Informazione

[ Pochi giorni fa, alla periferia di Skopje, Fazli Veliu, parlamentare

dell'Unione Democratica per l'Integrazione (il partito di Ali Ahmeti,

che raccoglie i terroristi dell'UCK macedone protagonisti delle

violenze del 2001-2002) nel corso di una dimostrazione pubblica ha

urlato: "Il prossimo anno celebreremo un'altra vittoria

dell'unificazione nazionale pan-albanese... La nostra storia gloriosa

non e' terminata. Essa mira ad un obiettivo e ad una strategia

nazionali: Albania, Kosovo, Kosovo orientale, Serbia meridionale ed

Arberia". ]

http://www.slobodan-milosevic.org/news/dnevnik081504.htm

Macedonian Albanian MP calls for pan-Albanian unification at rally -

daily

BBC Monitoring - August 15, 2004

Text of report by B.G.: "The DUI called for pan-Albanian unification",

published by Macedonian newspaper Dnevnik on 13 August

"The Radusa Radusha in Albanian rally next year should celebrate

another victory of pan-national and pan-Albanian unification." That

was the message of DUI Democratic Union for Integration - BDI in

Albanian Assembly deputy Fazli Veliu last night, at the celebration in

the Skopje village of Radusa.

"Our glorious history is not over. It is still pursuing a national

goal and strategy: Albania, Kosovo, Eastern Kosovo southern Serbia and

Arberia," Veliu said.

A few thousand residents of that village attended the rally at which

the members of the former ONA National Liberation Army - UCK in

Albanian celebrated the third anniversary of the end of the fighting.

There were only Albanian flags at the celebration. The UCK flag was

flying over the central stage, and the banners read: "Welcome to the

impregnable fortress of Radusha," "This is the stronghold of Albanian

national power" and "Freedom and peace".

The audience was addressed also by Rafiz Aliti, vice-chairman of the

DUI.

"We were forced to choose a road to freedom in the language of weapons

as all other methods had been exhausted. The Albanian people had been

discriminated against and underprivileged. The war in Radusha was

provoked by military and police mercenaries commanded by anti-Albanian

and anti-civilian officers. Our fierce defence of Albanian existence

and our readiness for sacrifice forced the international and domestic

forces to change their position and arrive at the right conclusion,"

Aliti pointed out. He said that during the fighting in this region

"young people from Kosovo came to help as a compensation for what the

young people of this region gave in the Kosovo war against the Serbian

forces".

The DUI had the largest representation at the rally. No prominent

leaders of other Albanian political parties could be seen. The rally

was not attended by a single representative of the parties in the

Macedonian political bloc. Answering reporters' questions, Rafiz Aliti

said that he expected that the Ohrid Accord would be implemented "to

the smallest detail". "We are not happy with the speed of the

implementation of the Ohrid Accord but I do not think that anybody

should have doubts that the accord will be implemented. It is

Macedonia's future. Every war ends in an agreement and we stand firmly

behind this agreement," he said.

Aliti does not think that there are destabilization tendencies in this

country.

"I think that the devolution process will come off regardless of the

protests. There have always been protests and they will never

disappear. It is just impossible to make all citizens happy. I think

that 70 per cent of the citizens will be happy. We are building

Macedonia's future with this law," he said.

SOURCE: Dnevnik, Skopje, in Macedonian 13 Aug 04 pp 1, 3

Copyright 2004 British Broadcasting Corporation

BBC Monitoring Europe - Political

Supplied by BBC Worldwide Monitoring

Posted for Fair Use only.

dell'Unione Democratica per l'Integrazione (il partito di Ali Ahmeti,

che raccoglie i terroristi dell'UCK macedone protagonisti delle

violenze del 2001-2002) nel corso di una dimostrazione pubblica ha

urlato: "Il prossimo anno celebreremo un'altra vittoria

dell'unificazione nazionale pan-albanese... La nostra storia gloriosa

non e' terminata. Essa mira ad un obiettivo e ad una strategia

nazionali: Albania, Kosovo, Kosovo orientale, Serbia meridionale ed

Arberia". ]

http://www.slobodan-milosevic.org/news/dnevnik081504.htm

Macedonian Albanian MP calls for pan-Albanian unification at rally -

daily

BBC Monitoring - August 15, 2004

Text of report by B.G.: "The DUI called for pan-Albanian unification",

published by Macedonian newspaper Dnevnik on 13 August

"The Radusa Radusha in Albanian rally next year should celebrate

another victory of pan-national and pan-Albanian unification." That

was the message of DUI Democratic Union for Integration - BDI in

Albanian Assembly deputy Fazli Veliu last night, at the celebration in

the Skopje village of Radusa.

"Our glorious history is not over. It is still pursuing a national

goal and strategy: Albania, Kosovo, Eastern Kosovo southern Serbia and

Arberia," Veliu said.

A few thousand residents of that village attended the rally at which

the members of the former ONA National Liberation Army - UCK in

Albanian celebrated the third anniversary of the end of the fighting.

There were only Albanian flags at the celebration. The UCK flag was

flying over the central stage, and the banners read: "Welcome to the

impregnable fortress of Radusha," "This is the stronghold of Albanian

national power" and "Freedom and peace".

The audience was addressed also by Rafiz Aliti, vice-chairman of the

DUI.

"We were forced to choose a road to freedom in the language of weapons

as all other methods had been exhausted. The Albanian people had been

discriminated against and underprivileged. The war in Radusha was

provoked by military and police mercenaries commanded by anti-Albanian

and anti-civilian officers. Our fierce defence of Albanian existence

and our readiness for sacrifice forced the international and domestic

forces to change their position and arrive at the right conclusion,"

Aliti pointed out. He said that during the fighting in this region

"young people from Kosovo came to help as a compensation for what the

young people of this region gave in the Kosovo war against the Serbian

forces".

The DUI had the largest representation at the rally. No prominent

leaders of other Albanian political parties could be seen. The rally

was not attended by a single representative of the parties in the

Macedonian political bloc. Answering reporters' questions, Rafiz Aliti

said that he expected that the Ohrid Accord would be implemented "to

the smallest detail". "We are not happy with the speed of the

implementation of the Ohrid Accord but I do not think that anybody

should have doubts that the accord will be implemented. It is

Macedonia's future. Every war ends in an agreement and we stand firmly

behind this agreement," he said.

Aliti does not think that there are destabilization tendencies in this

country.

"I think that the devolution process will come off regardless of the

protests. There have always been protests and they will never

disappear. It is just impossible to make all citizens happy. I think

that 70 per cent of the citizens will be happy. We are building

Macedonia's future with this law," he said.

SOURCE: Dnevnik, Skopje, in Macedonian 13 Aug 04 pp 1, 3

Copyright 2004 British Broadcasting Corporation

BBC Monitoring Europe - Political

Supplied by BBC Worldwide Monitoring

Posted for Fair Use only.

"...Il governo montenegrino sacrifica il fiume Tara affinché, nei

prossimi decenni, EFT possa mantenere il suo monopolio sul mercato

dell’energia elettrica montenegrina. La compagnia con sede a Londra è

il principale fornitore di energia elettrica nei Balcani ed il

principale importatore per il Montenegro. I rappresentanti governativi

a Podgorica hanno numerosi ed oscuri legami con la EFT..." Ma si noti

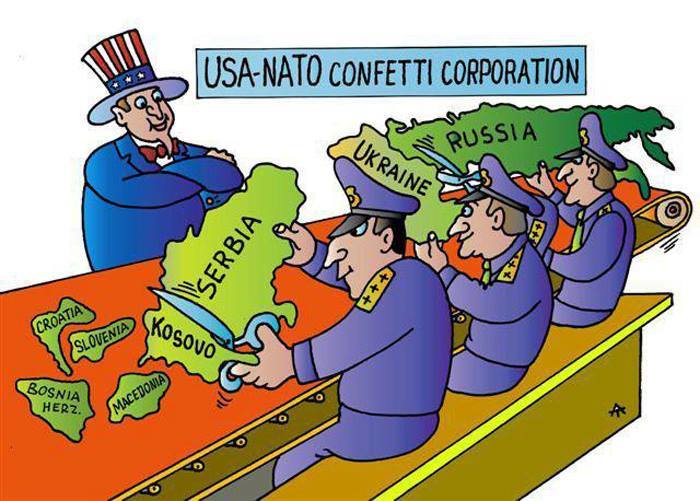

anche l'effetto devastante della frammentazione della Jugoslavia

sull'approvvigionamento energetico di ciascuna di queste repubblichette

para-indipendenti: costrette oggi, nonostante le enormi risorse dei

propri territori, a litigarsi e/o spartirsi con difficolta'

opportunita' e progetti che sono nell'interesse di tutti i loro

cittadini. I quali peraltro, da entrambe le parti del "confine", sono

lo stesso popolo! E l'unica a giovarsi di questa situazione e' la

grande impresa monopolistica straniera... (I.S.)

http://auth.unimondo.org/cfdocs/obportal/

index.cfm?fuseaction=news.notizia&NewsID=3298

Montenegro : una catastrofe ambientale annunciata per il fiume Tara

Stanno per iniziare i lavori per la costruzione di una centrale

idroelettrica a Buk-Bijela, in Republika Srpska. Il progetto causerà lo

riempimento del canyon del fiume Tara in Montenergo. Perché Milo

Djukanovic si è lanciato in quest’avventura?

(10/08/2004)

Un articolo di Milka Tadic-Mijovic – Monitor

Traduzione a cura di Le Courier des Balkans

Sono state avviate le procedure per la costruzione di una centrale

idroelettrica a Buk-Bjiela e la conseguente inondazione del canyon del

fiume Tara. Il governo del Montenegro, senza aver promosso alcun

dibattito tra gli esperti in materia, e dopo negoziazioni in sordina,

ha sottoscritto l'accordo sulla costruzione congiunta della centrale

idroelettrica con la Republika Srpska. La centrale sarà costruita in un

altro stato, appunto la Bosnia Erzegovina, ma le acque del fiume Tara e

Piva inonderanno il territorio montenegrino.

Le negoziazioni sulla costruzione della centrale idroelettrica sono

state avviate da anni ma, a partire dal 1998, si sono intensificate. Il

climax della vicenda lo si raggiunge nell’aprile scorso quando in

Republika Srpska è stata convocata una gara d’appalto alla quale sono

state recapitate tre proposte per la costruzione della centrale. Solo

tra sei mesi si saprà chi avrà vinto il contratto.

