “journalistic output” of journalists is influenced by their links to the “US and NATO-oriented milieu.”

Professional scribblers like the co-editor of Die Zeit, Josef Joffe, and theSüddeutsche Zeitung’s Stefan Kornelius, both of whom have been leading the propaganda drive for war with Russia in recent weeks, are active in organisations concerned with foreign and security policy and the consolidation of transatlantic relations, “which are maintained to a great extent through the NATO common defence alliance.”

Their connections are wide-ranging. They participate regularly in the Munich Security Conference and have close ties to transatlantic think tanks such as the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies and the American Council on Germany. Joffe participates in the secretive, elite Bilderberg Conference, and Kornelius is a member of the executive of the German Atlantic Society. Both are involved in the German Society for Foreign Policy (DGAP), whose director, Eberhard Sandschneider, took part in the SWP project.

The emergence of Gauck, Steinmeier and Von der Leyen

While the ruling elite were agreeing on the key components of a new imperialist policy, the former pastor Joachim Gauck was installed as German president after a campaign in the press against his predecessor, Christian Wulff. It was Gauck’s job to announce the new shift in foreign policy publicly.

For this purpose, Gauck chose October 3, 2013. In his speech on the day commemorating German reunification, he summarised what had been discussed over the course of a year. He stated that Germany was “not an island” that could keep out of “political, military and economic conflicts.” It had to play a role in Europe and globally commensurate with its economic weight and influence.

Some of Gauck’s formulations were directly taken from the SWP paper. This was no accident. Gauck’s chief of staff, and one of the most important figures in the president’s office, is Thomas Kleine-Brockhoff. The former US correspondent for Die Zeit was among the initiators of the SWP project as then-director of the German Marshall Fund. Bittner reports in his article that “all Joachim Gauck’s speeches cross his desk.”

The timing of Gauck’s speech was deliberate. It took place only days after the 2013 federal election and set the agenda for coalition talks. This was seen with full clarity at the start of this year. Shortly after the assumption of power by the grand coalition, Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier (Social Democratic Party) and Defence Minister Ursula Von der Leyen (Christian Democratic Union) announced the course that had been decided at the Munich Security Conference.

In formulations almost identical to Gauck’s on October 3, Steinmeier declared that Germany must “be prepared to intervene earlier, more decisively and more substantially in foreign and security policy.” In a thinly veiled critique of his predecessor Westerwelle (Free Democratic Party), he attacked the “culture of restraint” and said, “Germany is too big just to comment on foreign policy from the sidelines.”

Steinmeier ran down a list of countries viewed as part of German imperialism’s sphere of influence. He declared: “Syria, Ukraine, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Mali, the Central African Republic, South Sudan, Afghanistan, tensions in East Asia—that is the incomplete list of hot spots in the coming year. Foreign and security policy will not run out of work.”

Von der Leyen struck a similar note. She stated that “for a country like Germany, indifference [is] not an option.” It is “a country of considerable size” and it has to “fulfil its international responsibilities.” This includes international missions by the EU and NATO. Concretely, she pledged to “strengthen the contribution in Mali,” to participate in the “destruction of the rest of the chemical weapons from Syria,” and to support “the coming European Union intervention in the Central African Republic.”

The incorporation of the Left Party and Greens

The so-called opposition parties in the German parliament were incorporated at the highest level in the foreign policy shift. Omid Nouripour for the Greens and Stefan Liebich for the Left Party participated in drawing up the SWP paper. Both are among the leading foreign policy spokesmen in their parties. Mouripour is a representative on the Parliamentary Defence Committee, and Liebich is a member of the Foreign Affairs Committee. In addition, Liebich sits on the Left Party’s executive.

The participation of the Greens is no surprise. The former pacifists were the strongest critics of Germany’s abstention in the Libyan war. Since they agreed on German participation in NATO’s war on Serbia under then-Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer, they have enthusiastically supported every foreign intervention by the German army.

The incorporation of the Left Party is of particular significance. The party gives up its pacifist phrases at a point when German imperialism returns once again to the world stage. Liebich is a member of several foundations and think tanks, including the Atlantic Bridge and the DGAP.

While Liebich cooperated in the development of the new foreign policy under the auspices of the SWP, an agreement was reached within the Left Party in favour of a more aggressive foreign policy. Already last autumn, a collection of essays was published by WeltTrends with the title “Left foreign policy: perspectives for reform.” In it, leading Left Party politicians argued in similar terms as the SWP strategy paper. They spoke out in favour of military deployments, closer transatlantic cooperation with the US, and a greater international role for Germany.

The Left Party is now implementing this course in practice. In April, five party members, led by Liebich, voted together with the government parties for a foreign intervention by the German army. This marked the first-ever vote by Left Party delegates in support of a German military deployment. Another leading Left Party member, Christine Buchholz of the state capitalist Marx21 group, accompanied Defence Minister Von der Leyen on the latter’s recent visit to German troops in Africa.

Ideological support from the universities

An important component of the foreign policy shift is the involvement of German universities. Professors from the Free University Berlin, the Friedrich Schiller University in Jena, the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University in Frankfurt/Main, the European Viadrina University in Frankfurt/Oder, and the Humboldt University in Berlin took part in the discussions sponsored by the SWP and GMF.

The incorporation of the universities in the state’s war propaganda is a violation of the principle of the independence of research and teaching. There are horrific precedents for such collaboration in German history—notably, professors in the Third Reich who sought to provide a scientific basis for racist ideology, such as Carl Schmitt, who interpreted the law in the spirit of the Nazis, and Martin Heidegger, who provided Hitler with his philosophical blessing.

Significantly, the legal scholar Georg Nolte represented the Humboldt University in the discussions. He is the son of historian Ernst Nolte, who provoked the so-called Historians’ Dispute in 1986 by downplaying the crimes of the Nazis.

The revival of German militarism requires that the history of the twentieth century be rewritten and the crimes of German imperialism in two world wars be trivialised. Humboldt University has specialised in this task for some time. The head of the department of Eastern European History, Jörg Baberowski, has dedicated his work to the rehabilitation of Ernst Nolte. Der Spiegelrecently cited Baberowski saying, “Nolte was done an injustice. He was historically correct.”

In the future, the state and big business will provide the war ideologists in the universities with even greater quantities of research funds to enable them to serve, under the cover of science, as the ideological cadre-trainers of militarism.

In the SWP document it states: “A more complex environment with shortened response times also requires better cognitive skills, knowledge. Knowledge, perception, understanding, judgment and strategic foresight: all these skills can be taught and trained. But that requires investments—on the part of the state, but also on the part of universities, research institutions, foundations, and foreign policy institutions. The goal must be to establish an intellectual environment that not only enables and nurtures political creativity, but is also able to develop policy options quickly and in formats that can be operationalised.”

This is the new Orwellian language of German imperialism in the twenty-first century. Behind conceptions like “intellectual environment,” “political creativity,” “strategic foresight” and “quick and operational political options” stands the call to once again “think militarily” and return to a “politically creative” policy of war. This is the way in which the ruling class is responding to the deepest crisis of capitalism since the 1930s.

The scale of this war conspiracy and its meticulous preparation is a serious warning. On two occasions in the last century, German imperialism threw the world into the abyss. The international working class cannot and will not allow it to happen a third time. This underscores the critical role of the International Committee of the Fourth International in building the new, revolutionary leadership of the working class in Europe and internationally.