Ma perché Milo Djukanovic si è lanciato in un’avventura che suscita le

forti critiche sia degli esperti che degli innamorati del fiume Tara?

Questi gli argomenti che fornisce il governo: il progetto Buk-Bijela è

il più grosso investimento che si progetta nella regione, con un costo

stimato di 300 milioni di euro; la costruzione durerà almeno cinque

anni; vi saranno occupati più di 3000 operai; ne usciranno rinnovate

tutte le infrastrutture del nord-ovest del Montenegro … e, questione

ritenuta cruciale, la centrale avrà una produzione di 450 megawatt/ora,

della quale un terzo andrà al Montenegro e contribuirà a diminuire

l’attuale deficit energetico che lo caratterizza.

I vantaggi, sottolineano i responsabili governativi, sono

incommensurabilmente superiori agli aspetti negativi.

Una concessione di trent’anni per il costruttore

E’ il concessionario, quello cioè che otterrà l’affare, che avrà i

maggiori profitti dall’operazione. La gara d’appalto prevede infatti in

cambio della costruzione una concessione trentennale, che potrà essere

ridotta su accordo delle parti a vent’anni. Solo dopo questo periodo la

centrale rientrerebbe nelle mani di Montenegro e Republika Srpska (BiH).

“Ma che problema c’è se Buk-Bijela non apparterrà al Montenergo per i

prossimi trent’anni” si chiede Slobodan Vidmar, uno dei dirigenti della

compagnia elettrica montenegrina EPCG, un fervente difensore del

progetto.

In effetti in cosa consiste il problema?

Quest’ultimo consiste nel fatto che il governo da falsi argomenti

quando sostiene che il Montenegro otterrà dell’elettricità. Non sarà

così. Spetta infatti al concessionario, se vuole, non ne è obbligato,

vendere l’elettricità al Montenegro, naturalmente ai prezzi di mercato.

Il problema consiste nel fatto che qualcuno ha osato pensare di

sommergere il canyon nella Tara, ha osato offrire ad un concessionario

il più bel canyon europeo, per ottenere (forse) tra mezzo secolo

dell’energia … I rappresentanti montenegrini sostengono che il progetto

Buk-Bjiela era “nei programmi della Banca Mondiale” fin dal 1998. E’

esatto. Dopo aver rinunciato a questo progetto negli anni ’70 il

governo montenegrino ha provato a riproporlo alla Bosnia Erzegovina

negli anni ’80. Ma in quegli anni nessuno aveva avuto l’idea di cedere

lo sfruttamento della centrale ad un concessionario privato.

Oramai Montenegro e Bosnia Erzegovina hanno perso il sostegno della

Banca Mondiale. Se il progetto fosse stato realizzato alla fine degli

anni ’90 le due repubbliche ex jugoslave avrebbero probabilmente potuto

usufruire di suoi finanziamenti ed essere gli unici utilizzatori

dell’energia creata.

Perché Buk-Bijela?

“Non vi è nessuna necessità di sommergere il canyon del fiume Tara. Vi

sono altre soluzioni possibili per produrre energia elettrica” ha

dichiarato alla TV del Montenegro il professore Dusan Dragovic, da

sempre contro la costruzione di Buk-Bijela. E nessuno lo ha ancora

smentito. Al contrario. Le questioni sollevate sono: perché proprio

Buk-Bijela e non invece il completamento della centrale di Pljevlja o

una centrale elettrica sulla Moraca?

Il problema è che il governo montenegrino sta negoziando con l’entità

bosniaca della Republika Srpska. I rappresentanti del governo centrale

a Sarajevo hanno in più occasioni protestato per le azioni unilaterali

sulla questione intraprese dalla Republika Srpska e dalla compagnia

elettrica Elektroprivreda. In questo modo il Montenegro si è incuneato

in una situazione bosniaca molto complessa.

Strani legami con la società britannica EFT

Ma allora perchè il Montenegro si è immischiato in questa questione?

Nel caso in cui la società britannica EFT, che ha partecipato alla

gara d’appalto, ottenesse quest’ultimo la risposta è semplice. Il

governo montenegrino sacrifica il fiume Tara affinché, nei prossimi

decenni, EFT possa mantenere il suo monopolio sul mercato dell’energia

elettrica montenegrina.

La compagnia con sede a Londra è il principale fornitore di energia

elettrica nei Balcani ed il principale importatore per il Montenegro. I

rappresentanti governativi a Podgorica hanno numerosi ed oscuri legami

con la EFT.

A partire dal 1998, quanto il progetto Buk-Bjiela è stato rilanciato,

il consulente sull’energia del Primo ministro montenegrino, allora

Filip Vujanovic, era Vocina Lazarevic, attuale comproprietario di EFT.

Secondo alcune informazioni la compagnia EFT, oltre alla costruzione

della centrale idroelettrica, ha espresso il proprio interesse

nell’acquisto del Combinat dell’alluminio di Podgorica.

“Abbiamo il monopolio e lo conserveremo”, ha dichiarato Vuk Hamovic,

altro comproprietario di EFT. Le autorità montenegrine sembrano

intenzionate a fare tutto quanto è in loro potere perché sia

effettivamente così.

Vedi anche:

Tivat, Kotor e Budva, dove li mettiamo i rifiuti urbani?

Un convegno in Montenegro: trovare le chiavi per l’energia pulita

Montenegro: la bonifica di Punta Arza, contaminata dall’uranio

impoverito

» Fonte: © Osservatorio sui Balcani

prossimi decenni, EFT possa mantenere il suo monopolio sul mercato

dell’energia elettrica montenegrina. La compagnia con sede a Londra è

il principale fornitore di energia elettrica nei Balcani ed il

principale importatore per il Montenegro. I rappresentanti governativi

a Podgorica hanno numerosi ed oscuri legami con la EFT..." Ma si noti

anche l'effetto devastante della frammentazione della Jugoslavia

sull'approvvigionamento energetico di ciascuna di queste repubblichette

para-indipendenti: costrette oggi, nonostante le enormi risorse dei

propri territori, a litigarsi e/o spartirsi con difficolta'

opportunita' e progetti che sono nell'interesse di tutti i loro

cittadini. I quali peraltro, da entrambe le parti del "confine", sono

lo stesso popolo! E l'unica a giovarsi di questa situazione e' la

grande impresa monopolistica straniera... (I.S.)

http://auth.unimondo.org/cfdocs/obportal/

index.cfm?fuseaction=news.notizia&NewsID=3298

Montenegro : una catastrofe ambientale annunciata per il fiume Tara

Stanno per iniziare i lavori per la costruzione di una centrale

idroelettrica a Buk-Bijela, in Republika Srpska. Il progetto causerà lo

riempimento del canyon del fiume Tara in Montenergo. Perché Milo

Djukanovic si è lanciato in quest’avventura?

(10/08/2004)

Un articolo di Milka Tadic-Mijovic – Monitor

Traduzione a cura di Le Courier des Balkans

Sono state avviate le procedure per la costruzione di una centrale

idroelettrica a Buk-Bjiela e la conseguente inondazione del canyon del

fiume Tara. Il governo del Montenegro, senza aver promosso alcun

dibattito tra gli esperti in materia, e dopo negoziazioni in sordina,

ha sottoscritto l'accordo sulla costruzione congiunta della centrale

idroelettrica con la Republika Srpska. La centrale sarà costruita in un

altro stato, appunto la Bosnia Erzegovina, ma le acque del fiume Tara e

Piva inonderanno il territorio montenegrino.

Le negoziazioni sulla costruzione della centrale idroelettrica sono

state avviate da anni ma, a partire dal 1998, si sono intensificate. Il

climax della vicenda lo si raggiunge nell’aprile scorso quando in

Republika Srpska è stata convocata una gara d’appalto alla quale sono

state recapitate tre proposte per la costruzione della centrale. Solo

tra sei mesi si saprà chi avrà vinto il contratto.

Ma perché Milo Djukanovic si è lanciato in un’avventura che suscita le

forti critiche sia degli esperti che degli innamorati del fiume Tara?

Questi gli argomenti che fornisce il governo: il progetto Buk-Bijela è

il più grosso investimento che si progetta nella regione, con un costo

stimato di 300 milioni di euro; la costruzione durerà almeno cinque

anni; vi saranno occupati più di 3000 operai; ne usciranno rinnovate

tutte le infrastrutture del nord-ovest del Montenegro … e, questione

ritenuta cruciale, la centrale avrà una produzione di 450 megawatt/ora,

della quale un terzo andrà al Montenegro e contribuirà a diminuire

l’attuale deficit energetico che lo caratterizza.

I vantaggi, sottolineano i responsabili governativi, sono

incommensurabilmente superiori agli aspetti negativi.

Una concessione di trent’anni per il costruttore

E’ il concessionario, quello cioè che otterrà l’affare, che avrà i

maggiori profitti dall’operazione. La gara d’appalto prevede infatti in

cambio della costruzione una concessione trentennale, che potrà essere

ridotta su accordo delle parti a vent’anni. Solo dopo questo periodo la

centrale rientrerebbe nelle mani di Montenegro e Republika Srpska (BiH).

“Ma che problema c’è se Buk-Bijela non apparterrà al Montenergo per i

prossimi trent’anni” si chiede Slobodan Vidmar, uno dei dirigenti della

compagnia elettrica montenegrina EPCG, un fervente difensore del

progetto.

In effetti in cosa consiste il problema?

Quest’ultimo consiste nel fatto che il governo da falsi argomenti

quando sostiene che il Montenegro otterrà dell’elettricità. Non sarà

così. Spetta infatti al concessionario, se vuole, non ne è obbligato,

vendere l’elettricità al Montenegro, naturalmente ai prezzi di mercato.

Il problema consiste nel fatto che qualcuno ha osato pensare di

sommergere il canyon nella Tara, ha osato offrire ad un concessionario

il più bel canyon europeo, per ottenere (forse) tra mezzo secolo

dell’energia … I rappresentanti montenegrini sostengono che il progetto

Buk-Bjiela era “nei programmi della Banca Mondiale” fin dal 1998. E’

esatto. Dopo aver rinunciato a questo progetto negli anni ’70 il

governo montenegrino ha provato a riproporlo alla Bosnia Erzegovina

negli anni ’80. Ma in quegli anni nessuno aveva avuto l’idea di cedere

lo sfruttamento della centrale ad un concessionario privato.

Oramai Montenegro e Bosnia Erzegovina hanno perso il sostegno della

Banca Mondiale. Se il progetto fosse stato realizzato alla fine degli

anni ’90 le due repubbliche ex jugoslave avrebbero probabilmente potuto

usufruire di suoi finanziamenti ed essere gli unici utilizzatori

dell’energia creata.

Perché Buk-Bijela?

“Non vi è nessuna necessità di sommergere il canyon del fiume Tara. Vi

sono altre soluzioni possibili per produrre energia elettrica” ha

dichiarato alla TV del Montenegro il professore Dusan Dragovic, da

sempre contro la costruzione di Buk-Bijela. E nessuno lo ha ancora

smentito. Al contrario. Le questioni sollevate sono: perché proprio

Buk-Bijela e non invece il completamento della centrale di Pljevlja o

una centrale elettrica sulla Moraca?

Il problema è che il governo montenegrino sta negoziando con l’entità

bosniaca della Republika Srpska. I rappresentanti del governo centrale

a Sarajevo hanno in più occasioni protestato per le azioni unilaterali

sulla questione intraprese dalla Republika Srpska e dalla compagnia

elettrica Elektroprivreda. In questo modo il Montenegro si è incuneato

in una situazione bosniaca molto complessa.

Strani legami con la società britannica EFT

Ma allora perchè il Montenegro si è immischiato in questa questione?

Nel caso in cui la società britannica EFT, che ha partecipato alla

gara d’appalto, ottenesse quest’ultimo la risposta è semplice. Il

governo montenegrino sacrifica il fiume Tara affinché, nei prossimi

decenni, EFT possa mantenere il suo monopolio sul mercato dell’energia

elettrica montenegrina.

La compagnia con sede a Londra è il principale fornitore di energia

elettrica nei Balcani ed il principale importatore per il Montenegro. I

rappresentanti governativi a Podgorica hanno numerosi ed oscuri legami

con la EFT.

A partire dal 1998, quanto il progetto Buk-Bjiela è stato rilanciato,

il consulente sull’energia del Primo ministro montenegrino, allora

Filip Vujanovic, era Vocina Lazarevic, attuale comproprietario di EFT.

Secondo alcune informazioni la compagnia EFT, oltre alla costruzione

della centrale idroelettrica, ha espresso il proprio interesse

nell’acquisto del Combinat dell’alluminio di Podgorica.

“Abbiamo il monopolio e lo conserveremo”, ha dichiarato Vuk Hamovic,

altro comproprietario di EFT. Le autorità montenegrine sembrano

intenzionate a fare tutto quanto è in loro potere perché sia

effettivamente così.

Vedi anche:

Tivat, Kotor e Budva, dove li mettiamo i rifiuti urbani?

Un convegno in Montenegro: trovare le chiavi per l’energia pulita

Montenegro: la bonifica di Punta Arza, contaminata dall’uranio

impoverito

» Fonte: © Osservatorio sui Balcani

http://komunist.free.fr/arhiva/jun2004/nostalgija.html

Arhiva : : Jun 2004.

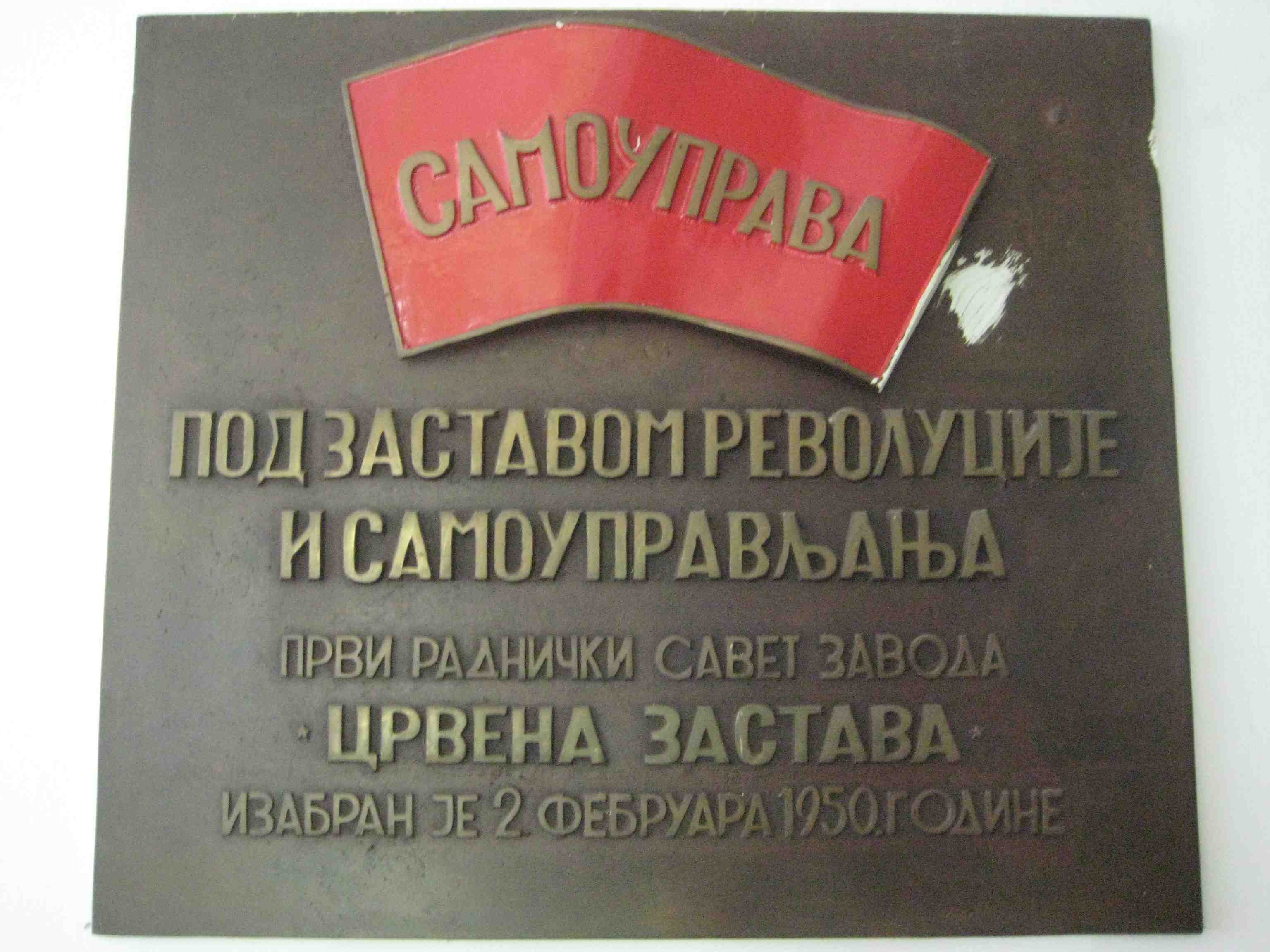

Nostalgija za Titovim izgubljenim svetom

Društvena i ekonomska nestabilnost navodi mnoge građane na Balkanu da

se s nostalgijom prisećaju Titovog doba.

Pišu: Markus Taner, Muhamet Hajrulahu iz Prištine, Drago Hedl iz

Osijeka, Dino Bajramović iz Sarajeva, Mitko Jovanov iz Skoplja,

Vladimir Sudar iz Beograda i Tanja Matić iz Subotice (BCR Br 500,

28-maj-04)

Kaćuša Jašari, predsednica Socijaldemokratske partije Kosova, ima lepe

uspomene na dane kada je nosila štafetu za pokojnog jugoslovenskog

predsednika Josipa Broza Tita.

Kao istaknuti albanski političar u komunističkom režimu, ona je imala

tu čast da nosi štafetu sa porukom omladine bivše Jugoslavije za

predsednika koja je prošla kroz čitavu zemlju – od Slovenije na severu

do Kosova i Makedonije na jugu.

Vrhunac je bilo uručivanje štafete predsedniku na prepunom stadionu

Jugoslovenske narodne armije, JNA, u Beogradu na njegov rođendan 25.

maja. "Proslava Titovog rođendana se savršeno slagala sa obrazovanjem

koje smo sticali u to vreme", priseća se Jašarijeva. "Bila je to

proslava za sve – praznik mladosti."

Stavovi Jašarijeve o Danu mladosti nisu toliko neobični kako bi to

mnogi pomislili. Mada su četiri od šest bivših jugoslovenskih republika

postale nezavisne države, a Kosovo – koje je još uvek deo Srbije –

očajnički želi da stekne nezavisnost, mnogi stanovnici bivše

federacije, pogotovo oni stariji i sa siromašnijeg juga, prisećaju se

Jugoslavije sa nostalgijom.

Za njih je to bilo vreme kada je hrane i posla bilo u izobilju, kada je

stopa kriminaliteta bila niska, kada etničke razlike nisu bile bitne, a

teške političke odluke su prepuštane maršalu Titu, čiji je ozbiljan lik

posmatrao svet sa hiljada portreta okačenih u kancelarijama,

železničkim stanicama, prodavnicama i privatnim kućama.

"U Titovo vreme sam bio bogat. Bilo je fabrika i zanatskih radnji –

imali smo posla, imali smo sve", priseća se 84-godišnji Mehdi Šabani iz

Prištine. "Životni standard je bio znatno bolji", dodaje Osman

Krasnići, star 62 godine, takođe stanovnik glavnog grada Kosova. "Sa

tadašnjom malom platom ste mogli da izgradite sebi kuću – danas to ne

možete da uradite."

Kosovo je bilo najmanje jugoslovensko iz prostog razloga što je bilo

najmanje slovensko. "Albanci su bili manje vezani za Jugoslaviju u

odnosu na druge narode jer jedini nisu bili Sloveni. Sve što nam je

bilo zajedničko bila je komunistička ideologija, koja je bila manje

lična nego što bi to bio zajednički jezik, kultura i vera", kaže

Jašarijeva.

Među susednim Slovenima u Makedoniji, gde su stanovnici dobili ne samo

radna mesta i hranu već i svoju republiku, naklonost prema Titu je

znatno jača. Mada je sveprisutno Titovo ime uklonjeno sa većine ulice i

trgova u bivšoj Jugoslaviji, u makedonskoj prestonici, u Skoplju,

najveća i najelitnija škola još uvek nosi naziv "Josip Broz Tito", a

svakoga 25. maja mu odaje poštu folklornim plesom i buketima cveća.

Za mnoge Makedonce se nezavisnost opterećena siromaštvom pokazala kao

lošom zamenom za lagodniji život u velikoj slovenskoj federaciji. "Nije

bilo podele na bogate i siromašne, svako je mogao priuštiti sebi da ide

u školu, da ima sopstveni dom i posao", tvrdi Makedonka Jančevska,

stara 62 godine, učiteljica makedonskog jezika u penziji.

"Patriotizam se podsticao na jednoj široj osnovi; to je tada značilo

poštovanje specifičnosti svih nacionalnosti koje su činile Jugoslaviju."

"Životni standard koji smo imali pružao nam je ekonomsku sigurnost i

mnoge socijalne beneficije", priseća se Petar Mojsov, star 46 godina,

računovođa iz Makedonije. "Svako je mogao da priušti sebi stan i kola.

Putovao sam u Italiju u kupovinu. Išao sam u Grčku kad god bih to

poželeo."

Toše Načkov, električar, seća se kada bi čitavo stanovništvo gradova u

Makedoniji izašlo na ulice da pozdravi rođendansku štafetu koje su

omladinci poput Kaćuše Jašari sa Kosova nekada ponosno nosili.

"Nestrpljivo smo iščekivali dan kada bi štafeta trebalo da stigne u naš

grad", kaže Načkov. "To je bilo poput praznika, a svi mi bi se okupili

na trgu da je dočekamo i ispratimo na put u susedni grad."

Uspomene na Tita su tako jake u Makedonije da je prošle godine Slobodan

Ugrinovski osnovao novo udruženje za proslavljanje i čuvanje uspomene

na njegov život. Oko 6.180 članova ovog udruženja odlazi na putovanja

radi posete (nekolicini) institucija koje još uvek nose Titovo ime, te

da bi obišli najvažnija mesta – Titov grob u beogradskoj Kući cveća i

njegovo rodno selo Kumrovec u Hrvatskoj.

Kao i Makedonci, nesrećni stanovnici ratom opustošene, ekonomski

ruinirane Bosne i Hercegovine ne mogu odoleti, a da ne uporede život

pod Titom sa onim što imaju sada. Titovo ime, po pravilu, Bosance

asocira na "dobra stara vremena".

Kult Josipa Broza Tita ne bledi. Štaviše, sve je snažniji. Kada su

vlasti nedavno pokušale da preimenuju glavnu ulicu u Sarajevu u Ulicu

Alije Izetbegovića, prvog bosanskog predsednika u nezavisnoj državi,

Sarajlije su krenule u akciju, postavljajući bilbord nasred bulevara sa

Titovom slikom i sloganom "Ovo je Ulica Maršala Tita". Više meseci

nakon što je inicijativa propala, ovaj bilbord je još uvek na istom

mestu.

"Mladi se okreću Titu jer on personifikuje prosperitet", kaze Adnan

Korić, član bosanskog udruženja posvećenog uspomeni na Josipa Broza

Tita. "Oni znaju da smo samo u Titovo vreme neprestano napredovali

čitavih 45 godina u svakoj oblasti društvenog i ekonomskog života."

Korić veruje da Bosanci žude za vremenom kada im nisu bile potrebne

različite valute i vize da bi se kretali područjem koje je nekada bilo

jedinstvena teritorija. "Sada ne možete da potrošite pun rezervoar

benzina vozeći u jednom smeru, a da prethodno ne pribavite šest viza",

šali se Korić.

U Sarajevu se Titov lik vratio iz podruma i prodavnica polovne robe u

popularne barove i restorane. U baru koji se zove "Tito", popularnom

studentskom sastajalištu, zidovi su prekriveni predmetima i

fotografijama iz Titovog vremena dok konobari nose uniforme sa još uvek

prepoznatljivim Titovim potpisom. "Dolazim ovde da razmišljam i živim u

prošlosti", kaže 26-godišnji Amel. "Ma šta neki govorili, naša prošlost

je bila svetlija od naše budućnosti."

Dok su Bosna i Makedonija izgubile puno, a stekle malo od raspada

Titove Jugoslavije, uspomene su nešto manje ružičaste u susednoj Srbiji

i Hrvatskoj. Za vreme vladavine Slobodana Miloševića, duže od jedne

decenije, Tito je u Srbiji demonizovan kao hrvatski neprijatelj koji je

doprineo srpskom slomu u bivšoj Jugoslaviji.

Međutim, čak i u Srbiji, razočarenja iz prošle decenije, uključujući

izgubljene ratove i sunovrat životnog standarda, navelo je mnoge da

promene mišljenje. Miša Đurković iz beogradskog Instituta za evropske

studije kaže da sve snažnija nostalgija za Titovim vremenom ne

proističe samo iz žala za dobrim životnim standardom.

"Čežnja za [starom Jugoslavijom] je takođe žudnja za redom i

dostojanstvom", kaže on. "Naša 'mekana' komunistička diktatura je,

ipak, predstavljala dobro utemeljen sistem u kome nije bilo pljački,

haosa i anarhije koji su sada uobičajeni, što je žalosno."

Đurković veruje da se ova vrsta nostalgije proširila i na mlađe

generacije. "Mladi danas u jugonostalgiji vide instrument protesta

protiv trulog zaveštanja devedesetih koje su nasledili."

Svakako, ne postoje naznake da će Kuća cveća zatvoriti svoja vrata

hodočasnicima, mada se ovom mestu posvećuje manje pažnje i brige nego

što je to bio slučaj u osamdesetim, kada su inostrane diplomate i

šefovi država redovno dolazili na Titov grob da odaju poštu.

Iako krunisane glave i predsednici država više ne prolaze pored Titovog

mauzoleja, ratni veterani, članovi komunističkih partija i nevladinih

organizacija se iznova uvek vraćaju na rođendan pokojnog predsednika.

Svetlana Ognjanović, portparol Kuće cveća, rekla je da očekuje do 2.000

ljudi za ovogodišnju komemoraciju, uključujući veliku grupu slovenačkih

"Anđela pakla" (slovenački motociklisti redovno posećuju Titov grob

svake godine još od 2000.).

Predsednik nevladine organizacije "Centar Tito", penzionisani armijski

general Stevan Mirković takođe obeležava Dan mladosti večerom na kojoj

se služi vojnički pasulj, a najstarijem članu, samom Mirkoviću, će

jedan omladinac i jedna omladinka uručiti štafetu mladosti. A na

krajnjem severu Srbije, Blaško Gabrić, je otišao najdalje, koliko se

god moglo, u svojoj kampanji da obnovi uspomenu na Tita, otvarajući

tematski park pod imenom "Jugolend" ("Yugoland") u blizini pograničnog

grada, Subotice.

Mini-Jugoslavija ima nekoliko geografskih atributa bivše Jugoslavije,

uključujući brdo nazvano po najvišem planinskom vrhu Triglavu u

Sloveniji. Stare zastave sa crvenom zvezdom se vijore pored ulaza, a

Titove slike se nalaze na svakom zidu prikazujući ga kako lovi, svira

klavir, čita, pleše i u poseti stranim državama. Blaško čak izdaje

dokumenta o državljanstvu za Jugolend, i do sada ih ima 2.500.

Blaško kaže da je ukidanje imena "Jugoslavija" – zločin. "Vlada [Srbije

i Crne Gore] je ubila ime najbolje zemlje – Jugoslavije, što je

poslednja stvar koja nas je podsećala na bivšu Jugoslaviju, ne pitajući

ljude za njihov pristanak", kaže on. "Ja sam morao da ga sačuvam za sve

jugonostalgičare koji mogu da dođu ovde i uživaju u uspomenama na

Titovo vreme."

Mada Gabrić tvrdi da su posetioci svih starosnih uzrasta, fotografije

sa proslava održanih u Jugolendu ukazuju da je jugonostalgija fenomen

koji se pretežno odnosi na sredovečne i starije ljude.

Među mladim ljudima iz svih republika, interes za Tita je mali ili je

ograničen na ironični kult poput bivših istočnih Nemaca koji s ironijom

proslavljaju svoju komunističku prošlost vozeći trabante i noseći

bedževe sa komunističkim sloganima.

Aca Bogdanović, star 32 godine, iz Beograda, je rekao da Tita poštuje

"jer je bio najveći hedonista dvadesetog veka" – što teško da je vrsta

komplimenta koji bi pravi privrženici cenili. Ova vrsta ironične ocene

je jednako upadljiva u Titovoj matičnoj republici – Hrvatskoj, gde je

ostalo malo onih koji su verni njegovim političkim idejama, dok znatno

brojniji mlađi ljudi uživaju eksperimentišući sa titoističkim motivima.

"Uglavnom mladi kupuju ove majice – oni koji nisu čak ni bili rođeni

kada je Tito umro!" primećuje prodavac iz Osijeka, na severoistoku

Hrvatske, pokazujući na gomilu majica sa Titovim likom.

Mada se uglavnom neki stariji ljudi mogu uistinu opisati kao pravi

jugonostalgičari, smatra zagrebački sociolog Dražen Lalić, sve veći

interes za Tita lično i za zemlju kojom je nekada vladao proističe iz

činjenice da Hrvatska sada ima opušteniji odnos prema svojoj državnosti

nego što je to bio slučaj pre deset godina.

"Nakon što smo godinama slušali da mi isključivo pripadamo

mediteranskoj i centralnoevropskoj kulturi, sada se suočavamo sa

činjenicom da Hrvatska takođe pripada balkanskom kulturnom krugu", kaže

Lalić.

"Jugonostalgija postoji, ali ljudi ne žale za Jugoslavijom kao svojom

bivšom državom", kaže Milanka Opačić iz Socijaldemokratske partije.

"Oni žale za kvalitetom života koji su tada imali. Smatraju da im je

bilo znatno bolje, da su bili bezbedniji, da su imali bolji životni

standard i bolju zdravstvenu zaštitu nego što je to sada slučaj."

Prosta je činjenica da jugonostalgija više ne izaziva antagonizam jer

niko ozbiljno ne veruje da će Jugoslavija ponovo biti uspostavljena. U

Hrvatskoj, dok zemlja grabi ka Evropskoj uniji, Jugoslavija se smatra

delom prošlosti – neuspešnim projektom koji se ne može i neće

restaurirati. Usled toga, jugonostalgičari se u Hrvatskoj sada pre

smatraju romantičarima nego neprijateljima države, kako su nekad

nazivani za vreme vladavine hrvatskog nacionalističkog lidera Franje

Tuđmana.

(This article originally appeared in Balkan Crisis Report, produced by

the Institute for War and Peace Reporting, www.iwpr.net)

Arhiva : : Jun 2004.

Nostalgija za Titovim izgubljenim svetom

Društvena i ekonomska nestabilnost navodi mnoge građane na Balkanu da

se s nostalgijom prisećaju Titovog doba.

Pišu: Markus Taner, Muhamet Hajrulahu iz Prištine, Drago Hedl iz

Osijeka, Dino Bajramović iz Sarajeva, Mitko Jovanov iz Skoplja,

Vladimir Sudar iz Beograda i Tanja Matić iz Subotice (BCR Br 500,

28-maj-04)

Kaćuša Jašari, predsednica Socijaldemokratske partije Kosova, ima lepe

uspomene na dane kada je nosila štafetu za pokojnog jugoslovenskog

predsednika Josipa Broza Tita.

Kao istaknuti albanski političar u komunističkom režimu, ona je imala

tu čast da nosi štafetu sa porukom omladine bivše Jugoslavije za

predsednika koja je prošla kroz čitavu zemlju – od Slovenije na severu

do Kosova i Makedonije na jugu.

Vrhunac je bilo uručivanje štafete predsedniku na prepunom stadionu

Jugoslovenske narodne armije, JNA, u Beogradu na njegov rođendan 25.

maja. "Proslava Titovog rođendana se savršeno slagala sa obrazovanjem

koje smo sticali u to vreme", priseća se Jašarijeva. "Bila je to

proslava za sve – praznik mladosti."

Stavovi Jašarijeve o Danu mladosti nisu toliko neobični kako bi to

mnogi pomislili. Mada su četiri od šest bivših jugoslovenskih republika

postale nezavisne države, a Kosovo – koje je još uvek deo Srbije –

očajnički želi da stekne nezavisnost, mnogi stanovnici bivše

federacije, pogotovo oni stariji i sa siromašnijeg juga, prisećaju se

Jugoslavije sa nostalgijom.

Za njih je to bilo vreme kada je hrane i posla bilo u izobilju, kada je

stopa kriminaliteta bila niska, kada etničke razlike nisu bile bitne, a

teške političke odluke su prepuštane maršalu Titu, čiji je ozbiljan lik

posmatrao svet sa hiljada portreta okačenih u kancelarijama,

železničkim stanicama, prodavnicama i privatnim kućama.

"U Titovo vreme sam bio bogat. Bilo je fabrika i zanatskih radnji –

imali smo posla, imali smo sve", priseća se 84-godišnji Mehdi Šabani iz

Prištine. "Životni standard je bio znatno bolji", dodaje Osman

Krasnići, star 62 godine, takođe stanovnik glavnog grada Kosova. "Sa

tadašnjom malom platom ste mogli da izgradite sebi kuću – danas to ne

možete da uradite."

Kosovo je bilo najmanje jugoslovensko iz prostog razloga što je bilo

najmanje slovensko. "Albanci su bili manje vezani za Jugoslaviju u

odnosu na druge narode jer jedini nisu bili Sloveni. Sve što nam je

bilo zajedničko bila je komunistička ideologija, koja je bila manje

lična nego što bi to bio zajednički jezik, kultura i vera", kaže

Jašarijeva.

Među susednim Slovenima u Makedoniji, gde su stanovnici dobili ne samo

radna mesta i hranu već i svoju republiku, naklonost prema Titu je

znatno jača. Mada je sveprisutno Titovo ime uklonjeno sa većine ulice i

trgova u bivšoj Jugoslaviji, u makedonskoj prestonici, u Skoplju,

najveća i najelitnija škola još uvek nosi naziv "Josip Broz Tito", a

svakoga 25. maja mu odaje poštu folklornim plesom i buketima cveća.

Za mnoge Makedonce se nezavisnost opterećena siromaštvom pokazala kao

lošom zamenom za lagodniji život u velikoj slovenskoj federaciji. "Nije

bilo podele na bogate i siromašne, svako je mogao priuštiti sebi da ide

u školu, da ima sopstveni dom i posao", tvrdi Makedonka Jančevska,

stara 62 godine, učiteljica makedonskog jezika u penziji.

"Patriotizam se podsticao na jednoj široj osnovi; to je tada značilo

poštovanje specifičnosti svih nacionalnosti koje su činile Jugoslaviju."

"Životni standard koji smo imali pružao nam je ekonomsku sigurnost i

mnoge socijalne beneficije", priseća se Petar Mojsov, star 46 godina,

računovođa iz Makedonije. "Svako je mogao da priušti sebi stan i kola.

Putovao sam u Italiju u kupovinu. Išao sam u Grčku kad god bih to

poželeo."

Toše Načkov, električar, seća se kada bi čitavo stanovništvo gradova u

Makedoniji izašlo na ulice da pozdravi rođendansku štafetu koje su

omladinci poput Kaćuše Jašari sa Kosova nekada ponosno nosili.

"Nestrpljivo smo iščekivali dan kada bi štafeta trebalo da stigne u naš

grad", kaže Načkov. "To je bilo poput praznika, a svi mi bi se okupili

na trgu da je dočekamo i ispratimo na put u susedni grad."

Uspomene na Tita su tako jake u Makedonije da je prošle godine Slobodan

Ugrinovski osnovao novo udruženje za proslavljanje i čuvanje uspomene

na njegov život. Oko 6.180 članova ovog udruženja odlazi na putovanja

radi posete (nekolicini) institucija koje još uvek nose Titovo ime, te

da bi obišli najvažnija mesta – Titov grob u beogradskoj Kući cveća i

njegovo rodno selo Kumrovec u Hrvatskoj.

Kao i Makedonci, nesrećni stanovnici ratom opustošene, ekonomski

ruinirane Bosne i Hercegovine ne mogu odoleti, a da ne uporede život

pod Titom sa onim što imaju sada. Titovo ime, po pravilu, Bosance

asocira na "dobra stara vremena".

Kult Josipa Broza Tita ne bledi. Štaviše, sve je snažniji. Kada su

vlasti nedavno pokušale da preimenuju glavnu ulicu u Sarajevu u Ulicu

Alije Izetbegovića, prvog bosanskog predsednika u nezavisnoj državi,

Sarajlije su krenule u akciju, postavljajući bilbord nasred bulevara sa

Titovom slikom i sloganom "Ovo je Ulica Maršala Tita". Više meseci

nakon što je inicijativa propala, ovaj bilbord je još uvek na istom

mestu.

"Mladi se okreću Titu jer on personifikuje prosperitet", kaze Adnan

Korić, član bosanskog udruženja posvećenog uspomeni na Josipa Broza

Tita. "Oni znaju da smo samo u Titovo vreme neprestano napredovali

čitavih 45 godina u svakoj oblasti društvenog i ekonomskog života."

Korić veruje da Bosanci žude za vremenom kada im nisu bile potrebne

različite valute i vize da bi se kretali područjem koje je nekada bilo

jedinstvena teritorija. "Sada ne možete da potrošite pun rezervoar

benzina vozeći u jednom smeru, a da prethodno ne pribavite šest viza",

šali se Korić.

U Sarajevu se Titov lik vratio iz podruma i prodavnica polovne robe u

popularne barove i restorane. U baru koji se zove "Tito", popularnom

studentskom sastajalištu, zidovi su prekriveni predmetima i

fotografijama iz Titovog vremena dok konobari nose uniforme sa još uvek

prepoznatljivim Titovim potpisom. "Dolazim ovde da razmišljam i živim u

prošlosti", kaže 26-godišnji Amel. "Ma šta neki govorili, naša prošlost

je bila svetlija od naše budućnosti."

Dok su Bosna i Makedonija izgubile puno, a stekle malo od raspada

Titove Jugoslavije, uspomene su nešto manje ružičaste u susednoj Srbiji

i Hrvatskoj. Za vreme vladavine Slobodana Miloševića, duže od jedne

decenije, Tito je u Srbiji demonizovan kao hrvatski neprijatelj koji je

doprineo srpskom slomu u bivšoj Jugoslaviji.

Međutim, čak i u Srbiji, razočarenja iz prošle decenije, uključujući

izgubljene ratove i sunovrat životnog standarda, navelo je mnoge da

promene mišljenje. Miša Đurković iz beogradskog Instituta za evropske

studije kaže da sve snažnija nostalgija za Titovim vremenom ne

proističe samo iz žala za dobrim životnim standardom.

"Čežnja za [starom Jugoslavijom] je takođe žudnja za redom i

dostojanstvom", kaže on. "Naša 'mekana' komunistička diktatura je,

ipak, predstavljala dobro utemeljen sistem u kome nije bilo pljački,

haosa i anarhije koji su sada uobičajeni, što je žalosno."

Đurković veruje da se ova vrsta nostalgije proširila i na mlađe

generacije. "Mladi danas u jugonostalgiji vide instrument protesta

protiv trulog zaveštanja devedesetih koje su nasledili."

Svakako, ne postoje naznake da će Kuća cveća zatvoriti svoja vrata

hodočasnicima, mada se ovom mestu posvećuje manje pažnje i brige nego

što je to bio slučaj u osamdesetim, kada su inostrane diplomate i

šefovi država redovno dolazili na Titov grob da odaju poštu.

Iako krunisane glave i predsednici država više ne prolaze pored Titovog

mauzoleja, ratni veterani, članovi komunističkih partija i nevladinih

organizacija se iznova uvek vraćaju na rođendan pokojnog predsednika.

Svetlana Ognjanović, portparol Kuće cveća, rekla je da očekuje do 2.000

ljudi za ovogodišnju komemoraciju, uključujući veliku grupu slovenačkih

"Anđela pakla" (slovenački motociklisti redovno posećuju Titov grob

svake godine još od 2000.).

Predsednik nevladine organizacije "Centar Tito", penzionisani armijski

general Stevan Mirković takođe obeležava Dan mladosti večerom na kojoj

se služi vojnički pasulj, a najstarijem članu, samom Mirkoviću, će

jedan omladinac i jedna omladinka uručiti štafetu mladosti. A na

krajnjem severu Srbije, Blaško Gabrić, je otišao najdalje, koliko se

god moglo, u svojoj kampanji da obnovi uspomenu na Tita, otvarajući

tematski park pod imenom "Jugolend" ("Yugoland") u blizini pograničnog

grada, Subotice.

Mini-Jugoslavija ima nekoliko geografskih atributa bivše Jugoslavije,

uključujući brdo nazvano po najvišem planinskom vrhu Triglavu u

Sloveniji. Stare zastave sa crvenom zvezdom se vijore pored ulaza, a

Titove slike se nalaze na svakom zidu prikazujući ga kako lovi, svira

klavir, čita, pleše i u poseti stranim državama. Blaško čak izdaje

dokumenta o državljanstvu za Jugolend, i do sada ih ima 2.500.

Blaško kaže da je ukidanje imena "Jugoslavija" – zločin. "Vlada [Srbije

i Crne Gore] je ubila ime najbolje zemlje – Jugoslavije, što je

poslednja stvar koja nas je podsećala na bivšu Jugoslaviju, ne pitajući

ljude za njihov pristanak", kaže on. "Ja sam morao da ga sačuvam za sve

jugonostalgičare koji mogu da dođu ovde i uživaju u uspomenama na

Titovo vreme."

Mada Gabrić tvrdi da su posetioci svih starosnih uzrasta, fotografije

sa proslava održanih u Jugolendu ukazuju da je jugonostalgija fenomen

koji se pretežno odnosi na sredovečne i starije ljude.

Među mladim ljudima iz svih republika, interes za Tita je mali ili je

ograničen na ironični kult poput bivših istočnih Nemaca koji s ironijom

proslavljaju svoju komunističku prošlost vozeći trabante i noseći

bedževe sa komunističkim sloganima.

Aca Bogdanović, star 32 godine, iz Beograda, je rekao da Tita poštuje

"jer je bio najveći hedonista dvadesetog veka" – što teško da je vrsta

komplimenta koji bi pravi privrženici cenili. Ova vrsta ironične ocene

je jednako upadljiva u Titovoj matičnoj republici – Hrvatskoj, gde je

ostalo malo onih koji su verni njegovim političkim idejama, dok znatno

brojniji mlađi ljudi uživaju eksperimentišući sa titoističkim motivima.

"Uglavnom mladi kupuju ove majice – oni koji nisu čak ni bili rođeni

kada je Tito umro!" primećuje prodavac iz Osijeka, na severoistoku

Hrvatske, pokazujući na gomilu majica sa Titovim likom.

Mada se uglavnom neki stariji ljudi mogu uistinu opisati kao pravi

jugonostalgičari, smatra zagrebački sociolog Dražen Lalić, sve veći

interes za Tita lično i za zemlju kojom je nekada vladao proističe iz

činjenice da Hrvatska sada ima opušteniji odnos prema svojoj državnosti

nego što je to bio slučaj pre deset godina.

"Nakon što smo godinama slušali da mi isključivo pripadamo

mediteranskoj i centralnoevropskoj kulturi, sada se suočavamo sa

činjenicom da Hrvatska takođe pripada balkanskom kulturnom krugu", kaže

Lalić.

"Jugonostalgija postoji, ali ljudi ne žale za Jugoslavijom kao svojom

bivšom državom", kaže Milanka Opačić iz Socijaldemokratske partije.

"Oni žale za kvalitetom života koji su tada imali. Smatraju da im je

bilo znatno bolje, da su bili bezbedniji, da su imali bolji životni

standard i bolju zdravstvenu zaštitu nego što je to sada slučaj."

Prosta je činjenica da jugonostalgija više ne izaziva antagonizam jer

niko ozbiljno ne veruje da će Jugoslavija ponovo biti uspostavljena. U

Hrvatskoj, dok zemlja grabi ka Evropskoj uniji, Jugoslavija se smatra

delom prošlosti – neuspešnim projektom koji se ne može i neće

restaurirati. Usled toga, jugonostalgičari se u Hrvatskoj sada pre

smatraju romantičarima nego neprijateljima države, kako su nekad

nazivani za vreme vladavine hrvatskog nacionalističkog lidera Franje

Tuđmana.

(This article originally appeared in Balkan Crisis Report, produced by

the Institute for War and Peace Reporting, www.iwpr.net)

(english / francais / italiano)

Regressione culturale su tutti i fronti

La guerra di questi anni contro la Jugoslavia e contro il socialismo,

mirata al ristabilimento dell'"ancien regime" nei Balcani, e' stata

accompagnata e sostenuta da una totale regressione culturale. Questo e'

palese in Kosovo e fra gli albanesi come d'altronde anche in tutte le

altre repubbliche ex-federate e tra tutte le altre componenti

nazionalitarie.

1. Sul ritorno della vendetta di sangue ("faide"):

- Résurgence des crimes d’honneur au Kosovo ("Le Courrier des Balkans"

/ IWPR)

- ALBANIA: DURO CODICE VENDETTA NON RISPARMIA PACIFICATORE (ANSA)

2. Sullo sfascio del sistema sanitario ed il risorgere delle

superstizioni:

- DESPERATE ALBANIANS PLACE FAITH IN OLD-TIME HEALERS (Jeton Musliu /

IWPR)

3. Sul massiccio abbandono della scuola dell'obbligo e sul repentino

arretramento della condizione femminile:

- GIRLS FACE PRESSURE TO STOP "WASTING TIME" IN SCHOOL (Zana Limani and

Driton Maliqi / IWPR)

=== 1 ===

( The original text in english:

"Blood Feuds Revive in Unstable Kosovo. Rise in “Honour killings”

blamed on collapse of respect for law and order."

By Fatos Bytyci in Gjakova (BCR No 481, 19-Feb-04)

http://www.iwpr.net/index.pl?archive/bcr3/bcr3_200402_481_4_eng.txt )

http://www.balkans.eu.org/article4117.html

Résurgence des crimes d’honneur au Kosovo

TRADUIT PAR PIERRE DÉRENS

Publié dans la presse : 19 février 2004

Mise en ligne : samedi 21 février 2004

Le nombre des « crimes d’honneur » ne cesse d’augmenter au Kosovo. Dans

les années 1990, une vaste campagne de réconciliation avait été lancée,

mais depuis 1999, la faillite du système judiciaire justifie le recours

à la vendetta traditionnelle.

Par Fatos Bytyci

Il n’y a aucun signe de vie à l’extérieur de la maison des Murati, dans

le village de Duzhnje, au sud-ouest du Kosovo. Les fenêtres sont

fermées et il n’y a pas de traces de pas dans la neige devant la maison.

Osman Murati, soixante ans, n’ouvre le portail central que pour sortir

la tête et voir qui frappe. Il a peur que des gens ne viennent lui

tirer dessus, pour venger le double crime que vient de commettre Valon,

son fils de 20 ans.

Les crimes d’honneur sont profondément enracinés dans la culture

albanaise et ont été formellement reconnus dans la collection des lois

tribales du Moyen Age, connue sous le nom du Kanun de Lekë Dukagjini.

Ce dernier précise que « si un homme en tue un autre, il faut qu’un

autre homme de la famille de la victime, rende la pareille ».

Sous l’ère communiste, les crimes de sang étaient relativement rares

chez les Albanais du Kosovo ou d’Albanie. Mais après les temps troublés

des années 1990, les principes du kanun de Lekë sont réapparus, d’abord

dans le chaos de l’Albanie post-communiste, puis dans le Kosovo voisin,

surtout après les frappes de l’OTAN et le retrait des forces serbes.

Pendant plus de trois mois, ni Valon Murati, ni son frère, son père et

son grand-père n’ont bougé de chez eux, par peur de la vendetta.

Les assassinats ont eu lieu le 10 novembre quand Valon Murati, membre

de la police du Kosovo (KPS) à Gjakova (Djakovica), a tué Sadik et

Safedin Zeneli, âgés respectivement de 55 et 30 ans, en rentrant chez

lui. Les victimes étaient cousins de Valon et venaient du même village.

Isak Zeneli a entendu les coups de feu. « J’ai vu deux personnes

allongées par terre », se souvient-il. « Valon courait vers le village

en criant : J’ai tué deux personnes ».

En attendant son procès, Valon Murati a été libéré sous caution. La

famille Zeneli est furieuse et croit que l’assassin a été relâché parce

qu’il s’agissait d’un officier du KPS. Maintenant ils menacent de se

faire justice eux-mêmes. Sadik Dobruna, leur avocat, affirme que le

tribunal a agi sans raison. « Cette décision a mis le suspect en

danger. Elle lui fera plus de mal que de bien ».

Faillite de la justice

Xhafer Zeneli, le frère de Sadik, n’a pas écarté la menace que la

famille ne prenne sa revanche sur Valon Murati. « Il n’y a pas de

justice au Kosovo. Il a tué mon frère et il est libre. Sadik a beaucoup

de fils en Allemagne. À leur retour, ils se vengeront ».

Selon le canon de Lekë Dukagjini, il faut qu’un meurtrier demande sa

sécurité à la famille de la victime - qui doit donner sa parole, sa «

besa » - pour ne pas être abattu en sortant de chez lui.

Dans le cas des Murati, la famille des morts a refusé de se plier à ce

code, laissant ainsi les hommes de la famille Murati se demander s’ils

n’allaient pas être les victimes d’une vendetta.

C’est précisément ce que craint Valon. En apparaissant à sa porte, il a

insisté pour dire qu’il avait tué les deux hommes pour se défendre, et

il a supplié les Zeleni de comprendre. « Comment les persuader que

j’étais attaqué et que je n’ai fait que me défendre ? »

Depuis la fin de la guerre au Kosovo, en juin 1999, jusqu’à la fin de

l’année 2003, le Kosovo a enregistré quelque quarante meurtres de sang,

selon le Conseil pour la Défense des Droits de l’Homme et des Libertés

de Pristina (KLMDNJ).

« Des cas de vengeance pour meurtre réapparaissent en conséquence du

faible fonctionnement de la loi et des institutions chargées

d’appliquer les lois », précise Pajazit Nushi, président de ce Conseil.

Des experts locaux mettent en cause le vide légal et politique qui

prévaut depuis 1999, quand l’administration serbe s’est retirée du

Kosovo, et que la communauté internationale n’a pas voulu remettre les

clés du pouvoir aux institutions albanaises du Kosovo qui auraient pu

revendiquer leur indépendance. Le système juridique lui-même, y compris

les juges, les procureurs et la police, est largement aussi corrompu et

ouvert à toute intimidation.

Les assassinats ne sont pas punis, et beaucoup de gens estiment que ni

la loi ni les tribunaux méritent d’être respectés. En novembre 2002, la

radio-télévision du Kosovo a retransmis une émission policière où un

père dont le fils avait été tué annonçait que si les assassins

n’étaient pas punis, « nous résoudrions le problème sans l’aide de la

police ».

Dans les années 1990, Anton Cetta avait lancé une campagne de

réconciliation

De 1990 à 1997, des centaines de familles impliquées dans des crimes de

sang, se sont réconciliées grâce à une campagne de masse lancée par le

regretté Anton Cetta, professeur à la retraite de l’Université de

Pristina. Ce dernier avait fait le tour de centaines de villages,

convainquant des hommes d’oublier leurs querelles de famille et

d’organiser des cérémonies de réconciliation, autour de festins, de

musique et de danse.

La tâche fut rude. Un jour, le professeur avait confié : « Ce n’est pas

facile pour des familles qui doivent se venger de pardonner parce que,

pendant des siècles, celles qui ne se vengeaient pas étaient jugées

lâches ». Ils ont été aidés par un sentiment largement accepté, selon

lequel les Albanais avaient besoin d’être unis contre le gouvernement

serbe.

Ce sentiment n’a pas survécu au passage au nouveau siècle, ni au départ

des Serbes. Pour Pajazit Nushi, « beaucoup de gens qui s’étaient

réconciliés dans les années 1990, sont à nouveau ennemis et relancent

la vieille querelle d’honneur familial ».

Pour Sadik Dobruna, les membres de la famille Zeneli ne cherchent pas à

se venger à tout prix, si la justice peut être rendue. Mais la mise en

garde demeure quand il ajoute que « si le tribunal se range du côté de

l’officier de police, alors tout peut changer ».

---

ALBANIA:DURO CODICE VENDETTA NON RISPARMIA PACIFICATORE/ANSA

(ANSA) - SCUTARI, 9 AGO - Per oltre dieci anni aveva girato tutto il

nord dell'Albania riconciliando decine di famiglie che, in base al

''Kanun'' - l'antico codice d'onore non scritto che impera nelle zone

di montagna - erano divise da sanguinarie e spietate faide. Ma alla

fine Emin Spahija, 43 anni, capo della Lega dei Missionari di Pace,

sembra sia rimasto vittima dello stesso fenomeno sanguinoso che cercava

di scongiurare: e' stato trovato morto questa mattina nella citta' di

Scutari, ucciso con quattro colpi di pistola. A questo sembrano

condurre gli indizi del delitto. La polizia ha fermato due persone

sospette. I due sono abitanti di Mes, un piccolo villaggio di Scutari,

il paese di origine di Spahija, la cui famiglia pare sia stata da anni

coinvolta in una faida con quella degli assassini, anche se poi

riconciliate fra loro. Gli investigatori escludono i motivi di furto o

rapina, poiche' accanto al corpo del missionario e' stata trovata anche

la sua telecamera e una macchina fotografica, mentre nel portafoglio

c'era ancora una consistente somma di denaro. Non escluse pero' altre

piste legate probabilmente a problemi personali. Oltre ai fermati,

molte altre persone sono state accompagnate e interrogate al

commissariato di Scutari. Ieri sera Spahija aveva partecipato ad una

cerimonia di nozze nella citta' dove si era fermato fino alle 2 del

mattino. Proprio verso quell'ora, mentre lui tornava a casa, sembra sia

stato consumato anche l'attentato, con quattro colpi di arma da fuoco

munita di silenziatore. ''Gli abitanti della zona non hanno sentito

nessun sparo'', hanno spiegato gli investigatori. Il corpo e' stato

trovato casualmente poco dopo le cinque da un passante. All'inizio

degli anno '90 Spahija aveva vissuto chiuso in casa per circa sei mesi,

per paura di una vendetta legata all'omicidio di un concittadino da

parte di un suo cugino. Spahija aveva tentato di persona di mettere

pace fra le due famiglie, riuscendoci con successo poco tempo dopo. Da

quel momento si era dedicato a questa missione. Ed in tutti questi anni

e' stato protagonista di numerosi casi di riconciliazione in diverse

zone del nord del paese. L'assassinio di Spahija si aggiunge ad una

lunga lista di decine di albanesi morti per motivi di vendetta. Un

elenco che non ha risparmiato neppure i bambini, anche se lo stesso

''Kanun'' lo vieta. Tre giorni fa, sempre a Nord, a Rreshen, una donna

di 37 anni, Vitjana Tarazhi, aveva massacrato a colpi di coltello il

nipote di suo marito, un piccolo di 11 anni, Gjoke Tarazhi. La donna

aveva compiuto l'omicidio per vendicare suo fratello, che lei

sospettava fosse stato ucciso dai parenti del marito. Altri bambini

come il piccolo Gjoke vivono rinchiusi nelle case in molte zone del

nord, senza poter andare nemmeno a scuola e con il timore di poter

essere uccisi. Il preoccupante fenomeno ha spinto il ministero

dell'Educazione addirittura a nominare un gruppo di insegnanti che

dovrebbe andare periodicamente a dare lezioni nelle case di questi

bambini. (ANSA). COR-GV

09/08/2004 19:03

http://www.ansa.it/balcani/albania/albania.shtml

=== 2 ===

http://www.iwpr.net/index.pl?archive/bcr3/bcr3_200408_511_5_eng.txt

Desperate Albanians Place Faith in Old-Time Healers

Unable to afford hospital treatment, impoverished villagers are turning

to local magicians for cures.

By Jeton Musliu in Pristina (BCR No 511, 12-Aug-04)

Sinan Hasani, from Terbosh, a village in Macedonia, is happy that he

and his brother have both recently become fathers after several years

of waiting and thank Basri “Hoxhë” Pecani, a white magician, or healer,

for what they call his “gift”.

Infertile couples are not the only ones coming to Pecani, whose title

of Hoxhe suggests he is a Muslim cleric. Among poor villagers in

Kosovo, Macedonia and southern Serbia, healers are doing a roaring

trade as impoverished locals find they cannot afford orthodox medical

treatment.

Unlike the communist era, when medicine was free, Kosovars now have to

pay for their medical services. In cases of serious illness, most

hospitals usually cannot help even when patients have the money, as

they lack modern equipment.

Doctors routinely advise sick patients to seek treatment outside the

country in Turkey or the West – trips that cost far more than most

Kosovars can handle.

Those who come to visit Pecani are not only the sick. Some are

Albanians searching for clues about family members who went missing in

the conflict with the Serbian military in 1998-99, and who turn to

fortune-tellers as their last resort.

Gani, an old man in his nineties, says he turned to Pecani after doing

rounds of hospitals in Pristina, Peja, Skopje and Belgrade, in search

of a cure for his constant headaches and bouts of paralysis. “Now,

after seeing Hoxhe Pecani, I feel much better,” he assured me.

Every Tuesday and Friday people wait in line for hours to get “checked”

in front of Pecani’s two-storey house in Bresje, a village four km from

Pristina. Pecani says his clients not only come from Kosovo but many

surrounding countries too, though the majority are Albanians.

Most people waiting outside the village clinic say they heard about

Pecani’s deeds by word of mouth, though he also relies on

advertisements. Plugs for his services are aired on Radio Dodona, a

local station in Drenas, about 30 km west of Pristina.

But lately, Pecani says his popularity has grown to the point where

even Albanians living in western Europe and the United States come to

visit him.

Though most of his clients are Albanian, Pecani is reluctant to discuss

his own ethnic background. He speaks only poor Albanian.

Pecani bases his ability to cure people on the fact that he once had a

near-death experience. When he was young, he says, he went into a coma

for several days, which he likened to a clinical death.

“The dead heal the living,” is one of his mottos written on the wall in

the small room where he receives his clients.

In this tiny space, which can barely hold three people at a time,

various items are on display, ranging from threads of hair to playing

cards and lights. A tape recorder constantly plays flattering

testimonies from former clients about Pecani and his deeds.

Two loudspeakers in the corridor beam the same messages to the lines of

people waiting outside. Though they all call him Hoxhe, the title is

not strictly accurate, Pecani admits. He says grateful people bestowed

this title on him. But of his reputation as a healer, he is more

bullish, “Don’t trust me - ask the people who come here.”

Local healers have a long tradition among Albanians, as among all

Balkan peoples. Pecani says he had many Serb patients before NATO’s

campaign in 1999 resulted in the flight of most Serbs from Kosovo.

Conservative villagers, few of whom could read, revered healers who

were often the only local people who had mastered a degree of literacy.

They were considered to be closer to God.

Pecani also claims that he can read and understand texts in Arabic that

most Arabic speakers cannot decipher.

Pecani, who says he has been practicing his trade since 1964, insists

his services are entirely legal and known to the authorities.

“Before 1999 I worked with permission from Belgrade - now it is with

permission from Pristina,” he said, pointing at a framed certificate on

the wall published by the Kosovo health ministry and bearing a United

Nations stamp. “This is my work license,” he explained.

In Pristina, the health ministry denies having issued any such

certificate. Skënder Berisha, a ministry spokesman, says his department

would never have released such a document. “No way do we grant licenses

for such things,” he said.

But Pecani stands by his story, claiming he has legitimately obtained

this license and that he is also one of only four people in the Balkans

with the ability to heal people in this way.

Pecani’s certificate is also displayed on the official webpage of the

Office for Business Registration, which operates under the auspices of

the ministry of trade and industry. There, Peçani’s business is listed

as “human health activities”.

When it comes to payment, Pecani says he has no set price, accepting

only voluntary donations.

These do not always come in the form of money. Pecani recalls one time

when a patient brought him a sheep.

“I am a humanist, I am here to serve the people,” he said. “They give

me whatever their heart tells them to give me.”

One Friday, Hata, a 14-year-old Albanian girl from Medvegje, in

southern Serbia, and her father Bislim, came all the way from their

home town to hand Pecani a carefully wrapped present.

Hata said that she had been “possessed” and Pecani had healed her. She

had come back to thank “the living dead man”, as she called him.

“I went to various different doctors but only Hoxhe Pecani found a cure

for me,” Hata insisted, beaming as she handed over her gift to one of

Pecani’s assistants.

Jeton Musliu is a journalist with the Kosovar Albanian daily Epoka e Re.

=== 3 ===

http://www.iwpr.net/index.pl?archive/bcr3/bcr3_200404_494_5_eng.txt

GIRLS FACE PRESSURE TO STOP "WASTING TIME" IN SCHOOL

The advent of political freedom in Kosovo has not freed women from the

widespread notion that serious education is men's business.

By Zana Limani and Driton Maliqi in Pristina and Peja

In the family home in Peja, western Kosovo, 23-year-old Afërdita Gruda

and her older sister Merita spend most of their day at home, doing the

odd bit of housework, watching television and flipping through

Kosovarja, a popular gossipy magazine.

Neither has much chance now of a career, after quitting school on

reaching the end of the elementary level. Both abandoned study under

family pressure. "My grandmother insisted we leave," Afterdita said.

"She said there was nothing for us to learn there."

The sisters' "choice" - such as it was - is all too typical in a

society still governed by most Albanian's conservative moral code,

which tells women their role in life is to perform household chores and

not "waste" time on education.

The result is that after decades of campaigns to improve schooling for

both sexes in Kosovo, there is still no equality between the education

of men and women.

According to Hazbije Krasniqi, of the Womens' Democratic Forum, an NGO

covering women's rights based in Peja, western Kosovo, illiteracy among

women remained high well into the 1990s in remote rural areas such as

Zahaq, a village 7 kilometres east of Peja.

"We found that almost 90 per cent of the women, young as well as old,

had not spent one day in school in their lives," Krasniqi said.

Under the Serbian regime, Albanians were too preoccupied with surviving

Milosevic's repression to give much attention to the matter. But after

the political earthquake of 1999, the Womens' Democratic Forum started

a rural projects in areas like Zahaq, including courses in reading and

writing.

Five years on, however, there remains a mountain to climb. Statistics

show women are far less privileged than men when it comes to education

and according to the Statistical Office of Kosovo, SOK, only about half

Albanian girls aged 15-18 attend school at all.

That alarming figure dovetails with joint findings produced by the

Institute for Development Research, Riinvest, a not-for-profit research

body based in the capital, Prishtina, and the World Bank.

Published on March 31, 2004, this research said only half Kosovo's

women aged 25 to 64 had received even a basic primary education.

By way of contrast, the percentage of girls pursuing higher education

in advanced European societies, such as Sweden and Finland, exceeds 90

per cent.

Hava Balaj, head of the adult learning section in the Ministry of

Education and Technology, says female illiteracy in Kosovo has actually

worsened since the 1990s.

"The number of illiterate women and girls increased during the 1990s

and continued to do so [even] after the end of the NATO bombings," he

said.

The causes of this phenomenon are many, ranging from poverty and

conservative attitudes to such banal factors as lack of transport.

A study in 2001, conducted by Kosovo's education ministry and the UN

Development Fund for Women, UNIFEM, said many of the factors that

contribute to a high "drop-out" level in school-age girls in other

countries are present in Kosovo.

"The reluctance of parents to send girls to distant schools, a lack of

women teachers and lack of financial resources", were among the leading

causes that the report listed.

Hava Balaj, from the ministry of education, says that in rural

communities, when families choose between educating a daughter and a

son, the son always comes first.

"They believe that investing in a son is good value, since he is more

likely to support the whole family with his education when he grows

up," Balaj said.

Balaj added that girls dropped out of higher education in large numbers

in the 1990s after the Serbian authorities effectively expelled

Albanian students from formal schooling from 1991 onwards. Poverty was

another factor.

Although Albanians set up their own parallel structures to counter

state discrimination, their improvised high schools were mostly located

in private houses, relatively far from transport links. This was more

inconvenient for women students than for men.

Since the advent of the UN-led administration in July 1999, new factors

have come to the surface, such as the lack of public transport from

villages to schools. This also affects women more than men. "Women need

public transport because they cannot walk long distances for safety

reasons," said Balaj.

There is also a persistent shortage of staff. Marta Prenkpalaj, head of

Motrat Qiriazi, a local NGO combating illiteracy in the Prizren region

of south-west Kosovo, says the shortage of teachers in rural areas

means teachers either have to come in from urban areas, or schools have

to close.

Prenkpalaj is highly critical of the closure of village schools. "It is

easier for ten teachers to travel to rural parts than for 300 students

to travel a long way to high schools in town centres," he said.

But the problem of women's education in Kosovo is not all to do with

money. Kosovar society is conservative and girls face pressure to marry

early, ruling out any chance of higher education. Motrat Qiriazi says

the average marrying age for girls in villages around Prizren is around

18 or 20.

Those who go on to higher education, and pass this all-important

threshold face the prospect of remaining single for ever.

"Most women in the older generation who finished higher education never

married," said Sanije Vocaj, of Motrat Qiriazi, in Mitrovica.

Unsuprisingly, many girls feel discouraged by this and leave school

early.

In Afërdita's family in Peja, three of her five brothers have gone on

to high school, while she and her sister dropped out.

She hopes that some or all of her brothers will go to university. "I

tell them everyday that they should study hard because school is

important," Aferdita added, wistfully.

"When you are educated you can get a good job, have your own money and

be independent."

Zana Limani and Driton Maliqi are trainee journalists attending a local

IWPR journalism course.

Regressione culturale su tutti i fronti

La guerra di questi anni contro la Jugoslavia e contro il socialismo,

mirata al ristabilimento dell'"ancien regime" nei Balcani, e' stata

accompagnata e sostenuta da una totale regressione culturale. Questo e'

palese in Kosovo e fra gli albanesi come d'altronde anche in tutte le

altre repubbliche ex-federate e tra tutte le altre componenti

nazionalitarie.

1. Sul ritorno della vendetta di sangue ("faide"):

- Résurgence des crimes d’honneur au Kosovo ("Le Courrier des Balkans"

/ IWPR)

- ALBANIA: DURO CODICE VENDETTA NON RISPARMIA PACIFICATORE (ANSA)

2. Sullo sfascio del sistema sanitario ed il risorgere delle

superstizioni:

- DESPERATE ALBANIANS PLACE FAITH IN OLD-TIME HEALERS (Jeton Musliu /

IWPR)

3. Sul massiccio abbandono della scuola dell'obbligo e sul repentino

arretramento della condizione femminile:

- GIRLS FACE PRESSURE TO STOP "WASTING TIME" IN SCHOOL (Zana Limani and

Driton Maliqi / IWPR)

=== 1 ===

( The original text in english:

"Blood Feuds Revive in Unstable Kosovo. Rise in “Honour killings”

blamed on collapse of respect for law and order."

By Fatos Bytyci in Gjakova (BCR No 481, 19-Feb-04)

http://www.iwpr.net/index.pl?archive/bcr3/bcr3_200402_481_4_eng.txt )

http://www.balkans.eu.org/article4117.html

Résurgence des crimes d’honneur au Kosovo

TRADUIT PAR PIERRE DÉRENS

Publié dans la presse : 19 février 2004

Mise en ligne : samedi 21 février 2004

Le nombre des « crimes d’honneur » ne cesse d’augmenter au Kosovo. Dans

les années 1990, une vaste campagne de réconciliation avait été lancée,

mais depuis 1999, la faillite du système judiciaire justifie le recours

à la vendetta traditionnelle.

Par Fatos Bytyci

Il n’y a aucun signe de vie à l’extérieur de la maison des Murati, dans

le village de Duzhnje, au sud-ouest du Kosovo. Les fenêtres sont

fermées et il n’y a pas de traces de pas dans la neige devant la maison.

Osman Murati, soixante ans, n’ouvre le portail central que pour sortir

la tête et voir qui frappe. Il a peur que des gens ne viennent lui

tirer dessus, pour venger le double crime que vient de commettre Valon,

son fils de 20 ans.

Les crimes d’honneur sont profondément enracinés dans la culture

albanaise et ont été formellement reconnus dans la collection des lois

tribales du Moyen Age, connue sous le nom du Kanun de Lekë Dukagjini.

Ce dernier précise que « si un homme en tue un autre, il faut qu’un

autre homme de la famille de la victime, rende la pareille ».

Sous l’ère communiste, les crimes de sang étaient relativement rares

chez les Albanais du Kosovo ou d’Albanie. Mais après les temps troublés

des années 1990, les principes du kanun de Lekë sont réapparus, d’abord

dans le chaos de l’Albanie post-communiste, puis dans le Kosovo voisin,

surtout après les frappes de l’OTAN et le retrait des forces serbes.

Pendant plus de trois mois, ni Valon Murati, ni son frère, son père et

son grand-père n’ont bougé de chez eux, par peur de la vendetta.

Les assassinats ont eu lieu le 10 novembre quand Valon Murati, membre

de la police du Kosovo (KPS) à Gjakova (Djakovica), a tué Sadik et

Safedin Zeneli, âgés respectivement de 55 et 30 ans, en rentrant chez

lui. Les victimes étaient cousins de Valon et venaient du même village.

Isak Zeneli a entendu les coups de feu. « J’ai vu deux personnes

allongées par terre », se souvient-il. « Valon courait vers le village

en criant : J’ai tué deux personnes ».

En attendant son procès, Valon Murati a été libéré sous caution. La

famille Zeneli est furieuse et croit que l’assassin a été relâché parce

qu’il s’agissait d’un officier du KPS. Maintenant ils menacent de se

faire justice eux-mêmes. Sadik Dobruna, leur avocat, affirme que le

tribunal a agi sans raison. « Cette décision a mis le suspect en

danger. Elle lui fera plus de mal que de bien ».

Faillite de la justice

Xhafer Zeneli, le frère de Sadik, n’a pas écarté la menace que la

famille ne prenne sa revanche sur Valon Murati. « Il n’y a pas de

justice au Kosovo. Il a tué mon frère et il est libre. Sadik a beaucoup

de fils en Allemagne. À leur retour, ils se vengeront ».

Selon le canon de Lekë Dukagjini, il faut qu’un meurtrier demande sa

sécurité à la famille de la victime - qui doit donner sa parole, sa «

besa » - pour ne pas être abattu en sortant de chez lui.

Dans le cas des Murati, la famille des morts a refusé de se plier à ce

code, laissant ainsi les hommes de la famille Murati se demander s’ils

n’allaient pas être les victimes d’une vendetta.